According to the U.S. Census Bureau, I’m white.

White without the privilege, that is, because I'm not white.

Growing up, I was well aware that I wasn’t white — at least in terms of my skin color — but that was it. My thoughts were always: I’m Egyptian, and that’s that.

Gold-tinged skin that would get warmer each summer spent on the Mediterranean. Big, buoyant, black curls that graced the top of my head. My strong, defined side profile that I only saw in other Egyptians.

I grew up here in the East Valley, or more specifically, Chandler, Arizona. I attended a predominantly white elementary school where I looked nothing like my peers. It was something I always had to be reminded of.

Over time, what made me unique became my insecurities. I hated how I never fit into this Eurocentric ideal that was promoted everywhere I went. I just ... didn’t look white.

And now, with a hijab wrapped around my head, my identity is still very racialized. You’d think that people can tell the difference between faith and ethnicity.

However, when it comes to Muslims, it’s all one big misnomer. The lines between Islamophobia and racism are blurred.

Despite being a major religion of 1.8 billion people worldwide, we’re all lumped into this monolithic caricature of a brown immigrant.

So to others and myself, I should be considered a minority ... right? Not according to the census.

Census racial and ethnic categories are a confusing terrain to navigate. The census is not only exclusive of various identities, but in its nearly 230 years, the only consistency in the census has, in fact, been inconsistency.

There are many factors that determine why a certain racial or ethnic category makes it on the census, and that includes both in response to changing demographics in America but also as a result of what the majority is thinking.

For example, some East Asian identities had their own standalone ethnic categories when immigration from those countries increased. The category “Korean,” was an option from 1920 to 1940, vanished for a while, and returned again in 1970 when more Koreans immigrated to the U.S.

Other changes to the census were made due to inaccuracy.

From 1920 to 1940, the predecessor to the “Asian Indian” category was “Hindu.” This category had to be changed because it was mistakenly used to refer to an ethnic identity rather than a religious one.

After many mishaps with figuring out how to categorize race and ethnicity, in 2000, the census finalized its categories for race that we use today.

And now, with the 2020 census coming up, there is still no place for people from the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) region, despite the efforts made to include MENA as a category for race (including a proposal during the Obama administration).

It’s important to have this category in order to represent and understand more minority groups in this country. The region encompasses a total of around 22 countries and hosts a variety of different ethnic groups.

People who are from MENA are lumped into identifying as white, like 76.5% of the U.S. population, but they are still treated as minorities without official recognition of that status.

