Martha Munguia, a graduate student studying Spanish, moved to the U.S. from Mexico when she was 12 years old. Now, 19 years later, she said the political process is still unnecessarily complicated and hard to understand.

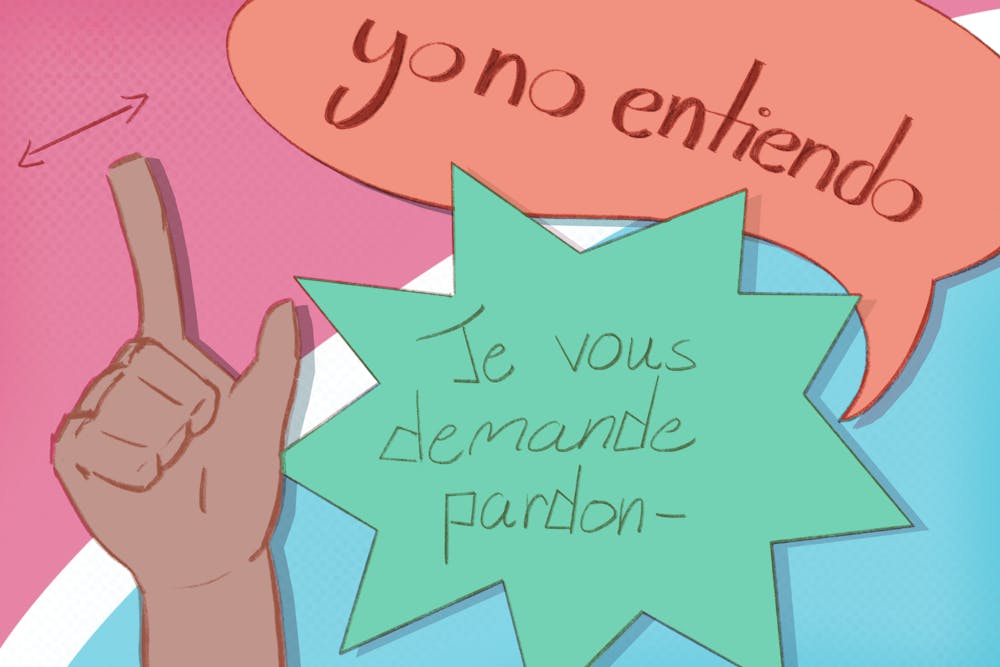

While Munguia is fluent in English, several members of her family are not. Though they are citizens and eligible to vote, her family and families across the country encounter language barriers when engaging in politics.

This is especially true in Arizona, which has one of the largest Native American populations in the country and a combined Hispanic and Latino population of just under 31%, according to World Population Review.

With less language accessibility and diverse representation dwindling, language barriers can discourage people from participating in politics. However, through community outreach and government action, this could start to change.

For Munguia, one of the most challenging parts of the political process is how information is presented.

"There's such a barrier, not only with the language but also how everything's worded, (such as) the language or type of wording in propositions," she said.

She has seen this in newspapers, political advertisements and even voting ballots, rendering it difficult or overwhelming for people who speak different languages to receive their information.

Colette Jung, a professor at the School of Applied Sciences and Arts, said this is often because of a difference between literal translations and their connotations, which might be missed if information is only in written form.

Jung said that translation errors and a lack of accessibility often prompt her students to have to translate for their parents.

"While it's something that they see as important and something that they are just really happy to do, of course, it's kind of exhausting," Jung said.

Munguia said her mother is not fluent in English and her father is not very comfortable with the language, so she often has to translate for them, which could make the voting and political process feel more uncomfortable or embarrassing for them.

Allison Neswood, a staff attorney at the Native American Rights Fund, said this can discourage senior citizens from interacting with politics, which can then disrupt how the rest of the community engages with voting.

"If they're not able to vote, it not only impacts their ability to express their voice in democracy but sends a message to the rest of the community as well that voting isn't for Native people," Neswood said.

Section 203 of the Voting Rights Act dictates that certain jurisdictions must provide assistance for voters who speak different languages. Arizona has 10 of these areas, including Maricopa County.

Neswood said many counties may provide a bilingual poll worker or do radio announcements in different languages, but she still believes this is not enough nor does it meet the act's requirements.

She also pointed out that it is difficult to make political and voting information available in Native American languages because they are not always traditionally written.

While Section 203 offers oral translations for "unwritten languages," Neswood believes they should also have "written guides" of concepts for interpreters to hand out to voters, so they could better understand words like "abortion" or "ranked voting."

Because of the challenges that language barriers and inadequate accessibility create, Neswood said that communities like hers could begin to feel culturally ostracized.

Neswood's family is Navajo. She said that her grandmother was taken to a boarding school where she was punished for speaking the Navajo language and practicing her religion, making her "afraid to teach her kids and her grandkids our language."

"If our elections really embrace Native languages, that can really do a lot to say that Native people are a welcome part of our democracy, or an important part of our democracy, and can be a way to start healing from all of the work that this country has done to diminish and destroy Native language and Native culture," Neswood said.

For Munguia, people who speak different languages might also avoid political involvement because "it is hard for them to be positive or to find that community and have the right connection."

Currently, the state is required to provide bilingual information for languages that over 5% of the population, or 10,000 people within a community, speak. This comes in the form of translated ballots, social media posts and websites, as well as individual assistance for mail-in ballots if a language is spoken less commonly.

READ MORE: Native American voters receive assistance from community advocates

Neswood and Jung suggested there should also be training videos on how to register for voting or how to submit a ballot. Munguia said that on-call centers at polling locations could be helpful too.

But in the end, Neswood said that "voting is only part of any struggle."

"A lot of the struggle is in organizing and strategic advocacy," Neswood said.

Both Jung and Munguia said that one of the most important ways to overcome language barriers in politics is with community outreach.

Jung said that especially for languages that do not have enough of a presence in Arizona to meet language assistance requirements, local organizations like the Palabras Bilingual Bookstore would be the most effective method of spreading translated information or helping people to engage in politics.

Munguia is also focused on how community outreach programs could work on University campuses. She is the vice president of Sigma Delta Pi, a Spanish honors society that is dedicated to sharing Hispanic culture with students across the University.

"I find that there is a connection between having cultural awareness by students from different backgrounds and how they feel about the people that surround them," Munguia said.

"It's important for all voices to be heard, most especially in ... a state that belongs to a nation that is supposed to be democratic," Jung said.

Edited by George Headley, Abigail Beck and Natalia Jarrett.

Reach the reporter at pkfung@asu.edu and follow @FungPippa on X.

Like The State Press on Facebook and follow @statepress on X.

Pippa is a sophomore studying journalism and mass communication with minors in political science and German. This is her third semester with The State Press. She has also worked at Blaze Radio and the Los Alamos National Lab.