The internet is a universe of its own, home to infinite galaxies of information strange and familiar to the common user. Our mobile devices are the machines we use to navigate these uncharted territories at light speed — or however long it takes for a page to load.

While most of our online interactions seem to be jumbled patterns of finger touches, swipes and double taps, these miniscule contacts are enough to immerse you in a whole other world, or worlds.

These worlds are more commonly known as fandoms: communities of people who are passionate about certain media, such as a film, a band, a television show or book. Fandoms can be found anywhere and be focused on anything, as long as they gather a strong fanbase.

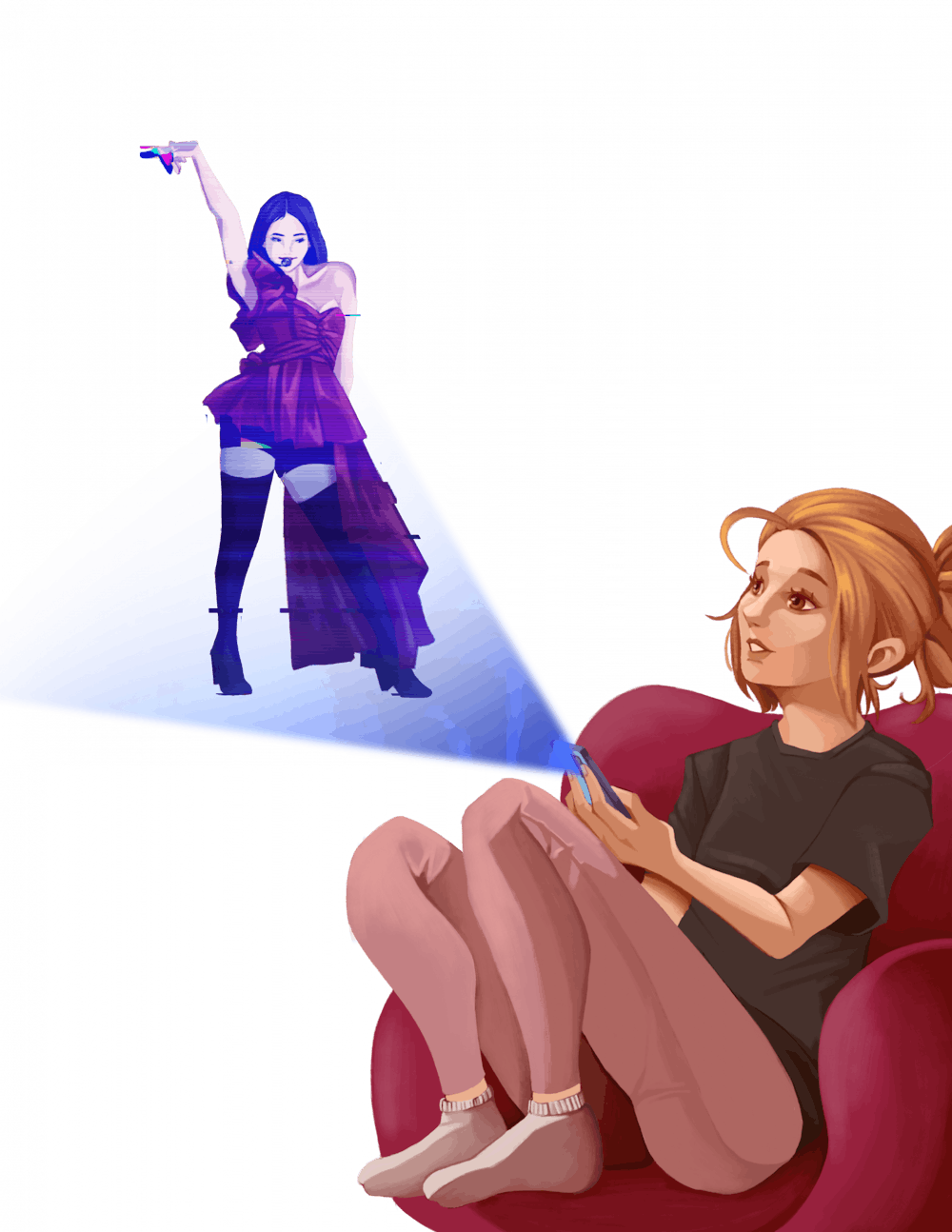

Social media has enabled widespread growth of various accounts dedicated to being a part of these fandoms, where die-hard fans create and circulate edits and photos of their favorite celebrities or fictional characters. Running these accounts can become full-time jobs: constant updates must be made to maintain relevance and engagement.

One Charli XCX Twitter fan account, which currently sits at 55,000 followers, prides itself on being the singer’s “ultimate source.” The admin for the account spoke to the magazine i-D in 2019 when it had a smaller following; they talked about searching multiple online platforms “at least ten times throughout the day” to find any updates on the star.

