Catherine O’Donnell and Mark Tebeau knew the world was approaching a major historical period as university closures became more extensive near the end of spring break.

As historians, they wanted to create an archive where people from across the world could document their experiences during the COVID-19 pandemic. In a matter of days, this idea became “A Journal of the Plague Year: An Archive of COVID-19.”

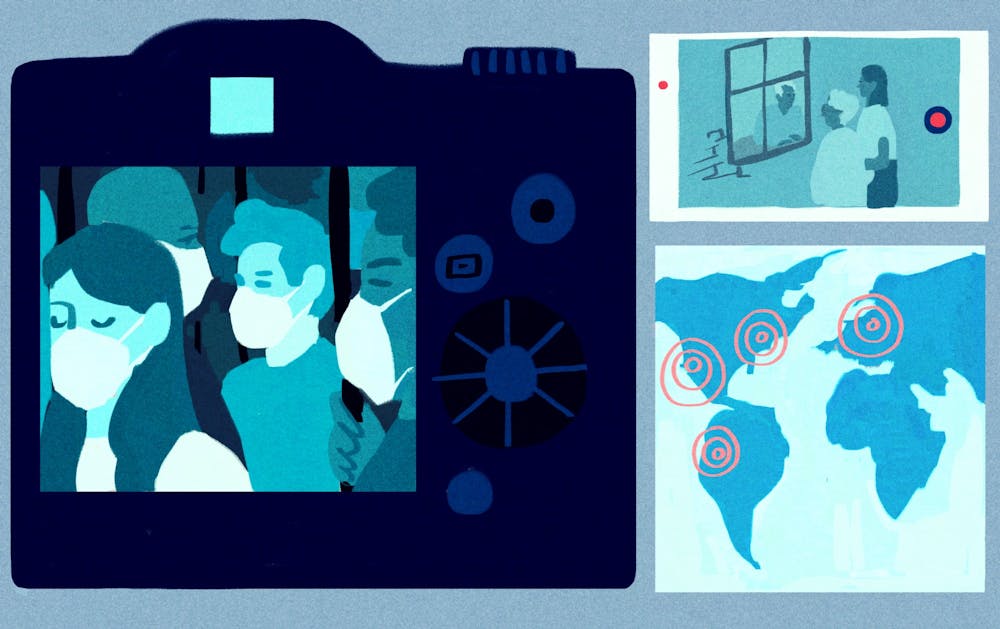

The archive is a website dedicated to collecting photos, videos, documents and other submissions in order to provide a comprehensive look at life during the COVID-19 pandemic.

The website's name was inspired by Daniel Defoe's 1722 novel, "A Journal of the Plague Year," which tells the story of a man during the bubonic plague in London.

In a little over three weeks, the archive has collected over 1,000 submissions from around 400 contributors. What started as a project in the ASU history department has since spread to schools and contributors worldwide, reaching places like Australia, Peru and China.

At first, the archive mostly consisted of what O’Donnell called “the plague of things not there.” People uploaded an abundance of photos of empty grocery store shelves and quiet streets.

Now, the archive is seeing a greater diversity of content from links to TikToks to videos of children talking through backyard fences to messages from indigenous leaders about how their communities are being impacted.

“It's kind of nice to have an excuse, just as a human being to tell another human being, what you're thinking matters, other people care about what you're thinking,” O’Donnell said. “So there's this kind of communal part of it that's somewhat separate from the scholarly part of it.”

A challenge in maintaining the site is convincing people their stories are important and interesting enough to contribute. Although uploading a document or photo to the site only takes a few minutes, Tebeau said people still hesitate to do so.

“The other thing that stops them is actually the thing that stops so many students from getting their homework in on time, which is this feeling that has to be perfect, and it doesn't,” Tebeau said. “It just has to be genuine.”

Before content goes live on the site, it is curated by a team of history students and professors from a number of universities to ensure it is formatted correctly. Outside of assigning subjects and tags to submissions to make them searchable, curators leave the majority of content unchanged.

“We're not spell checking, we're not content tracking, we're not saying this is a good contribution, this is a bad contribution, we're merely ingesting it and trying to give voice to it,” Tebeau said. “Archivists will tell us that no curation is ever perfect.”

The creators of the site strongly encourage contributors to make their submissions public but provide the option to keep content private once submitted. This content will only be accessible to future researchers. Out of over 1,000 submissions, only one has been modified by curators.

“You're not going to be able to understand this moment if you don't understand that people thought it wasn't real, if you don't understand that there were all these arguments, that it created ethnic prejudice, that people suffered in those ways also, so that stuff has to come in," O'Donnell said.

Clinton Roberts, a graduate student studying history, decided to post a photo to the site after hearing about it in a Facebook group. In the photo, his girlfriend is sewing masks for Roberts' cousin who had to work in an ER without a mask.

“I think in the long run, I'll be really happy to see that I took that step and preserved that,” Roberts said. “For my girlfriend too, I would really be appreciative of everything she's done up to this point anyway, but for her to sew something for my cousin, that's personal too, like that's really important to me.”

The archive not only gives people the chance to share their stories but also to see perspectives they wouldn't be exposed to otherwise.

Erin Craft is a graduate student studying history and works as a curator for the archive. A submission that was particularly impactful for her was an Instagram post from an LGBTQ support account about safe chest-binding methods during COVID-19.

“It never would have occurred to me that that would be something that could be an issue and something that people would need to know about,” Craft said. “That was kind of cool to see how different groups respond, and what they're thinking about, what they're worried about.”

Reach the reporter at gforslun@asu.edu and on Twitter @GretaForslund.

Like The State Press on Facebook and follow @statepress on Twitter.