The ASU-developed ShadowCam instrument was successfully shipped to the Korean Aerospace Research Institute (KARI) and incorporated into the Korean Pathfinder Lunar Orbiter (KPLO) spacecraft. The project is set to be the Republic of Korea's first space exploration mission to travel beyond Earth in August 2022.

The KPLO engineering team is now running functional tests on the ShadowCam, a camera that will allow for the precise imaging of shadowed zones on the moon during the mission, to ensure cooperation between it and the rest of the multi-pieced spacecraft. With most of the KPLO assembled, the next steps for KARI are run the necessary tests for space travel and to finish incorporating the group's own instruments into the spacecraft.

Due to COVID-19 restrictions, those involved in creating ShadowCam were unable to travel to South Korea and aid the installation process. Instead, they sent over detailed instructions and conducted a livestream event with the KARI team to provide clarification on the instructions.

"We decided that ... since the engineers at KARI are well-educated and they know how to do something like this, it would be okay," EK, principal researcher for the KPLO, said. "But it was a first step for KARI, so we were a little worried ... We had the documents and the live call for clarification ... so that they could see how KARI engineers worked during the installation process."

Overall, everything went smoothly during installation and ShadowCam has now been completely incorporated into the KPLO, EK said.

ASU's Mark Robinson, the principal investigator of ShadowCam, Prasun Mahanti, research scientist and deputy principal investigator of ShadowCam, and the rest of the ShadowCam team are shifting away from mechanical duties to prepare for the "science side" of the mission. Along with helping KARI with "post-integration support," the ASU team is preparing for what happens when the KPLO is launched and in space, Mahanti said.

"Our main focus has now shifted to what you'd call operations," Mahanti said. "We need to have everything ready. All the software, all the people, all the skillset has to be ready for when it happens."

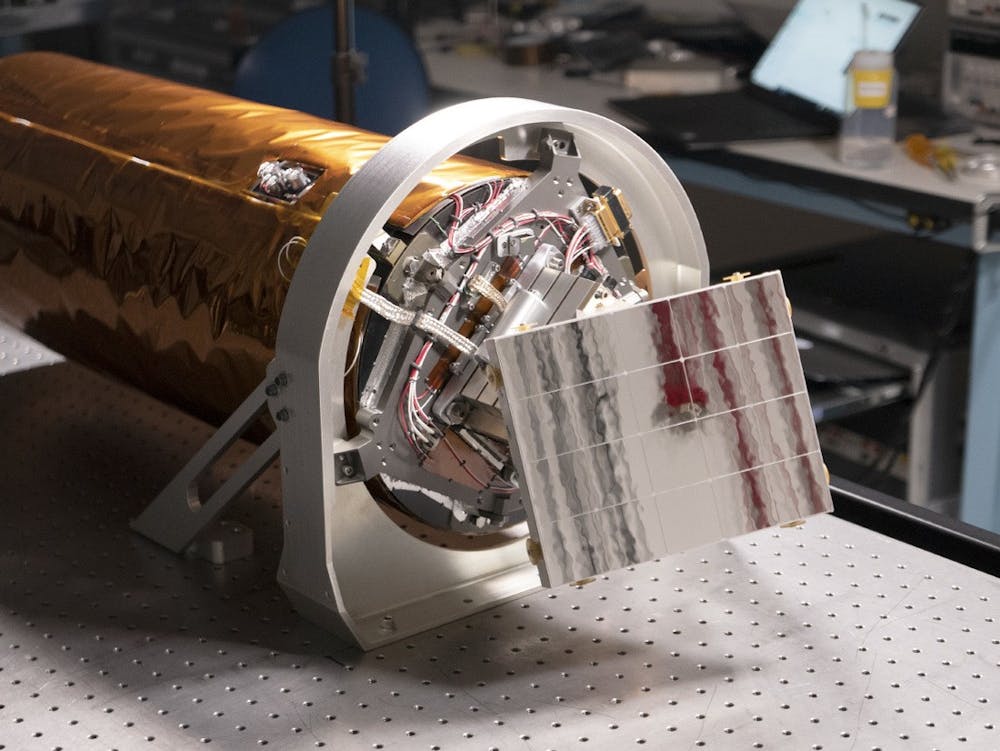

The ShadowCam design was born from the influence of the Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter Camera Narrow Angle Camera (LROC NAC), which has been mapping the lit side of the moon since its launch in 2009.

After the apparent success of LROC NAC, Robinson developed the idea of a camera that could map the regions of the moon that are considered permanently shadowed and determine if volatiles — ice, water, methane and ammonia — reside there.

"You can break (water) down very easily into hydrogen and oxygen using solar power ... that's rocket fuel," Robinson said.

This could essentially make future space travel easier and cheaper. With fuel already on the moon, longer trips in outer space become achievable without the hassle of large fuel tanks on spacecrafts.

In 2017, Robinson, Michael Ravine of Malin Space Science Systems (MSSS) and their team submitted a proposal and were chosen by NASA to incorporate the ShadowCam into the KPLO mission.

While the LROC NAC was originally designed to map the regions of the moon illuminated by the sun, it still has the ability to map shadowed areas, but only relays "poor quality" images, Robinson said.

Given the lack of light and functionality of the NAC aboard the LROC, the instrument isn't able to accurately map the permanently shadowed regions to determine whether they retained volatiles.

Since the approval of their proposal in 2017, Robinson and his team had been creating the ShadowCam and a Time Delay Integration detector housed within it. This detector is 200 times more sensitive and will allow for "high-resolution pictures into much of the permanently shadowed regions," Robinson said.

By utilizing the TDI, a detector that is not part of the LROC NAC, the ShadowCam will have a longer exposure time to use the limited amount of light and scan the shadowed regions of the moon to effectively gather images.

"We'll be about 100 kilometers altitude above the moon, and, as we fly over these craters, we will eventually, over a period of a year, map all the permanently shadowed craters," Robinson said.

Being able to determine if any volatiles lie in the craters could lead to resources for future solar system exploration, Robinson said.

Having worked on the LROC NAC in the past, the construction of the ShadowCam was very familiar to MSSS.

The telescope itself looks the same as the LROC NAC with only minor changes and add-ons that will aid ShadowCam in doing its job, but, ultimately, the biggest change was the integration of the TDI, said Ravine.

"Because it is a completely different detector, that whole section of electronics had to be redesigned completely from scratch so that part was actually different and it took a fair amount of effort," Ravine said.

The goal of the mission remains to simply map the shadowed regions and, from there, determine whether usable volatiles exist within the craters.

The KPLO is scheduled to launch Aug. 1, 2022 at Cape Canaveral on a SpaceX Falcon 9 rocket.

Correction: A previous version of this article misspelled the name of Malin Space Science Systems and incorrectly referred to the TDI as an instrument. The article was updated at 3:00 p.m. on Sept. 29 to reflect the changes.

Reach the reporters at ljchatha@asu.edu and follow @LukeJC2 on Twitter.

Like The State Press on Facebook and follow @statepress on Twitter.

Continue supporting student journalism and donate to The State Press today.

Luke Chatham is a Community & Culture reporter and previous Business and Tech reporter. He also worked in the studio production crew for Cronkite News and is currently a freelance reporter and writer for Arcadia News.