Elizabeth Baer wanted to become a wind musician in an orchestra, her family thought she might attend fashion school and for a long time, she wanted to be an anesthesiologist. But at 17, she joined the military and learned to build bombs.

"I never pictured myself joining," Baer said. But financial hardships at home prevented her from pursuing college and the military appeared as the best detour to higher education.

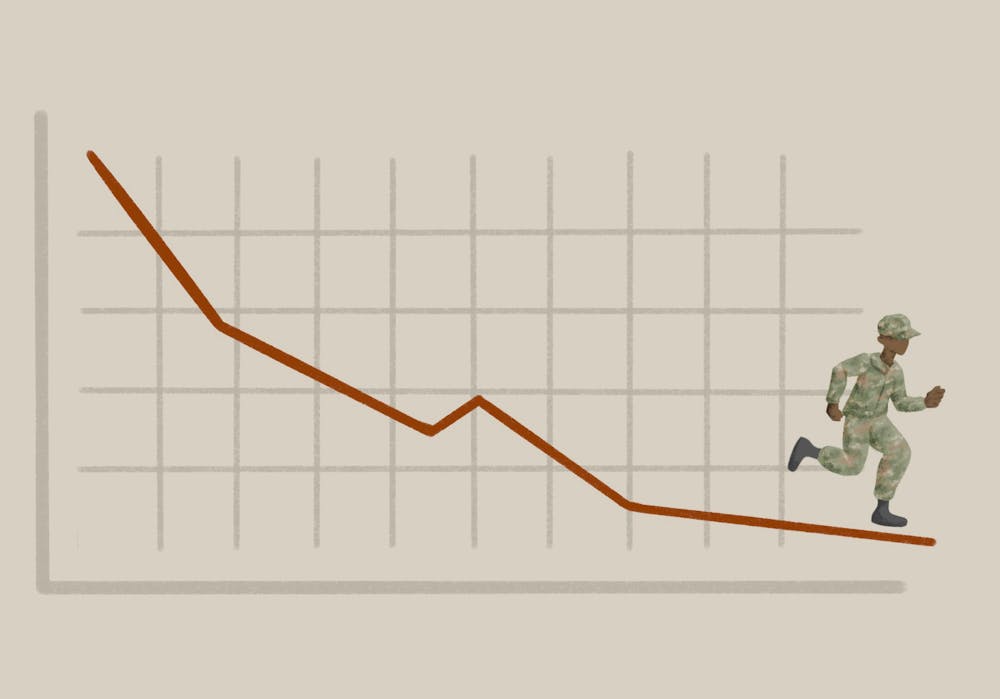

Almost 10 years after Baer opted out of a traditional path to higher education, another economic crisis derailed more than 16 million Americans' plans to go to college. Meanwhile, recruiters for some branches of the military are meeting recruitment goals after a pair of years where goals were missed or significantly lowered, according to Department of Defense statistics.

Beth Asch, a senior economist at the RAND Corporation, released multiple books outlining how military recruitment changed over the latter half of the 20th century to the modern day.

"A lot of people don't have money for college," Asch said. "So the military offers an opportunity to get money for college, which you earn by completing a service obligation."

Recovering from the Great Recession was difficult for Baer's father. He regularly found himself "on the chopping block" at new jobs. And the businesses continued downsizing, Baer said.

As her father sought new jobs to support his family, he brought the Baers on a nomadic search for jobs over the course of four years to Pennsylvania, Illinois, Florida and eventually Australia.

Baer's mother worked for Pennsylvania's State System of Higher Education, which provides dependents of their employees 100% free tuition at any state university. But her mother was forced to leave her Pennsylvania government job to be with her husband in Florida. Baer suddenly realized she didn't "have free school anymore."

The price of college has shot up exponentially in the past 40 years, rising more than 500% since 1982, according to College Choice; more than double the rate of inflation during the same time period. In 2020, U.S. student loan debt reached more than $1.7 trillion.

The debt collectively owed by Americans to college is now the second largest form of debt behind housing, according to Experian, a consumer credit reporting company.

Volunteer forced

"When there's a downturn in the economy, people are not just more likely to join the military, they're also more likely to go to college," Asch said. "There's a certain element of that, where the military is competing with colleges for qualified people."

Nearly 5 million more people are unemployed now than in February last year despite the stock market hitting record highs, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics. And 30 to 40 million Americans are at risk of eviction according to an analysis by the Aspen Institute.

"Where the military comes in, is it's offering me a job — although, of course that's the case — but it's also offering me a future when the future seems uncertain in the civilian world," Asch said.

An April report from the Senate Joint Economic Committee — when there were only 50,000 COVID-19 deaths — stated, "When the pandemic subsides to a degree that Americans can return to some version of their former lives, it likely will leave in its wake even greater inequality."

A significant number of students are choosing to put off college until the storm passes. The National Student Clearinghouse Research Center found a 21.7% decline in high school students entering college during the Fall 2020 semester.

Yet ASU defied that trend by maintaining its on-campus student population and growing its online student population by 19% since last January. Matt Lopez, the associate vice president of enrollment services cited a familiar reason for defying this trend.

"ASU's innovation mindset allowed the University to leverage existing strengths, but also rapidly create new ones to ensure that students have learning options available so their education could continue with minimal disruption," Lopez said.

