New research is being conducted to explore how engineers understand and navigate ethics on a day-to-day basis, prompting questions about how ethics education can be improved.

Engineering disasters are often the focus of traditional ethics instruction, according to Michael Loui, a Professor Emeritus of electrical and computer engineering at the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign, who visited ASU on Nov. 12 to discuss his current ethics research.

While the importance of learning from these tragedies is indisputable, these high-profile mistakes do not entirely address the ethical dilemmas of the engineering field.

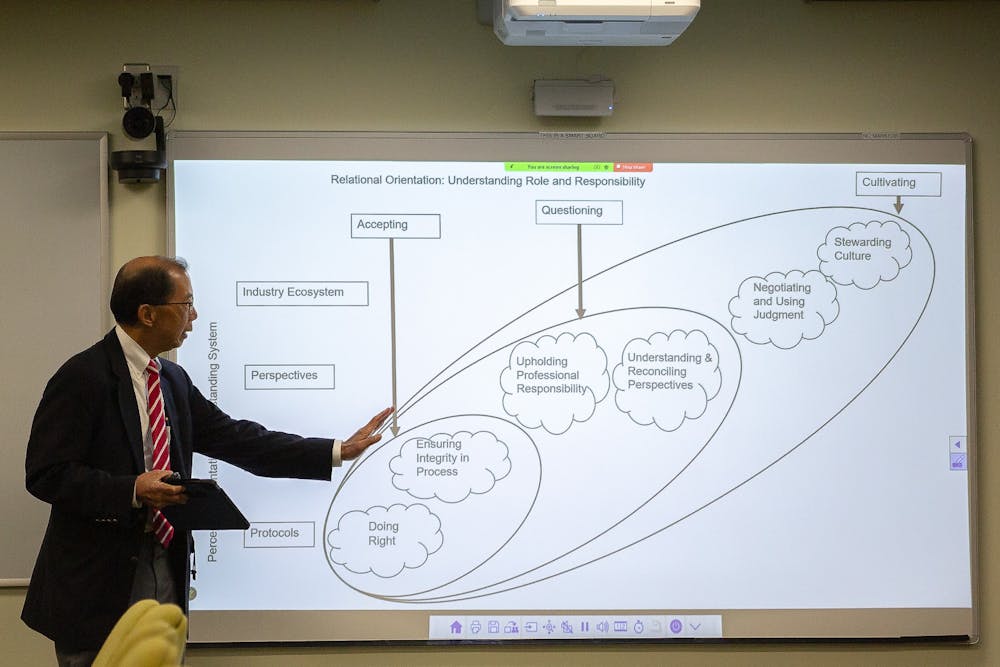

"Engineering ethics in the real world is actually collaborative to figure out the right thing to do. Often it requires talking with other engineers or negotiating through conflicting values," Loui said.

This collaborative perspective in engineering ethics highlights the complexity of the profession.

Jameson Wetmore, an associate professor in the School for the Future of Innovation in Society at ASU and co-director of the Center for Engagement and Training in Science and Society, further emphasized engineers' broad responsibilities.

"(Engineering) is actually a profession, and when it comes to professions, we allow people to have special expertise and extra ability to shape our world in exchange for the promise that they will do it in the best interest of all people," said Wetmore. "There's a sort of a mistaken belief now that engineers work for corporations, and officially they don't. If you're a professional engineer, you work for the people of the country you live in or (work in)."

Despite immense responsibilities, many engineering education programs still lack ethics training. At ASU, there is a one credit-hour course about ethics required for biomedical engineering students, which will take on more credit hours in the 2024-2025 academic year.

The Schools of Engineering serves roughly 30,000 students with only one required ethics course that goes to "I don't know, 2% of those students," Wetmore said. "The biomedical engineering ethics course is in the process of being expanded to three credit hours, so we are beginning to increase the importance of it."

Currently, there are no required ethics courses for students studying mechanical, chemical or electrical engineering at ASU. Instead, they are sometimes offered as optional humanities elective credits. A lack of ethics training courses is not the only concern; how it is taught and incorporated into courses is also equally critical.

According to Caiti Downs, a junior studying materials science and engineering at ASU, ethics should be a mandatory part of engineering courses, but she noted that ethics did not necessarily need to be a standalone course.

"It could be addressed within the curriculum of another engineering course, or perhaps be offered as a Session A/B condensed option," Downs said in an email. "I suppose that might depend on what all subject matter would be covered under the topic."

The effectiveness of various methods of teaching engineering ethics is an ongoing debate. Universities choose different ways to incorporate ethics into their courses, aiming to satisfy accreditation requirements.

"Probably the largest requirement was at Texas A&M University, where a full three-credit course, a standard course on engineering ethics, was required for all engineering undergraduates," Loui said.

The specific content taught in these courses varies and according to Wetmore, ethics is often oversimplified to not lying, cheating or stealing. Even though these are the first fundamental obligations of engineers, they should not be the focus of higher education courses.

"(Not lying, cheating or stealing) makes somebody a basic good human being. And I'm not really sure that's what we need to be teaching at the college level," Wetmore said. "I think what we need to be teaching at the college level are the skills that people need to see ethics where they might not initially see ethics."

Regarding skills, Loui said sympathizing, negotiating and collaborating are essential. These are also general life skills that can be developed through ethics practices.

Drawing from his own experience, Loui linked ethics problems to engineering design problems for his own students.

"When I teach ethics to engineering students, I explain that ethics problems resemble engineering design problems: there are many possible solutions, and some are better than others," Loui said in an email after his visit.

For example, he brought up a time when a new bike lane installation would require 30 trees to be removed. As a solution, 30 new trees were planted elsewhere.

"In short, the best way to resolve an ethical problem is to find a creative solution that honors all relevant values."

With the rapid pace of technological development and social change, ethics have become more and more complex. Having ethical reasoning, particularly negotiating through conflicting values, will ultimately be essential for engineers to make informed decisions.

Edited by River Graziano, Sophia Braccio and Alexis Heichman.

Reach the reporter at hhuynh18@asu.edu.

Like The State Press on Facebook and follow @statepress on X.

Nhi is a freshman studying health care coordination. This is her second semester with The State Press. She has also worked as a content creator.