Editor’s note: This article contains offensive language.

Rashad Shabazz chose — no, he needed — to leave Chicago.

The month he left Chicago to go to college, someone was killed on the South Side.

The residents of a neighborhood had organized a block party. What was supposed to be a celebration in the neighborhood turned to mourning.

Attendees witnessed a 9-year-old boy shoot a 12-year-old girl in broad daylight.

“He did it right there, and everybody in the neighborhood saw him. Everybody in the neighborhood knew who he was,” Shabazz said.

The killer was never brought to justice. In fact, the same gang that ordered the boy to shoot an innocent girl killed him. Afterward, they dumped the boy’s body in an alleyway, Shabazz said.

“It was that kind of thing — especially young men who felt alienated, who felt powerless — having access to guns and dealing with conflict through force and violence, it just created a really toxic mix that continues to this day.”

Shabazz, now a professor of geography and black cultural studies at ASU’s School of Social Transformation and author of the 2015 book “Spatializing Blackness,” has spent a significant amount of his life trying to understand how the neighborhood he grew up in came to be, and how the 8 miles between northwest Chicago and the “black belt” on the South Side might as well have been two different worlds.

In a review of Shabazz’s book, David Ponton III said, “for Shabazz, ‘black masculinity’ becomes reconfigured as a consequence of these racialized prisons, producing cycles of gender performance among black men that devastate black communities in terms of violence, health and well-being, and economic stability.”

Nicole Mayberry, a doctorate student who Shabazz is an advisor for, said he approaches teaching from the perspective of equity.

“He’s a natural community builder and allows us to come together and work out ways we can situate our research,” she said.

In the spring of this year, he brought some of his graduate students to a national conference in Washington D.C. He introduced them there to geographers whose books the students read, said Brett Goldberg, a graduate student who went on the trip.

Shabazz studies under world-renowned civil rights leader Angela Davis and is currently working on a book to discover how the structure of Minnesota’s education system helped produce artists like Prince.

He educates the ASU community about critical race theory and the history of social injustice, knowledge that is key in today’s political and social discourse.

But all of his work follows a theme that traces back to his origins in the South Side of Chicago.

South Side living

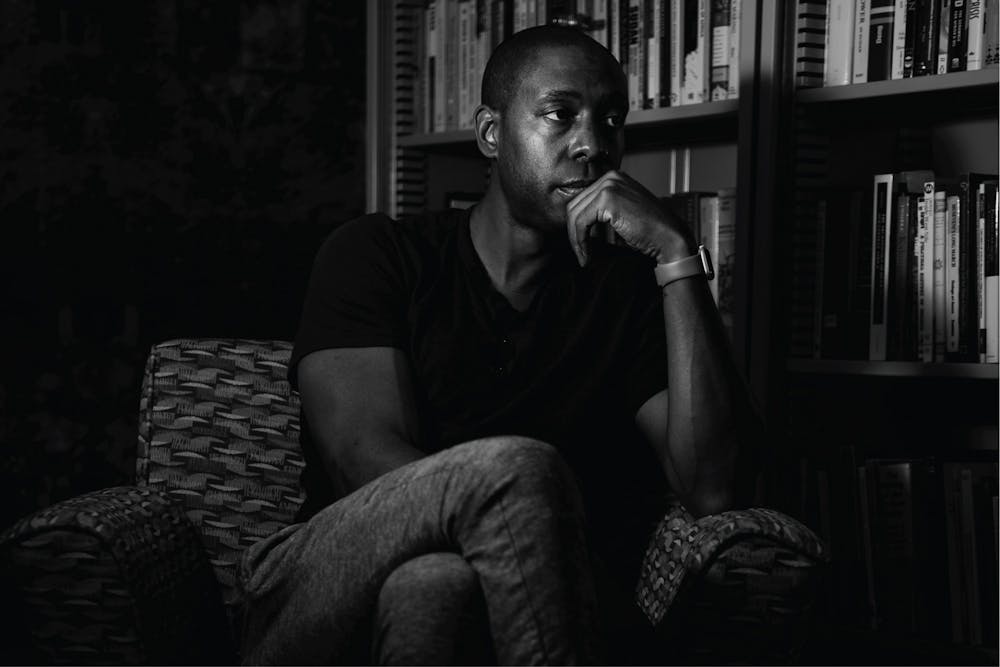

Inside Wilson Hall at ASU, Shabazz is sitting comfortably in a maroon plush chair surrounded by books encased behind glass, old maps of Africa and wallpaper of a cabin in the woods. Light from the window catches on his gold nose ring, and his deep-set eyes stare calmly into space.

