On March 19, a group of students and faculty assembled on the West campus. It split in half and the group traveled from building to building, marking accessible restrooms and elevators found inside.

One group began mapping Fletcher Library. The group took volunteers through the building, pointing out features of an accessible bathroom: 32-inch wide doors and a clear path with accessible buttons on both inside and outside the large stall, grab bars around the toilet, mounted sinks, floor urinals, universal changing tables and easy access for a user under 48 inches tall.

The team also examined the elevators inside Fletcher, Kiva and Sands buildings. David Jaulus, a graduate student in justice studies who uses a wheelchair, tested the space in one elevator near the Kiva building, laughing at the sign that touted an occupancy limit of four people. His wheelchair took up all of the elevator's floor space.

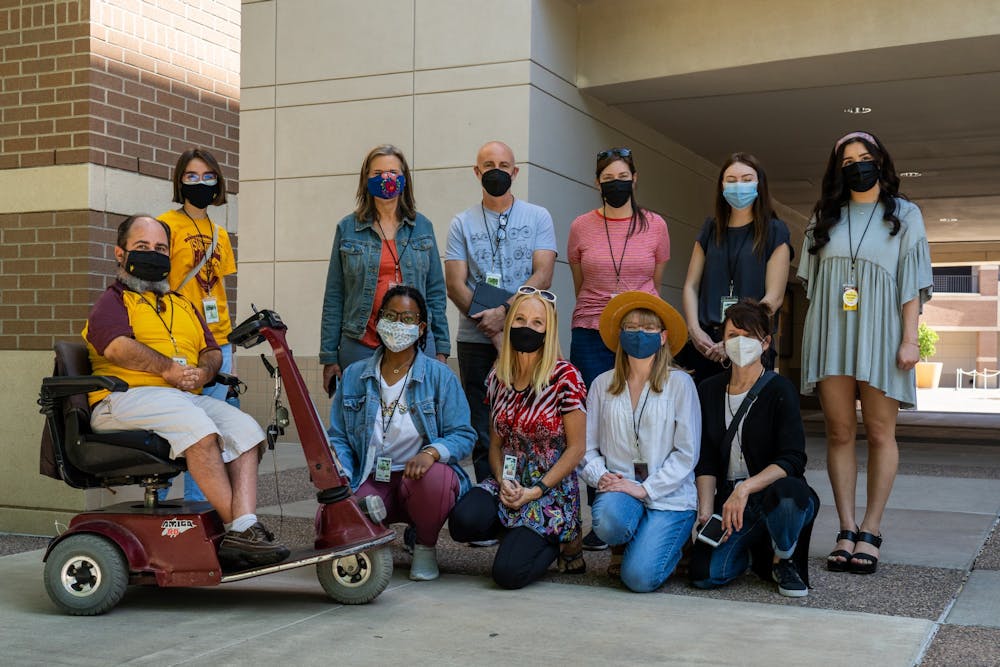

The event was organized by Mapping Access, a group of students aiming to create a readable campus map identifying accessible features for the ASU community. Together, they've spent the past two semesters collecting raw data.

"We really wanted to not only showcase that, yes, there is an issue with accessibility here at ASU and also disrupt it to do something very meaningful," said Christine Leavitt, a graduate student in women and gender studies.

At West, the team, along with volunteers, went out to collect building numbers, room numbers and accessibility details on two Google Forms. The data was used to create an accessibility layer on ASU maps, which viewers can use to find accessible routes on campus by clicking the layered icon on the left side of the website and checking the "accessibility" box.

Over the course of two hours, the volunteers had mapped the entirety of the campus — recording enough information to update the accessibility layer on the West campus map. The data was then ready for Karen Fisher, an ArcGIS developer at ASU, to put it on campus maps.

Already, the group has mapped the exterior entrances to buildings on all four campuses.

At the West campus, an unmarked water feature sits between Kiva and Sands buildings. The pool has no guardrails or warnings, so a wheelchair user, someone with limited vision or anyone who is distracted could easily fall in.

Unmarked hazards like the pool are not on the campus layer, but Mapping Access hopes to implement geofencing, a virtual geographic boundary system to audibly notify users of obstacles or features in their path.

"When a person who is blind is walking close to a building, you'd say, within 100 feet of the building, 'You're approaching the psychology building,'" Fisher said.

Fisher hopes to incorporate the geofencing feature into the accessibility map so users can navigate between the visual map and the audio wayfinding with the check of a box.

Currently, the accessibility layer with data on the exterior entrances is live and intended for use not only by members of the disability community but by anyone who wants to efficiently travel across campus.

"Everybody has access issues, and the access for some leads to better access for all," Leavitt said.

READ MORE: ASU students join together to create an Accessibility Coalition

Building the team

The Mapping Access team formed out of a Humanities Lab class, Disrupting Dis/Ability. The course ran in Fall 2020, allowing students to form groups to examine disability justice and explore projects of their own choosing, said RaNiyah Taylor, a junior studying political science and family and human development.

Taylor's group, which included Jaulus and Jordyn Stebbins, a junior studying health sciences, came up with the idea to make a more accessible campus map based on examples from other universities across the country.

The team started a Facebook campaign outlining why an accessible map at ASU was needed, and several simple demands to make it usable for all, Taylor said.

At the same time, another group of Leavitt, Samantha Gillette, a senior studying molecular biosciences and biotechnology and Melissa Richardson, a graduate student studying social and cultural pedagogy, made a video blog documenting accessibility challenges ASU students face on the Tempe campus.

When the first group initially mentioned its idea for making an accessible map on campus to the second group, Leavitt said it was "like a light bulb."

The two groups became one, and took to the Tempe campus, gathering data, marking accessible entrances and exits, and preparing the data to be placed in the map layer.

