The threat of antibiotic-resistant bacteria is pushing researchers to study other viable options.

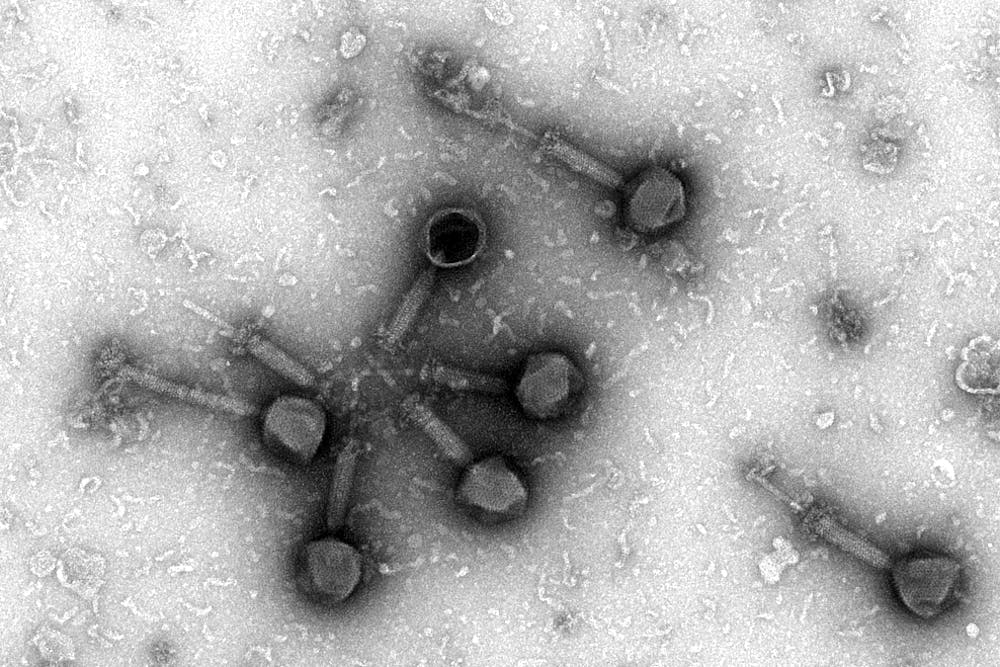

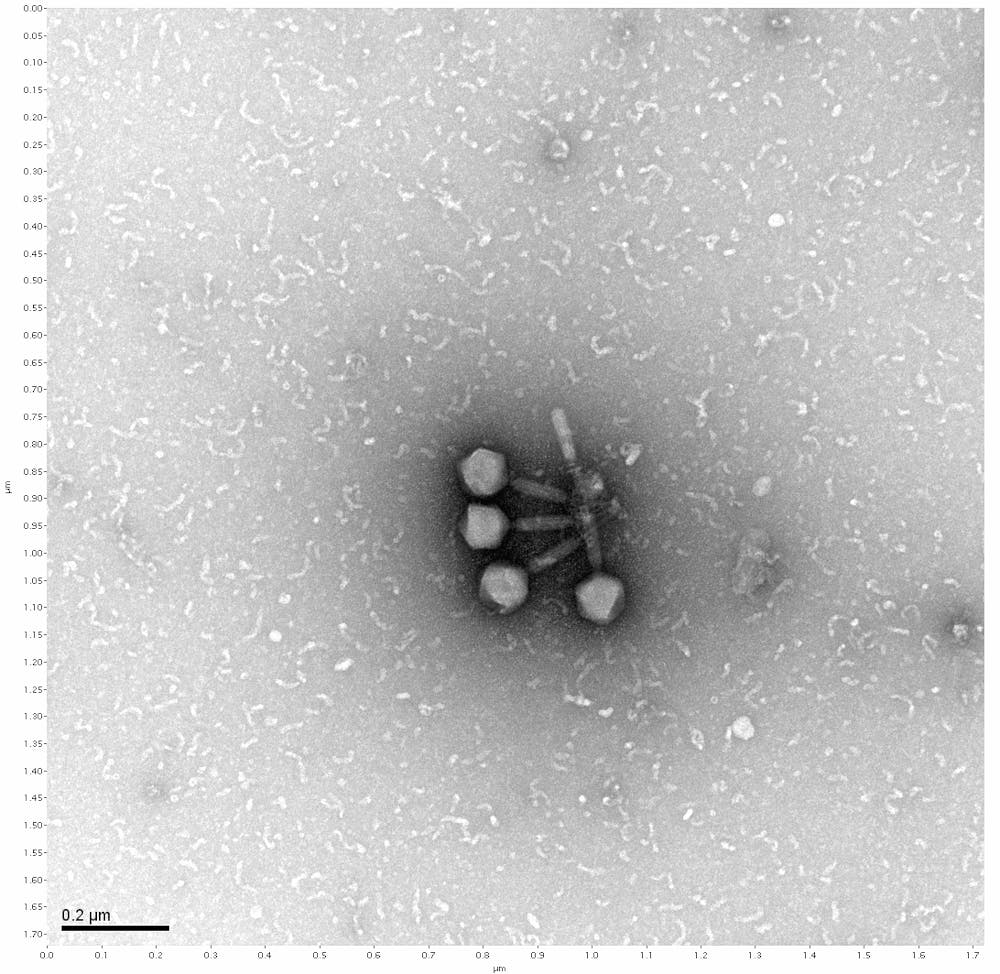

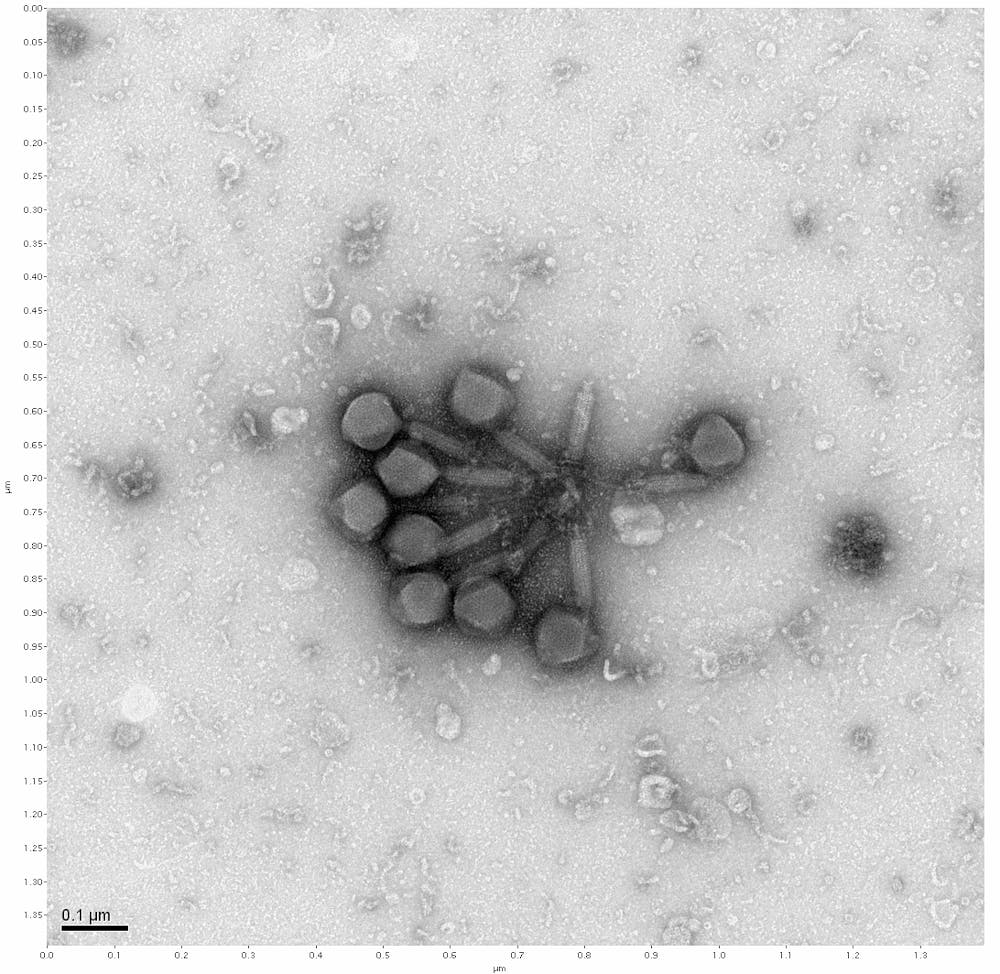

Bacteriophages, an old discovery widely disregarded after the discovery of antibiotics, is now being reevaluated by ASU researchers. A bacteriophage, which translates to "bacteria eater," is a virus that attacks bacteria.

Dr. Neema Mafi, an infectious disease doctor at HonorHealth, said phages are a virus and your body sees them as such. He said it's possible our bodies may start making antibodies against it.

Phage therapy is the therapeutic use of bacteriophages as a treatment for bacterial infections. Phage therapy is used to treat Pseudomonas aeruginosa, a pathogen known to cause severe infections, as shown in a 2019 study by BMC. Researchers found that Pseudomonas phage BrSP1, a phage that was separated from sewage, could be used in the treatment of veterinary infections.

Phage therapy was used in the former Soviet Union showing more improvement than antibiotics in cases of Furunculosis, Carbunculosis and Hydroadenitis. It was again used in the Winter War in the Soviet Union and Finland where the mortality rate due to gangrene, a condition caused by infection or lack of blood fIow that causes tissue to die, reduced to a third.

Bacteriophage was also standard treatment for dysentery for German and Japanese troops during World War II.

Although phage therapy has an overlooked history of being a safer alternative to combating bacterial infections, the growing threat of antibacterial resistance has intensified researchers’ desire to study phages.

Susanne Pfeifer, an assistant professor for the ASU School of Life Sciences, is leading a new year-long research class at the University for Barrett students called "Phage Hunters." The purpose of the class is to gather research on bacteriophages. This is part of a current effort to collect phage data, as there are different kinds of phages in the sea, desert and all other terrain. Phages are the most populous organism on Earth, Pfeifer said.

