In 1991, the Soviet Union was on its final leg. A military coup threatened to overthrow Mikhail Gorbachev's government and tanks rolled down the streets of Moscow as protesters erected barricades at the Russian parliament building.

Geochemistry is the study of geological systems and other planets through chemistry principles. Geochemists apply their knowledge to analyze the composition of planets and make theories about the makeup of celestial bodies and how they were formed.

Galina joked with Zolotov, telling him geochemists were smarter than geologists but not as smart as chemists, Zolotov said.

"I was comfortable (studying geochemistry). It was the right decision because anxiety stinks," Zolotov said. "Geologists think I'm a chemist, and chemists think, 'Oh, Misha (his nickname) is a geologist.'"

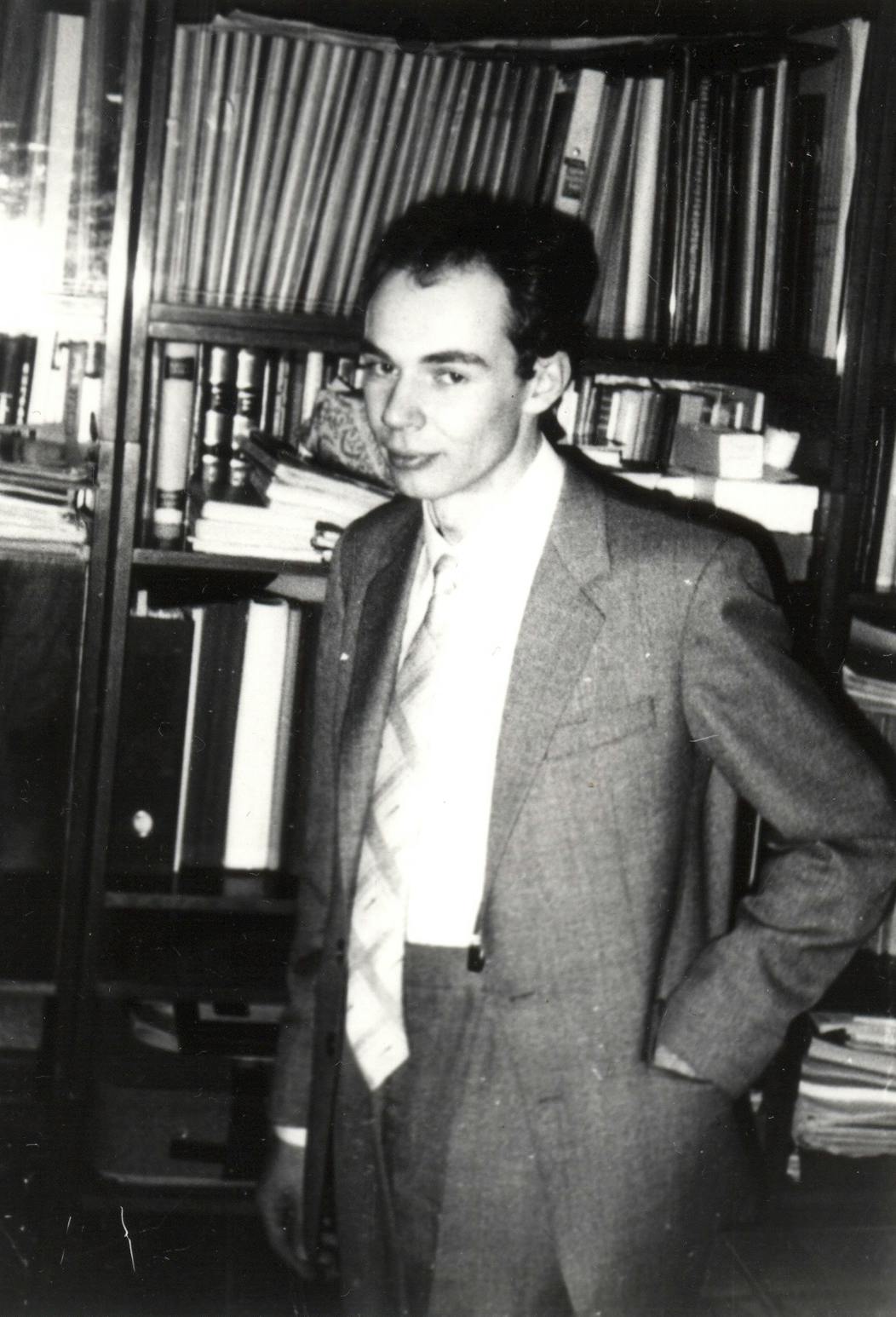

Zolotov attended Moscow State University and graduated in 1982 with a diploma in geology and geochemistry. Afterward, Zolotov continued to study and work at the Vernadsky Institute where he received a candidate of science, the equivalent of a doctoral degree.

Using his knowledge of geochemistry and thermodynamics, Zolotov published research papers about the composition of the surfaces of Mars and Venus.

Bruce Fegley Jr., a professor at Washington University in St. Louis, said Zolotov is one of the few people in the world "who knows how to apply thermodynamics to planetary science and to meteorites."

Zolotov still passionately studies Venus. He is a co-investigator for Deep Atmosphere Venus Investigation of Noble gases, Chemistry, and Imaging, a NASA-sponsored space probe that will measure the composition of Venus’s atmosphere.

Venus, with its hot and highly toxic atmosphere caused by rampant greenhouse gas, might reflect Earth's future, Zolotov said. However, Zolotov is not worried about Earth becoming like our sister planet. To him, it is the natural order of things.

"We all die eventually, it's the same story with the stars," Zolotov said.