Some of the most influential accounts, however, have been shut down by social media platforms when they become especially popular. The Beyoncé fan account @Beyhive was shut down by Instagram with 1.2 million followers; a Selena Gomez fan account with over 600,000 followers was shut down due to "copyright infringement" of paparazzi photos.

Instagram has been known for deleting many of these stan accounts on the grounds of impersonation, despite some celebrities leaving likes or comments of appreciation for their hardcore stans. While these are certainly the more popular examples of fandom interactions online, these high-profile pop stan accounts are only the surface of where these communities burrow.

History of fandoms

For years, young women have found solace in fandoms. Whether it be through fanfiction — stories involving fictional characters or fictional stories about celebrities, usually embedding the reader in the narrative — or by running shops on Etsy specializing in fan-made merchandise, women continue to help various fandoms grow around the globe.

Some of the creative property of dedicated fans has evolved into mainstream television and movies. The “Fifty Shades of Grey” series was originally written as a “Twilight” fanfiction called “Masters of the Universe.” The young adult series “Mortal Instruments” has its roots in Harry Potter fanfiction, which author Cassandra Clare originally developed under the title “The Draco Trilogy."

Most notoriously, however, the somewhat poorly executed “After” series by Anna Todd grew popular on Wattpad as a Harry Styles fanfiction, where Styles and a young college student fall in love. So far, the five-part series has been made into four movies, as fans continue to reread the series in anticipation of upcoming films.

These instances in fandom culture blur the line between fiction and reality, as many of peoples’ well-loved stories come to life off the page or the big screen.

The Directioners

“I’ve seen Harry in concert. I have a tote bag from the tour, One Direction merch that I’ve bought from Etsy and I also have tickets to see Louis [Tomlinson] this coming year,” said freshman secondary education student Arlette Fierro. “I was a fan of them in 2015 right before they broke up, and even though they weren’t a band anymore I continued to support them.”

Fierro, who attended Harry Styles’ Love On Tour show in Glendale in 2021, recalled wanting to see the celebrity under any circumstances. “That was my first and only time seeing him, and I bought nosebleeds for $75 at the very top.”

Styles began Love on Tour in September 2021, and has continued to work through several legs of his 22-month global journey, expected to end this July. Fans have been known to spend thousands of dollars to ensure they snag a spot in Styles’ enviable standing-room-only pit section, pressed up against the stage.

“I do take money into consideration, especially as a college student,” said Briana Abate, a freshman studying psychology. “But there’s this quote I see all the time that says: 'Money is fake, Harry Styles is forever.' I’d say I live by that.”

Over the years, Abate has seen Styles in concert on two occasions: once in October 2021 at a show in Florida, and another time at his “one-night-only” concert in New York for his most recent album “Harry’s House.”

“If any of the other boys plan to go on tour, then I’d probably buy tickets for them, too. And Harry’s touring constantly, so I usually follow him around,” Abate said.

Making new friends in Abate’s time at ASU is easy, thanks to her love for the band.

“I connect a lot through the Harry Styles and One Direction fandoms, not just online, but coming into college as a freshman,” Abate said. “Telling people right off the bat that you love concerts or a certain artist, there’s an automatic connection.”

“During quarantine when they had their 10-year anniversary as a band, I joined a group chat with fans that I’m still friends with today,” Fierro said. “We keep in contact and like each other’s posts. I feel comfortable with these people, and knowing these people creates a safe space.”

Fierro said One Direction’s music is something that calms her down and uplifts her mood. “I like the way Harry puts himself out there,” she said. “I know he tours a lot, so it’s nice to see content and know they’re all doing well.”

Although the One Direction fandom has given Fierro long-term connections with other fans, she acknowledges certain fans can sometimes ruin the fun.

“There’s a term in the fandom called ‘solo Harries,’ who are newer fans that really only care about Harry,” Fierro said. “They’ll tear down all the other members of One Direction just because they only like Harry, and usually those people tend to make it difficult to enjoy being a part of the fandom.”

In the idolization of stars like Harry Styles, toxic behaviors in the One Direction fandom have emerged as a result of feuding between stans. “I don’t want to call them ‘crazy,’ but the people that don’t respect boundaries don’t realize the artists are people, too,” Abate said. “I feel like it gives other people that ‘look,’ like all fans are crazy and obsessive.”

“I definitely think they put him on a pedestal and try to act like they’re personal friends with him,” Fierro said. “I know there are people who buy pit tickets to every single show, and it’s those kinds of people who think they’re the better fans because they’ve seen him so many times.”

“I think it’s important to separate the fanbase from the artist because they don’t have control over what their fanbase does,” she added. “Some people are just horrible human beings.”

The A.R.M.Y.

“About eight years ago I discovered them on Youtube, and then I explored their music and music videos,” said BTS fan Nikita Anand. “Stan Twitter was a really big thing, too, around 2017.”