“They don’t do anything to you,” Pfeifer said. Bacteriophages only attack the bacteria, which, if true, means there would be few side effects for humans.

In fact, they are even easy to study, Pfeifer said. She said they are found in abundance and have tiny, little genomes, which is what the students were putting into databases in the Life Sciences Center in mid-January.

Each phage is different from the next. Researchers are currently trying to alter phages, and the next step would be to engineer phages. In order to fight bacteria, they must be engineered to fight different kinds of diseases for maximum effectiveness. At the moment, phage therapy is a mixture of different phages.

This research is coming just in time as antibiotic resistance is becoming a growing concern, Mafi said.

“We used to give antibiotics without thinking about the consequences,” he said.

One example of an antibiotic-resistant infection is the staph infection, also known as S. aureus. According to a study from The Journal of Clinical Investigation, "By the late 1960s, more than 80% of both community- and hospital-acquired staphylococcal isolates were resistant to penicillin." Soon after, this infection became resistant to methicillin, another type of antibiotic, Mafi said.

Some bacteria are inherently resistant to antibiotics while some develop resistance. If two strands of bacteria share DNA and one becomes resistant to antibiotics, the other may as well, furthering the problem of antibiotic resistance.

Typically, hospitals will keep track of resistant patterns, so every hospital has what is called “antibiogram,” Mafi said.

Students in ASU’s "Phage Hunters" class expressed a lot of enthusiasm and hope for the future of phages as a solution to antibiotic resistance. Bruno La Rosa, a sophomore majoring in molecular biosciences and biotechnology, explained how students collect their own phages from samples of dirt and then send them to the Howard Hughes Medical Institute at the University of Pittsburgh. He said the genomes are then returned in the form of a written code and the students analyze the quality of the genomes.

Avery Fry, a senior majoring in health sciences, talked about potentially moving some of the phages’ amino acids and nucleotides, essentially altering them so they can be paired to fight against a specific disease.

Treating bacterial infections with antibiotics may not work sometimes, but people could ideally have a phage engineered to infect that specific species of bacteria, Fry said.

La Rosa said bacteria and phages have been evolving next to each other since the beginning of their existence. In a way, they have been at war with each other, he said. But bacteria mutate so quickly that a cure might not work.

“Right now, we don’t really know a lot about phages,” Angelica Urquidez, a senior majoring in biological sciences, said.

She believes phages can be used as a treatment plan, but probably not a cure.

“It's a brilliant idea and at this point we are so desperate that we look for anything that works,” Mafi said.

He said that although we can make stronger antibiotics, the bacteria will continue to evolve to become more resistant to antibiotics.

Mafi is proceeding with cautious hope about bacteriophages, explaining that what happens in a lab might not happen clinically.

“In medicine, something makes perfect sense on paper, and then you bring it to clinical practice and all of a sudden you see all these unexpected results," Mafi said. "And it's just because the body reacts in different ways."

He said that even monoclonal antibodies are replacing chemotherapy as a cancer treatment. While monoclonal antibodies may still be an effective treatment for some cancer, Mafi said many patients can have adverse reactions. Some have even had their colons burst due to inflammation.

“Sometimes, you will be shocked that there's that much of difference between how antibiotics work inside the body versus how the antibiotics work outside the body,” Mafi said.

Variables such as pH and blood sugar levels are at play, whereas lab results are very pure, he said.

He encourages the idea of using antibiotics more sparingly — an idea he called “antibiotic stewardship.” Lots of things that are currently treated with antibiotics might not need antibiotics at all. If complete removal of antibiotics is not possible, he recommended using a narrower spectrum of antibiotics to limit the resistance.

Mafi compared phage therapy to the HIV virus. The HIV virus binds to a specific lymphocyte with specific receptors and then it couples its own receptor with a white blood cell. That white blood cell starts making the HIV virus and then it explodes. The difference is that in phage therapy, it's the phages bursting the bacteria.

Mafi said he worries about how often people can use phages, saying it is possible for it to be a one-shot occurrence.

“The same way that you have been exposed to bacterias in your life, you might have been exposed to phages too,” Mafi said, suggesting that our body is already familiar with phages. Our bodies' antibodies might fight that phage.

Mafi said, as an example, people might be able to use phage therapy to treat an E. coli infection once. But can people use phage therapy to treat an E. coli infection if someone gets the same infection again? It is not known if a person can become resistant to phages, but he said it should not be ruled out yet.

Mafi said if there is a resistance to phages, it would be nothing like antibiotic resistance.

Mafi also suggested that pharmaceutical companies might not want to invest in phages, as it could hurt them financially.

Another question Mafi posed about phages was whether or not they can make us sick. They are programmed specifically for the bacteria they are fighting, but the body is still going to react to them. Because phages are a virus, they could potentially cause a severe immune reaction and make someone sicker.

There are a lot of questions left to be answered about phages, but overall, students said it looks like use might come out of them.

Correction: A previous version of the story incorrectly stated the name of the antibiogram. The story has been updated to reflect this change.

Reach the reporter at edhortar@asu.edu or follow @ElsaHortareas on Twitter.

Like State Press Magazine on Facebook and follow @statepressmag on Twitter.