In the fall of 2018, the political pulse of ASU’s Tempe campus was about to rise. A few protests peppered the start of the semester but would pale in comparison to the impending fallout.

In the early 2000s, the University received the longstanding moniker of “Apathetic State University,” from media outlets like the Phoenix New Times.

But political expression on campus was reawakened when local and national media outlets reported on the racist, sexist chat logs of College Republicans United, a fringe conservative club. Students then protested the presence of U.S. Customs and Border Protection recruitment on campus, ASU’s lack of responsiveness to marginalized communities and hateful posters plastered on multiple campuses.

The revitalized student body invites a reflection on some of the largest political moments at ASU. These memories, ranging from FBI surveillance to mandatory ROTC training, give current students a greater understanding of the University’s political climate over the years.

Ending the Mandatory ROTC Program

In 1968, the number of U.S. troops in Vietnam approached its peak of over 500,000, and young men from ROTC programs were largely called upon to fight the communist North Vietnamese Army.

“The Vietnam War is very much unlike the war in Afghanistan and the wars in Iraq because there was a draft,” said Margaret Tinsley, an ASU student at the time. “Boys in college whose grades slipped were at risk of being drafted and sent off to war.”

The Arizona Board of Regents made the Reserve Officer Training Corps (ROTC) compulsory for all male students in Arizona in 1948. The mandatory ROTC program required freshmen and sophomores to complete one hour of classroom study and one hour of drills per week.

Like the rest of the country, ASU students chose sides.

George W. Chambers, the president of the University Board of Regents at the time, oversaw the three state universities in Arizona. He told the Phoenix Gazette in 1967, “At one time, only the type of people who love to carry picket signs objected to a mandatory ROTC. But today, there are serious-minded, patriotic students questioning its value.”

In the fall of 1968, the Arizona Board of Regents voted to replace mandatory ROTC training at these universities with a voluntary program. This proposal was first rejected in April, but was reintroduced in October and adopted in November due to pressure from students.

A handful of students remained unsatisfied with the action of the administration.

