When Rosemarie Dombrowski stood in front of her class and shared a poem about her son, who was diagnosed with autism and three congenital heart defects, it was not just a display of vulnerability with her students — it was an example of poetry used as medicine.

Dombrowski began working at ASU in 2006 and currently serves as a lecturer. She has led multiple classes in women's literature and medical humanities.

But above all, she's a poet.

Dombrowski has integrated her love of poetry into her academic life by practicing the therapeutic benefits of poetry at ASU.

"We all were bawling by the end of it. It was an incredible, a surreal experience," said Danielle Du, a senior studying medical studies who participated in Dombrowski's classes.

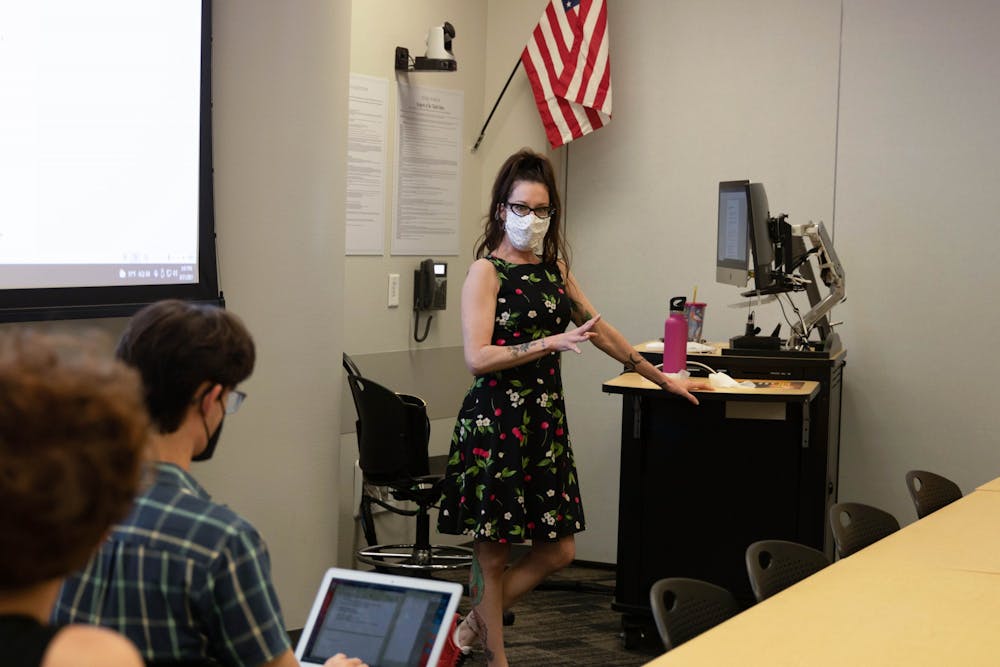

While her poetry can be heart-wrenching, Dombrowski is the antithesis of melancholy. Her students described her as, loud and passionate, a character who's larger than life, and one who has had an impact on the ASU community using her greatest tool: poetry.

Dombrowski is built to retain the attention of a classroom full of tired college students. She acts a living pop-out book of information whose delivery turns a seemingly mundane topic into a learning opportunity. Dombrowski's hands fly with her words, and she is exuberant when given the opportunity to talk about her favorite works by Walt Whitman and Emily Dickinson.

"Nothing I say can prepare you for the reality of what Rosemarie is. You have to experience it," Du said. "She embodies the writing process as she talks, and she connects disparate things together."

In 2016, Dombrowski was appointed the inaugural Poet Laureate for the city of Phoenix. One of Dombrowski's primary tools to help empower community members through poetry is, what she calls, poetic therapy, a process which helps patients confront traumas and physical ailments through poetry.

At Revionsary Arts, a non-profit Dombrowski founded through funds from a fellowship, she teaches therapeutic poetry workshops in the Phoenix area.