But going to college was not an option for Baer — at least without a major deviance to her educational path.

As she contemplated entering the civilian workforce, Baer's father gave what he describes as "tough love": She had to figure out her own way to go to college by herself.

"That was a turning point where I just kind of thought to myself, 'How am I going to do this?'" Baer said.

Got you by the bootstraps

In order to achieve her goal of going to college, Baer joined the military at 17 with parental consent. Through the military, she found "a pathway to college" and the job security her father struggled to find while she was a teenager.

But like many young adults today, Baer was dismayed at the idea of going to college without the opportunity to experience the full scope of college life.

"I had this jaded facade of what college would really be like. I imagined myself with my little 'Fjallraven Kanken' bag with my books in my hand," Baer said.

Baer only spent one day on campus due to the pandemic.

This lack of a social aspect to the learning and college environments caused some college students to drop out and join the force, said Capt. Jose Narcia of the Arizona National Guard. Narcia leads the recruitment and retention battalion where he coordinates National Guard recruiting of young men and women in Arizona.

"There's some students that have left college because they didn't really like to remotely go to college," Narcia said. "The second piece is that you see a lot of people who realize how fragile the world can be, and unpredictable at this time."

More than 208,000 Arizonans are unemployed, the most since July 2020, according to the Bureau of Labor. And according to a 2020 Feeding America study, close to 1 in 5 children in Arizona are struggling with food insecurity.

Yet Narcia described that his best National Guard recruiter had told him that of "every single person" he signed up, that "none of them were unemployed."

"What the recruiters typically do is try and figure out whether the Guard are going to be able to help them in their careers, whether it's going to supplement it or complement their career," Narcia said.

The desperation that has gripped millions throughout the country from the COVID-19 and its impact has likely given new resonance to the military's message of economic security, said Baer.

"COVID-19 has given the military one of the largest bargaining chips of the decade," Baer said. "They could definitely say, 'Hey, you're experiencing economic hardship right now? We will feed you, clothe you, and house you.'"

Attempting to sign a person up for the military by pressuring students with all of the benefits or joining the force is called "dumpster loading," Narcia said.

"That's not how a recruiter is going to talk to you," Narcia said. "Normally, when somebody talks about somebody being interested, it's more of, 'Have you ever thought about serving in the military?'"

People are feeling a sense of duty in the past year to join the National Guard and aid in the distribution of COVID-19 tests, food and vaccinations, Narcia said.

But the serving in the military is not without its downsides. Pediatricians and other researchers found that military recruiter's tactics, including who they target, are "disturbingly similar to predatory grooming."

According to a 2011 study in the National Center for Biotechnology Information studying recruitment tactics compared to the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child.

The guidelines of the convention bar military recruiters from subjecting minors to military recruitment. But of all U.N. member countries, only the United States and Somalia have not ratified the convention, the study said.

"Although adults in the active military service are reported to experience increased mental health risk, including stress, substance abuse, and suicide, the youngest soldiers consistently show the worst health effects," the study said.

Rates of alcohol abuse, anxiety disorders, depression, and self-harm were found to be higher in younger soldiers aged 17-24 than older soldiers, according to the study.

The difficulties young veterans face is partly why Baer decided to work at the Pat Tillman Veterans Center to help veterans transition back to civilian life.

And though the military has set up programs to aid in the civilian transition, Baer said, "no matter what they say, you'll never be prepared for that transition."

"That's actually why I applied to help be a part of the veteran's center, because I wanted to help other students get a grasp on what it's like to transition fully to be a civilian," Bear said.

The earring

Baer said her experience is emblematic of common military service pitches: Travel the world, gain valuable work experience, serve your country.

She traveled throughout Europe, embarked on a tour in South Korea, and picked up languages along the way. She excelled as a young woman in the Air Force, ascending through the ranks to sergeant — which gave her the duty of commanding men sometimes a decade her senior.

Going overseas didn't just mean she had to leave her family behind, it also meant that she would have to have her personal life in an ice chest to come back to.

"The guy that I broke up with in high school and now has two kids," Baer said. "And I have four cats."

She reconciles her missed time building a life at home with the "surreal and almost unfathomable" opportunities she's had visiting Morocco in Northern Africa, Petra in Jordan, and seeing the Eiffel Tower at night in Paris, France.

But the surreality of living abroad ended when she returned to the U.S., realizing she would be graduating at 30 years old in May 2022.

"I put seven years aside so that I could serve," Baer said. "At times I felt stagnant in my education and that my life was on hold."

But leaving the military and becoming a citizen again doesn't work like a switch. One person she met in a tax class spent a quarter-century in the military.

"He doesn't know anything else," Baer said.

Baer realized the military mentality had ingrained itself in her when she was looking for houses. She began to panic when she realized she would be 5 minutes late to a realtor's appointment because "if you're not 15 minutes early, you're late" by military standards.

She had to get used to waking up later than 4:30 a.m. But it took a second ear piercing banned by military standards to get it through her head that she was a civilian again.

Wearing a pair of teardrop earrings from her mother and another pair of a sun within a moonstone, she said, "When I got out of the military I got a second piercing. And I thought I was such a rebel."

Reach the reporters at cbudnies@asu.edu and follow @Chase_HunterB on Twitter.

Like State Press Magazine on Facebook and follow @statepressmag on Twitter.

Continue supporting student journalism and donate to The State Press today.