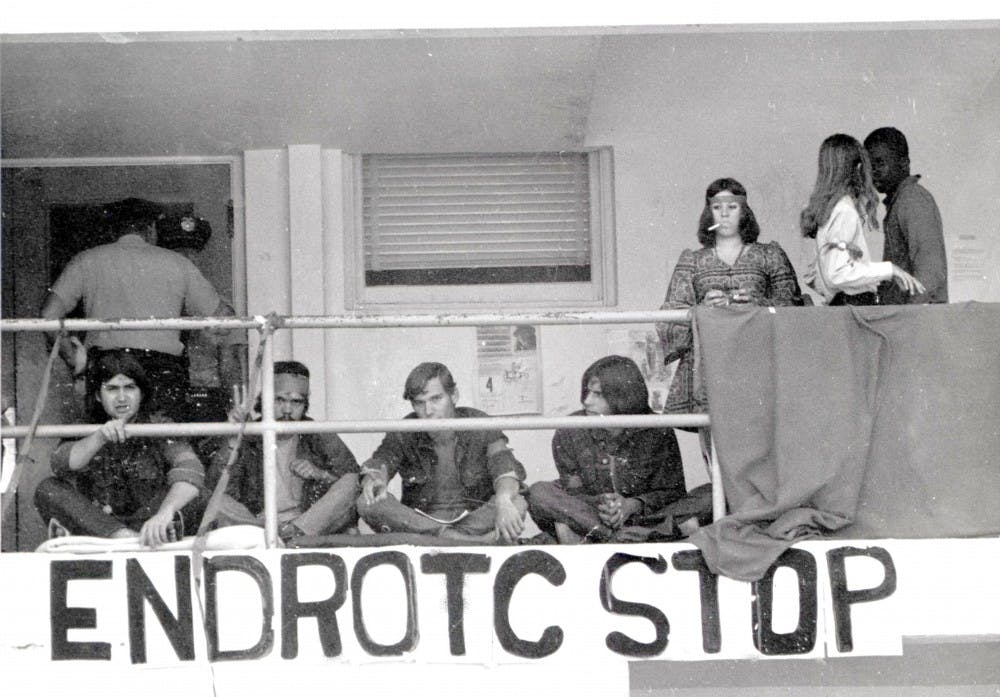

According to an ASU Libraries document, in the spring of 1969, 22 students began what would turn into a three day hunger strike, protesting for the removal of all ROTC training on ASU campuses. They occupied the ROTC building — now the University Club. A crowd of observers and students threw eggs at the demonstrators on the first night, and demonstrators shielded themselves with bed slats.

According to the document, rumors arose the second night that students opposed to the protestors would be backed up “by large groups of fraternity men, ROTC members, veterans, athletes or motorcycle gang members” to intimidate the protestors into relinquishing their occupation. More eggs were thrown at the protesting students that night.

The demonstrators frequently communicated with the campus security chief and other administrators to ensure that their presence was lawful.

On the third day, the campus security chief told the demonstrators they had two options: to leave voluntarily or be forcibly removed and arrested. Twelve students left and the remaining ten were arrested for “rout,” gathering with the threat of a riot, and “sedition,” rebelling against authority.

University administrators claimed that these students were arrested for safety reasons. Those arrested received the nickname “The Tempe Ten,” according to ASU archivist Rob Spindler.

In the fall 1969 semester, the voluntary ROTC program began. Only a few months later, the first nationwide draft lottery of young men for the Vietnam War took place.

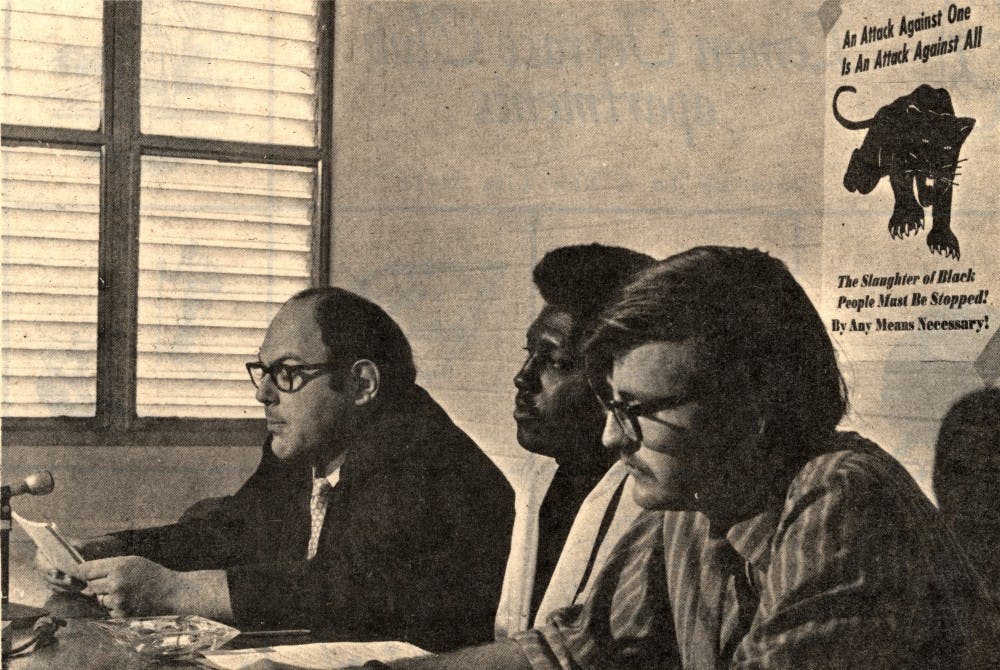

The Fall of Morris Starsky

Morris Starsky, an ASU philosophy professor in the 1960s, was described by Spindler as an “angry socialist.” Tinsley, a student of Starsky, described him as “out of step with the powers that be,” but “in the classroom, he was perfect.”