Participants gather and open up about their lives. As they finish grappling with their memories and experiences, participants take control of their traumas and the feeling in the room is palpably relaxed.

"The dominant theory behind poetic therapy is that, when we are able to recast that incident, that trauma, that hurt in our own story, we are able to take back a little bit of power," Dombrowski said. "Instead of allowing a diagnosis or a death to dominate our lives, we are able to say, 'In this space today, I'm going to rewrite this story.'"

Barrett students have the opportunity to explore some of Dombrowski's interests in the intersection of the medical and the poetic in her class, Poetry and Medicine.

Dombrowski believes the class "was truly born out of a life's worth of work as a poet," and was an opportunity for her because she was "advocating for medical poetry as a kind of salve for those who might be suffering and feeling isolated."

To present it in a class is a new opportunity.

The first half of the class explores American poets' work like Rafael Campo and Sylvia Plath, who used their poetry as physicians. It also focuses on patient poets who used the art form to explore the depths of their subjective experiences, from the horrors of trenches in World War I, to the pains of breast cancer.

The poetry Dombrowski teaches isn't the cliché poetry people may imagine when thinking of the art. On the contrary, it's a translation of cultural and historical data into poetry, Dombrowski said.

The convergence of these poems in the first weeks of the course "is a really powerful dose of the medicine of poetry. This isn't poetry that speaks to life philosophies; this isn't poetry that speaks to religiosity; this isn't poetry that speaks to an endless vat of hope in the universe. This is poetry that talks about f---ing cancer and f---ing cancer treatment."

Later in the course, students will form small groups and curate therapeutic poetry workshops for ASU partners at the Westward Ho and the Phoenix Biomedical Campus. Students must discover what works best for their audiences and create an environment where writing exercises can lead to a poem others want to share.

Shiv Shah, a junior studying biological sciences and literature studies in Dombrowski's class, did his workshop at the Mirabella at ASU, a retirement community in Tempe. After the experience, Shah walked away with a new appreciation for the power of poetic therapy.

"It was really incredible. They talked about things that they never really talk about. Some of them were veterans. Some of them even were crying about the things they could unravel, just because there was someone with a hand on their back guiding them through their emotions," Shah said. "That sort of experience kind of opened my eyes to the sort of therapies and avenues of care that people who don’t traditionally have medicine can access."

Du led her poetry workshop at the Westward Ho. "The creative responses and the way they talked about their experiences" was so rewarding that she agreed to work with Dombrowski on future workshops.

Dombrowski's life has shaped poetry in her community just as much as poetry has shaped her.

As a caregiver for her medically fragile son, Dombrowski has used poetry to help her deal with the stresses which accompany her life.

"Poetry is my therapy. That's how I became a poetic therapist. If you cannot care for yourself, you cannot care for your patients," she said.

The use of poetic therapy shows in Dombrowski's poetry. When she had her son in graduate school, she stepped foot into the realm of disability and medical culture and has remained there ever since. Dombrowski took the challenges she faced as a caregiver and turned towards artistic expression in her first collection of poetry, "The Book of Emergencies," which was a lyrical description of the culture of autism.

With her array of projects and deep-rooted belief in the benefits of poetry that is applicable to all facets of life, Dombrowski does not sell herself short. She "has always been a creative dreamer."

"My parents let my creative mind run free," Dombrowski said. "I've never been corralled, and so it's very difficult for me to spend years gestating these things, these little projects, these courses, these ideas and then not allow them to explode into something bigger. I think that once we invest ourselves into something we are passionate about, why should we start thinking about the limits of that? There are no limits."

Reach the reporter at kryback1@asu.edu and follow @KadenRyback on Twitter.

Like The State Press on Facebook and follow @statepress on Twitter.

Continue supporting student journalism and donate to The State Press today.

Kaden is a reporter for the Biztech desk, focusing on student run business, people profiles and research papers. During his time at The State Press, Kaden's biggest piece was about ASU's history with NASA. He's a sophomore majoring in Journalism and Mass Communication.