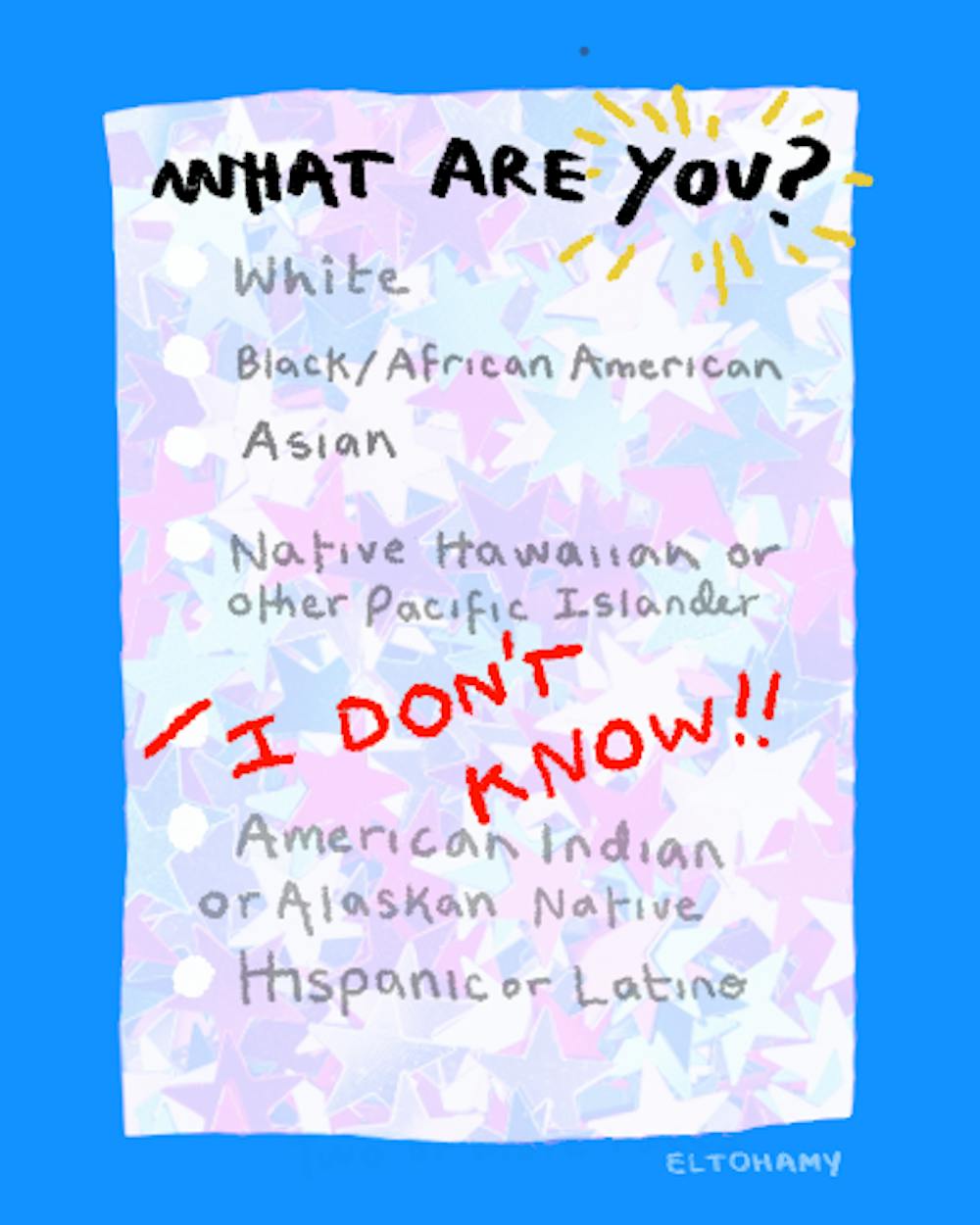

For someone like me, I never know which box to tick. I felt like this tiny checkbox, which in reality shouldn’t carry that much value in my life, was picking at me slowly. Taking the one thing I held onto the most: my identity.

Like many people from the MENA region, I don’t see myself as white. Neither does the world around me. I know my ethnicity, but the question of race has always been mind-boggling. I resort to choosing “Other,” and when referring to myself, I just call myself brown.

According to a 2016 report from The Atlantic, the “Other” category was the third most popular in the country. More and more Americans are choosing this category because they don’t feel represented by current government forms.

The problem with choosing “Other” is I personally feel like it is a cop-out. The category is vague and veiled in uncertainty. After all, what really constitutes as "Other?"

Especially for Egyptians, our race is something that is often debated. For me, there is no black or white, just the ambiguity of being brown.

I don’t know how I’ll identify myself on this next census. As disheartening as it is, I’ll most likely check myself as “Other” like I always do.

But it’s important to be represented. It’s important to feel like your identity is valid. And the end of the day, I know who I am, even if a government form doesn’t.

My identity is a hearty bowl of koshary after a gloomy day. It’s the countless Ahmed Helmy movies I grew up with. It’s the lightheartedness of the Egyptian dialect, colloquialisms that stray from the typical rigidity of the Arabic language. It’s the sound of the tabla in every, and I mean every, Egyptian song.

It’s being showered by endless warmth and hospitality from both family and friends.

Or how much of an abomination I think Trader Joe’s chocolate hummus is.

Editor's note: Farah Eltohamy is the editor of The State Press' podcast desk.

Reach the reporter at feltoham@asu.edu and on Twitter @farahelto.

Like State Press on Facebook and follow @statepress on Twitter.