To the FBI, Starsky, a longtime activist and a leader in a Socialist Workers Party in Arizona, was considered a political threat.

During the 50s and 60s, the hysteria of the McCarthy-era Red Scare persisted. Many socialists and communists were perceived by the FBI as disloyal and dangerous to America.

Founder and head of the FBI J. Edgar Hoover created COINTELPRO, the program used to surveil Starsky in 1956, according to the Encyclopedia Britannica. The program ordered wiretaps and disinformation campaigns against people who were perceived as radical enemies of the American government.

The FBI began its surveillance of Starsky in the early 60s.

A 1963 letter from the Special Agent in Charge to J. Edgar Hoover said, “Morris J. Starsky, by his actions, has continued to spotlight himself as a target for counterintelligence action.”

In 1964, Starsky began his career at ASU, where he taught and continued to work with anti-war protesters.

Starsky’s son, Ben Starsky, learned more about his father’s life through letters and information he received from his father’s FBI file.

“There's also a very clear letter from the Special Agent in Charge of the Phoenix Bureau who identifies my father as one of the — or the primary — targets for disruption in the Phoenix area,” Ben Starsky said.

COINTELPRO turned its attention to institutions of higher education in 1965. According to FBI documents publicly released in 1976, falsified letters were sent to administrators and lawmakers to dismantle the efforts of left-wing activists.

A letter targeting Starsky in 1968, according to COINTELPRO documents, said he was “maliciously disturbing the peace” and “applying violent, abusive or obscene epithets” to the assistant director of the Gammage Auditorium outside the auditorium box office.

Starsky was fined $220 for the incident, the Phoenix Gazette reported, which is valued at over $1,500 in 2019 according to an inflation calculator. State representatives cited his alleged conduct in the manufactured letter from the FBI as reason for the fine.

Despite this, Starsky continued to attend protests and speak to crowds, and in the spring semester of 1970, Starsky’s life in academia began to crumble.

On Jan. 14, 1970, Starsky canceled a class to speak at an anti-racism rally at the University of Arizona. He was accused of improper use of his position and a formal hearing was announced to explore all related charges.

A faculty meeting passed a resolution on Feb. 2, 1970, not to fire Starsky. On Feb. 24, 1970, the Arizona State Board of Regents took over the case and ordered a formal hearing of charges against Starsky.

The Regents’ report said Starsky occasionally violated rules, had acted unethically citing the standards of the American Association of University Professors and “displayed exceedingly poor judgment in his relations with his colleagues,” the Arizona Republic reported.

“I was appalled that they would (fire Starsky). That just seemed ridiculous to me,” Tinsley said. “I’m sure that if you were more of a conservative person than I, you’d say, ‘Well he’s a communist, we should fire him.’”

Ultimately, Starsky was fired and blacklisted from other universities.

Starsky went on to work in a steel mill to provide for his family before his declining health forced him to retire in 1978 and live off of disability checks. Starsky died from a heart condition at 55 years old in 1989, according to ASU Archives.

A Race Riot and an FBI Investigation

Around 1 a.m. on April 15, 1989, four black students left a party at the Sigma Alpha Epsilon fraternity house, and a case of mistaken identity spiraled into a racial riot.

Upon leaving, hundreds of people surrounded the students outside the SAE house, which predominantly consisted of white students, and began to shout racial slurs at, spit on and harass the black students, according to the police report of the incident.

Officer James Klosterman said in his report, “I continued to encourage the black males to leave since more and more people (white) were beginning to gather. I could hear others yelling (racial slurs), but was unable to identify who they were. They were within the immediate area. The crowd now was beginning to surround us (four blacks and myself) ..."

The rowdy crowd began to break off into fist fights and University police officers on the scene called for backup. When deputies and patrolmen arrived, they began to mace the crowd.

Police took two of the four black students, who were members of the track team, into protective custody. With mace in their eyes, they were handcuffed to furniture when they arrived at the police station, even after they stated that the handcuffs were “too tight,” the Phoenix New Times reported.