"As you look at all these other campus maps, even they have an accessibility layer, they have accessibility routes, they have accessibility wayfinding," Leavitt said. "ASU, the most innovative university, had none of this."

Although the Disrupting Dis/Ability lab is over, the core group of students has continued to work on the accessibility layer in Beyond the Lab, a program that extends a Humanities Lab project, allowing students to keep making a community impact.

READ MORE: 'Voices of ASU' zine chronicles students' stories of ASU Counseling Services

Accessibility at the University

Jaulus and Richardson, who both use wheelchairs, were on their way to the Polytechnic campus to accompany Peter Fischer, coordinator of accessibility and compliance and liaison to the Mapping Access group, on a compliance walkthrough for a building that will potentially be remodeled when "the seats on the (ASU shuttle) were not able to be moved to accommodate two wheelchairs," Jaulus said.

Richardson and Jaulus did not want to be separated, so they waited for a bus that could accommodate them both. The bus arrived, and when Richardson's wheelchair was loaded onto the hydraulic ramp, the ramp broke.

"One of the bus drivers, in a rather insensitive comment, said (Richardson's) chair was too heavy for the ramp, to which we said 'No, your ramp doesn't work,'" Jaulus said. A mechanic was called to fix the ramp.

On the ride back to Tempe, there was still no bus with adequate accommodations, so Jaulus had to transfer to a standard bus seat, his wheelchair next to him not tied down because the bus had only one set.

Although ASU accommodated Jaulus and Richardson when they traveled to the West campus for the March 19 event, Jaulus said the incident was a good example of "infrastructural failure at ASU."

Inaccessible features, some of what Mapping Access identified during the event, continue to riddle the four campuses. Too-small elevators, sinks placed too high, unmarked stairs and a lack of button-powered doors are all barriers to accessibility on campus, the students have found.

Fischer, who works on ensuring buildings and spaces at ASU adhere to accessibility compliance laws, said fixing inaccessible areas can be complex. When he checks for accessibility compliance, he must refer to multitudes of regulations and building codes.

"I'm looking for thousands of ideas and processes, but largely, I'm looking for not just physical disability access, but all disability access for use of a space," Fischer said.

The University follows the federal Americans with Disabilities Act, the International Building Code and the Arizona State University Project Guidelines, Fischer said.

In 2019 and 2020, ASU spent $1.4 and $1.7 million respectively in remediation of accessibility items, according to internal tracking of funds by Fischer.

He recognizes not every accessibility issue can be practically handled, since many buildings on campus were built before ADA and University standards were mandated.

For example, an inaccessible elevator may not be easily exchanged for a more accessible one without doing major building renovation.

However, Fischer is always asking what else can be done to aid in accessibility, much like the Mapping Access team.

"Every student, faculty and staff member at ASU should have equal access and inclusive way of using our facilities. That's how I work," Fischer said.

Creating an accessible campus map

Once Mapping Access settled on the goal of providing the ASU community information on accessible pathways, the team had to find out how to transfer raw data to a map.

The team thought it was going to need to learn how to program a map themselves, Leavitt said, but realized instead, it would need to find someone to help them.

"I remember ... really being nervous about that. Because we're asking someone to spend a lot of time doing something that's probably not even on their radar," Leavitt said.

The group got in contact with Fisher, who works on ASU's maps.

Fisher is able to input the data Mapping Access collects in the field and transform it into a clickable layer in just a few weeks by using ArcGIS.

GIS stands for geographic information system. The system can deal with "any type of data that has space and time tied to it, which is most anything that you can think of," she said.

ArcGIS mapping allows a user to see a feature or location in relation to other landmarks. ASU has been using ArcGIS for the past few years to be able to develop maps in-house, as opposed to using a third-party developer, she said.

ArcGIS layers maps on top of one other, allowing users to select which features they want to see.

Fisher is also working on rolling out a wayfinding feature, where the map routes the most accessible, quickest pathway from one accessible entrance to the next, depending on where the user is going.

"I'm (working on) the technology parts. I have to do all the back end, but getting that data, actually going out and finding where it's located, is a lot of manual labor," Fisher said.

But Mapping Access is more than willing to collect the data in the field, and the team is grateful for the support ASU staff has given them.

"They definitely deserve to be recognized for going above and beyond to make sure that this accessibility layer is added," Leavitt said.

Looking forward to a more accessible University

With each mapping event, Mapping Access gets closer to its goal of charting accessible features at ASU. The group hopes not only to raise awareness about the challenges that come with barriers but to help all students find a way to navigate ASU's campuses.

"We all experience accessibility different(ly) and so having lots of different bodies and different people there is very helpful for our project because there's a lot of additional potential markers we could be adding to this map that are very needed," Leavitt said.

Student input is crucial as barriers to accessibility are found everywhere, possibly within the accessibility layer itself. With all of the layers enabled, the icons on the map can be a little bit overwhelming for those with limited vision, Jaulus said.

To remedy the issue, Mapping Access is considering splitting the accessibility layer from the other campus map layers to avoid crowding.

But before the group makes any decisions on changing how the map is delivered, they aim to crowdsource as much as possible, Leavitt said, by asking actual users their opinions on the map's features.

"Because there's really no point in having this layer if it's not an accessible type feature that you can even access," Leavitt said.

As the team has learned, there is no single solution for creating an equitable campus, but Mapping Access will continue getting boots — and wheels — on the ground to help all students find their way safely and efficiently.

"We just want to open people's minds" to the existing barriers on campus, Richardson said. "ASU is a lot better than most campuses. We just wanted to build it and make it a little bit more fluid and better."

Reach the reporter at alcamp12@asu.edu and follow @Anna_Lee_Camp on Twitter.

Like The State Press on Facebook and follow @statepress on Twitter.

Continue supporting student journalism and donate to The State Press today.