Anand, a junior studying business law, has been a fan of the K-pop genre since it first started gaining mainstream traction in the U.S. “In K-pop there’s something called ‘Vlive’ where idols can livestream and fans can interact with them, so I’d watch,” Anand said. “Besides that, I followed them on everything they had, like Instagram and Twitter.”

Anand, who is currently a dance instructor for ASU’s K-pop Dance Evolution club, saw BTS in 2016 at a K-pop event. “KCON is a really big K-pop convention that happens in LA and New York. I went to the LA one, and there were a lot of other big name artists like SHINee and Girls’ Generation,” Anand said. “In 2018, BTS came back for another concert, but because they’ve become so popular now it’s been really hard to get tickets to their concerts, so I just kind of gave up.”

While groups within the K-pop genre are becoming more mainstream abroad, Anand continues to support them by watching concert highlights online and interacting with social media posts.

Anand owes her transformation as a fan to those she met online: “I was very closeted about my interest in K-pop,” Anand said. “I didn’t want to be stereotyped in a bad way and didn’t want people to be rude by making assumptions.”

Because of her Twitter presence, Anand found a sense of community. “In 2016 to 2019, Twitter was really big. I made a lot of online friends and a lot of them I’ve been friends with for six or seven years now,” Anand said. “K-pop in general has become a safe space for people like me who have similar interests and explore new things together.”

“My sister was a fan of K-pop back in the day,” said ASU alumna Olivia Munson. “In the past 13 years since then, I was a casual listener until BTS came to the forefront in 2016 or 2017, making K-pop more accessible to an American audience.”

Munson “grew” with the A.R.M.Y. fandom, alongside other K-pop groups who debuted around the same time. “It’s been a long-haul with K-pop,” Munson said. “But I’m not an active stan Twitter user. I never have been and I never will be. I’ve never been a fan account girl.”

Munson, a former Barrett student, decided to do her honors thesis on the inner workings of the K-pop fandom, as it piqued her interest. “I knew a girl who did hers on meet and greet culture,” Munson said. “So I wanted to take something I was interested in, too, and expand on it.”

Although Munson was unfamiliar with the K-pop fandom in terms of online congregation, she viewed her thesis as an opportunity to dissect further into the parasocial nature between A.R.M.Y. stans and K-pop celebrities.

“During the height of the pandemic, there were these messaging apps that fans could pay for to communicate with idols. You were put into group chats with idols who could message you throughout the day,” Munson said. “I talked about how that constant communication fosters parasocial relationships and brings fans back for more.”

Munson said these relationships are responsible for keeping these fandoms relevant. “What we see in any fandom is high saturation of content. When there isn’t content to consume is when people tend to fall to the wayside. K-pop thrives on parasocial relationships,” Munson said.

A broader look at parasocial relationships

“I grew up in the ‘80s with ‘The Cosby Show’ and ‘Family Ties,’ and it was interesting to me even back then how I saw people on the screen and liked them,” said Alden Weight, an assistant teaching professor for the Polytechnic social science program. “They seemed like friends and cool people I might like to know.”

Weight has worked at ASU for 17 years and has previously studied the nature of parasocial relationships with fictional characters and celebrities. “People can take advantage of parasocial relationships too, and capitalize on them. Many scholars will argue that a successful book will be able to create an identifiable character that people will just love.”

While this gives insight into some of the strategies used by TV and creative writers to engage with fandoms on a level that rakes in profit, Weight shared the reality of attachments to celebrities from an online standpoint. “You’re seeing who the celebrity has chosen to project,” Weight said. “It’s basically a PR exercise.”

In terms of our interactions with celebrities on social media platforms, Weight believes we are all guilty of fabricating our personas on the web. “This isn’t something exclusive to celebrities. We all do impression management,” Weight said. “But you would be seeing a parasocial relationship with the way celebrities present themselves on social media.”

When asked about the potential danger in these relationships, Weight shared how they could negatively impact what we decipher to be true online. “The potential is always there,” Weight said. “If somebody becomes attracted to that persona, they don’t know the whole picture. They could commit any number of strange errors.”

According to Weight, humans are instinctively drawn toward building these types of bonds. “We all have the propensity to develop them. We’re social creatures. We’re hard-wired for connection with other people. As the saying goes: ‘It’s in our DNA’ to want to develop relationships with other people,” said Weight. “And it’s so intriguing because you are only attracted to part of that celebrity’s personality.”

Editor’s note: Olivia Munson worked for The State Press from 2019 to 2022.

This story is part of The Spectrum Issue, which was released on April 5, 2023. See the entire publication here.

Reach the reporter at lmesqui2@asu.edu and follow @leahmesquitaa on Twitter.

Like State Press Magazine on Facebook, follow @statepressmag on Twitter and Instagram and read our releases on Issuu.