Shabazz still carries the trauma of the South Side. He doesn’t sit with his back to the door, he said, out of an anxious habit to remain constantly alert of his immediate surroundings.

In the mid-80s and mid-90s, Chicago had between 664 and 943 homicides per year, according to the Chicago Police Department. Gangs carried out many of the murders, Shabazz said, but that was in part because people did not have faith in the police or the justice system.

Gangs sprang up to deliver “street justice,” but that only exacerbated the violence.

“Because we didn't count on the police, we didn't count on the justice system. The only thing that we knew would happen was that there would be some kind of street-level response,” Shabazz said. “We were really kind of caught between not having any faith in the justice system and also being fearful of the justice system.”

When rappers Ice Cube, Eazy-E, Dr. Dre and more formed N.W.A. in the late 80s and came out with their hit single “F--- tha Police,” Shabazz had a watershed moment.

“For many hip-hop heads and rap fans, and particularly for young black kids and kids who were under the thumb of the police, when ‘F--- tha Police’ came out, there was a song that said what we've been saying for years,” Shabazz said as he held up a middle finger.

Shabazz’s relationship with “F--- tha Police” is representative of one of his core findings in how law enforcement polices the black community.

Like many other children or teenagers, Shabazz and his friends hopped fences, ding-dong ditched houses and drank water from neighbors’ hoses, but that kind of mischief was “deeply criminalized,” Shabazz said.

The police followed black people — especially in white neighborhoods, accused them of wrongdoing and at times shot them, he said.

Because the police were hostile to young black men like Shabazz, he and his friends antagonized police. One of the ways they did this, Shabazz said, was by saying “F--- the police” while passing them, then running when the police tried to chase them.

“It was kind of a bit of a game until one time, we said it to them, and they pulled guns on us,” Shabazz said. “It was clear that it wasn't just an adversarial relationship. It was a relationship between whose life is valuable and whose life is not, and that they would be willing to draw their service weapons on little kids who just said ‘F--- you,’ and end our life.”

The origins of this interaction, Shabazz makes clear in his book, “Spatializing Blackness,” are not in the interest of law and order, but control and white supremacy.

“The Mike Browns of the world go back decades,” Shabazz said.

“Slumming it”

In early 20th century Chicago, Shabazz said, the perceived power of white people was being challenged in vice districts where drinking, gambling and prostitution were quietly accepted by the police. At the center of this racial struggle were popular destinations known as “Black and Tans,” named after the open interaction between blacks and whites.

But one captain on the Chicago police force, Max Nootbaar, viewed Black and Tans as a “crucifixion of whiteness” and a moral affront because of the interaction between races. There were two worries in the white community: Black and Tans spreading to white neighborhoods, and sexual proclivity.

“What the police were able to do, and what Nootbaar did was institutionalize a set of ideas about race into the politics of policing,” Shabazz said. “Literally, policing the color became part of their job. So … yes, they're all of these white supremacist and broadly racist and homophobic elements that are woven into the politics of policing.”

Many young white people frequented Black and Tans, but their parents weren’t happy with it so the term “slumming” evolved to describe young white people heading to black neighborhoods to go to these interracial clubs.

When Nootbaar became captain of the police force, he used his power to send police raids into Black and Tans in an effort to eliminate the association between white people and non-white people. This was illegal, and yet he only received punishment equivalent to a slap on the wrist, Shabazz said, and continued his crusade in black neighborhoods.

“He was in the best position to do this. He was a cop. He had the authority of the state right there at his hands,” Shabazz said.