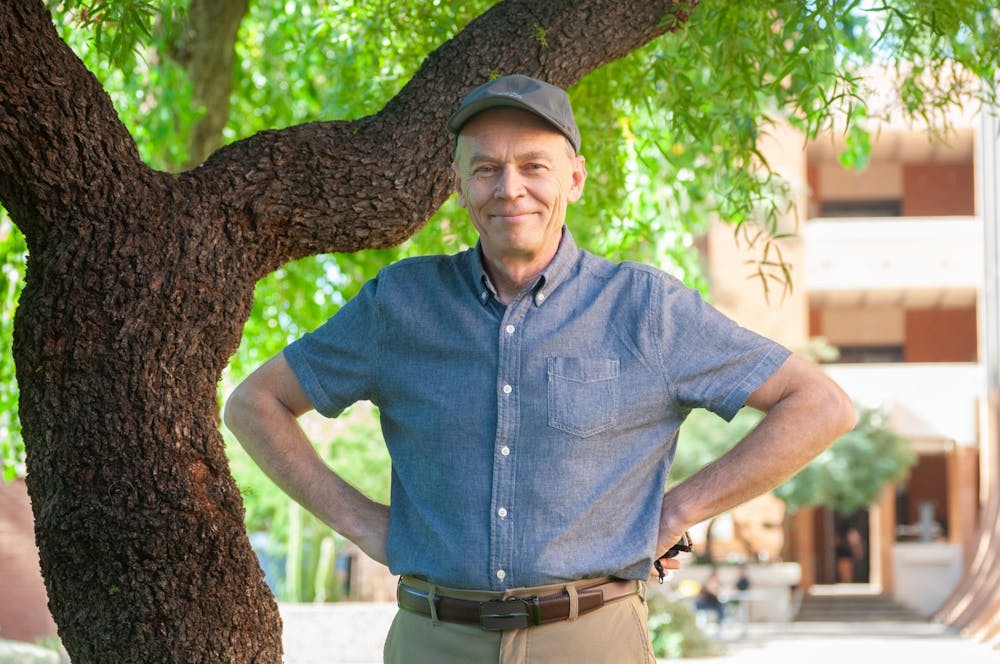

During his time at the Vernadsky Institute, Zolotov was in contact with American scientists. Ronald Greeley, the planetary scientist whose name adorns the Ronald Greeley Center for Planetary Studies, invited Zolotov to come to ASU after meeting him at a conference in Moscow.

READ MORE: How ASU fell into NASA's orbit

Despite political tension, scientific communities in the U.S. and Soviet Union worked together even during the height of the Cold War, according to Fegley.

"Scientific exchanges had existed between the U.S. and Russia about Venus going back into the 1960s, so this was just something normal at the time," he said.

On his first visit to the U.S. in January 1989, Zolotov came to Arizona and visited the Department of Geology, now part of ASU's School of Earth and Space Exploration.

"I was so excited because it was January, and January is beautiful, and I see all the orange trees and beautiful architecture," Zolotov said. "Compared with January in Moscow, which is dark all the time."

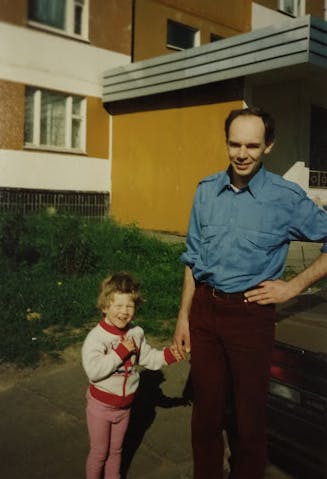

Zolotov made several other visits to the U.S. before moving with his family to St. Louis in 1996 to work with Fegley who gave Zolotov financial support through grant money for a year.

Fegley and Zolotov published papers about volcanoes on Io, one of Jupiter's moons, predicting sodium chloride vapor would be seen in volcanic gasses on Io, a fact later proved by spacecraft observations, Fegley said.

During his research with Fegley, Zolotov was not making enough money to live in the U.S. In the fall of 1997, Zolotov said he almost had to return to Russia.

However, an opportunity presented itself when Everett Shock, a professor at ASU, hired Zolotov to help him study Mars, Zolotov said.

Zolotov has been working with ASU students since the early 2000s, and started publishing papers about Europa, an icy moon orbiting Jupiter many believe could harbor life.

Christopher Glein, an ASU alumni and senior research scientist at the Southwest Research Institute, works with Zolotov on the Europa Clipper, a spacecraft that will study its makeup.

"It's not all just about finding aliens," Glein said. "It's also about understanding new places, what those places are like and how they got to be that way."

Every year or two, Zolotov writes a study that advances the planetary science field, and his work is always driven by the fundamentals, Glein said.

"I would say he's more intense than 99% of people who review work," Glein said. "He's very rigorous in how he does science."

Despite his contributions to science and unique history, Zolotov couldn't care less about recognition, his concern lies in hard work and reputation.

"I think the reputation is much more important than the formal status stuff," Zolotov said. "Eventually people will remember you by what you did, but not what was your records, (like) how many medals you had."

Correction: A previous version of this article incorrectly stated the institution Galina taught at as well as Zolotov’s involvement with ASU in the early 2000s. This article was updated at 6 p.m. on Feb. 17, 2022, to reflect the changes.

Reach the reporter at kryback1@asu.edu and follow @KadenRyback on Twitter.

Like The State Press on Facebook and follow @statepress on Twitter.

Kaden is a reporter for the Biztech desk, focusing on student run business, people profiles and research papers. During his time at The State Press, Kaden's biggest piece was about ASU's history with NASA. He's a sophomore majoring in Journalism and Mass Communication.