Jewell Parker Rhodes still remembers the day she received a phone call from the school dean about her son's behavior.

He didn't assault anyone or even yell at anybody. He didn't have a weapon. Like most children, he was just upset at a situation at school. And yet, when she arrived at the school, she was told that next time, administrators would call the police.

She was shaken to her core. But the reality of how her biracial son was treated sparked an idea for a novel.

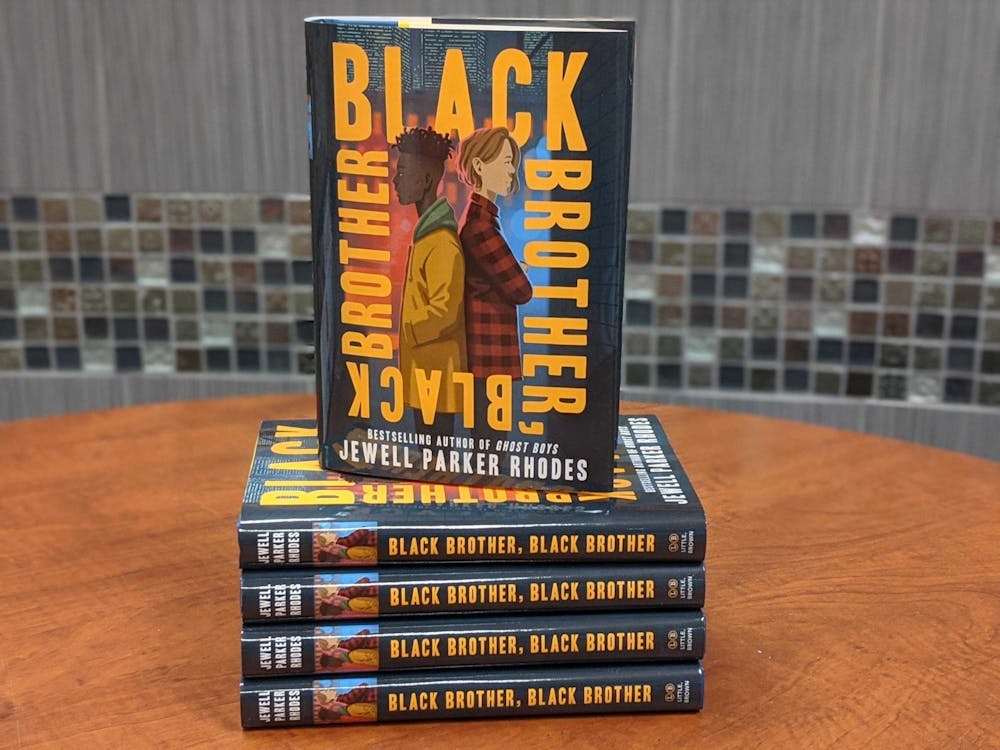

Rhodes currently serves as the Piper Endowed Chair and founding artistic director of the Virginia G. Piper Center for Creative Writing at ASU. She is also a best-selling author and released her new middle-grade novel “Black Brother, Black Brother," on March 3. It is a coming-of-age story about two brothers — one who presents as white, the other as Black — and the complex ways in which they are forced to navigate the world, all while training for a fencing competition.

Rhodes has a unique ability to create these captivating, quickly-paced novels about stories that are so relevant in today's society but rarely written about in the media. "Black Brother, Black Brother" is one of those — a powerful story about racism, privilege and overcoming adversity.

Rhodes said she tries to incorporate the African-American oral storytelling tradition that she grew up with while living with her grandmother in Pittsburgh into her writing style.

“I’m trying to make children talk stories the way my grandmother talked to me and imparted wisdom on to me,” Rhodes said.

Tough subjects are a recurring motif in Rhodes’ works. Her 2016 novel “Towers Falling” examines the effects that the 9/11 attacks have on children born after 2001. Her 2018 novel “Ghost Boys” follows the ghost of a 12-year-old boy named Jerome after he is shot by a police officer. He then meets Emmett Till and learns about the many wrongful deaths of young Black children.

Her latest work is about a child named Donte, who isn’t accepted by his peers at his prep school even though his lighter-skinned brother is one of the most popular kids. The plot is based on Rhodes' son's experience of going to a private school and facing prejudice because of his skin color.

Along with her son's experience, Rhodes was inspired to write the story after learning about the school-to-prison pipeline, which describes the disproportionate incarceration of students from marginalized backgrounds.

In her work, Rhodes tackles topics that she feels most children aren’t aware of until they become older.

“There’s a lot to think about, and I don’t want to patronize children,” Rhodes said. “I’m using oral storytelling traditions to make it accessible to speak about hard issues such as bias and discrimination.”

Rhodes is optimistic for the future, as she believes more middle-grade novels are allowing these conversations to happen between children and their parents or teachers.

In just a couple of years, these children will become full-fledged citizens: They will join the workforce, go to college and be able to vote. She feels that it is our duty as adults to prepare them by having them be aware of these issues that are in our society.

This is something I wish I had when I was younger.

“Black Brother, Black Brother” struck a personal chord with me. Even though I'm not Black, I saw myself in Donte as he was judged by his skin color and how the police treated him compared to his lighter-skinned peers.

I was 16 when I was escorted to my school dean’s office by a security guard. I thought I had gotten another behavior award or made the honor roll again, and they were just giving me my certificate.

However, when I walked into the office, I was surrounded by the dean and six police officers. A man who I had never seen before sat in the dean’s chair — we’ll call him the Detective.

“Please have a seat, Timothy," he said.

I obeyed, confused by the situation.

“I heard you got a new laptop recently," the Detective said.

This was true. I had bought a laptop off one of my classmates, John, a couple of months prior to this confrontation. The price was really cheap too, which I assumed was because John came from a rich family. He was the type to have the latest iPhone and latest pair of retro Jordan sneakers. Therefore, I figured he just didn't care much about the laptop he sold to me.

I didn’t say anything to the Detective but just nodded my head.

“Well, that laptop is stolen school property,” the Detective said. “It was stolen off the computer lab a couple months ago. We called you in because you were the latest IP address attached to the tracking device on the laptop.”

My heart sank because I knew this wasn’t going to end well.

“I bought it off someone, but at the time I didn’t know it was stolen,” I said.

“Where is the laptop now?” the Detective asked.

“It’s at my house. We can get it if you want,” I replied.

The Detective nodded his head and looked to one of the officers, who motioned for me to get up. I don’t remember the officer’s name, but he was kind. We talked about sports and school as he drove us to my house, and I grabbed the laptop.

When we got back to the dean’s office, the Detective asked if he could speak with me alone. Everybody complied and left the room. As I sat across from the Detective, I could feel him sizing me up.

“You can just tell me you stole it,” he said.

“I didn’t steal anything. The officer told me that John confessed.”

“He did say that he stole the laptop, but I think you also had something to do with it," he said. "Maybe John is scared to say something.”

“I’m sorry sir, but —”

“Don’t lie to me," he interjected. "This could've been much worse for you. I was planning on bringing the SWAT team to your house, putting a gun to your head as you woke up and probably taking your family in as well.”

I wanted to say something. I wanted to call for the dean and the other police officers to help me, but what would they have done? Would they believe me?

Ever since I got called out of class, I was treated differently. It didn’t matter that I was on the honor roll every year; it didn’t matter that I was on the academic decathlon team or that I volunteered as a tutor at the local elementary school. I was already guilty when they brought me in.

I was released by the police but received a suspension from school. But the worst part of that whole reaction wasn’t the suspension. My perception of the world had changed. I realized that not all police were there to protect and serve — at least, not if you had a certain skin tone.

Perhaps it wasn’t a racial issue, but all I know is that John was white, and I was not. I cooperated with the police, gave them their laptop back and apologized for the misunderstanding. John ended up having to go to trial and was required to do community service. Yet, the whole interaction made me feel like I was the one that should’ve been guilty.

I kept this to myself for years; not even my family or my closest friends knew.

However, as I read “Black Brother, Black Brother,” the memories came flooding back, and I felt compelled to tell Rhodes about my encounter because I wish I had these books when I was younger — books to tell me that the world sometimes isn’t all sunshine and rainbows, that there will be times where people will be out to get you. It is important because these stories aren’t meant to scare but to create awareness.

Besides writing children's books, Rhodes travels around speaking to schools and students. A powerful and passionate speaker, Rhodes captures the attention of audiences to spread her message.

Family and love are prominent themes in Rhodes’ work. In her new novel, we see the relationship between the two brothers, Donte and Trey, and their love and camaraderie.

“I love the relationship between them because they are brothers through thick and thin,” Rhodes said.

Rhodes hopes that her book will show readers the absurdity of judging someone based on their skin tone.

“Everybody deserves to be treated equally, and our children deserve safe spaces in order to grow,” she said.

At the end of our conversation, Rhodes recounts a story of when she was visiting St. Louis a few months after the death of Michael Brown. As she was walking, she saw a young man and asked how his day was going.

“Every day above ground is a good day,” the young man replied.

I’ve thought about this story often since I spoke to Rhodes. My mind shifts through the stories of young men whose lives have ended because of racism: Emmett Till, Michael Brown, Trayvon Martin.

I reflect on when I was the same age as they were when they died, and the realization of how short their lives were always blindsides me. I think about my first encounter with the police and how, with any wrong move, they probably would’ve taken me in. I thank Rhodes for writing these stories.

Every day above ground is a good day.

Reach the reporter at txayasom@asu.edu and follow @its_tim_x on Twitter.

Like The State Press on Facebook and follow @statepress on Twitter.