Nobody involved in the altercation was charged with any crimes, and an ASU PD spokesperson said the students were handcuffed to follow policy.

The altercation was in direct response to an event from earlier in the evening when a different group of men — one of whom was white — assaulted SAE fraternity member Sean Hedgecock and others on the SAE front lawn, according to witnesses who spoke to the Phoenix New Times.

But the black students leaving the SAE house in the early morning of April 15 were not part of the group of men who allegedly committed the assault.

Coverage by The State Press over the following week dove into the racial implications of the incident. This spawned an FBI investigation into the conduct of ASU Police that night.

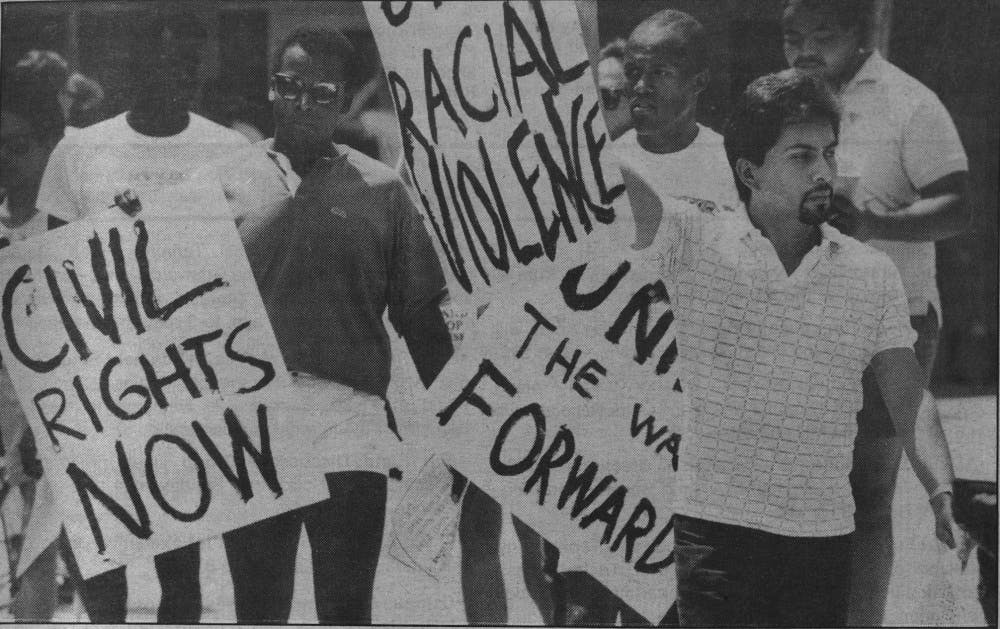

An eight-and-a-half hour sit-in and march was held in protest, where over 600 ASU students and faculty members participated, becoming the largest civil rights protest in the University’s history, according to The New York Times.

Amid student demonstrations, the Department of Justice and the FBI launched a collaborative investigation into the actions of police to determine whether they violated students’ rights.

ASU President J. Russell Nelson launched a 13-point plan to combat racism in the wake of the controversy, according to The State Press. The plan included an investigation into the police’s actions that night and recommended students take an ethnicity course, The New York Times reported.

The FBI did not find wrongdoing by the police. Mike Burgess, a reporter for The State Press, interviewed the two black students, Robert Rucker and James Liddell, who were arrested on April 15. He asked them about the investigative process.

“I’d call it a weak investigation,” Rucker said to Burgess. “How can you conduct an investigation without talking to the victims?”

Through the lens of today

“It was a horrible time. 1968 was a horrible year,” Tinsley said. “But it’s worse now.”

Current generations facing controversial federal government entities mirror the spirit of defiance present on campus in the 1960s.

In April 2019, ASU students protested the presence of U.S. Customs and Border Protection recruiting students for various jobs on the Tempe campus, according to The State Press.

The FBI surveilled Morris Starsky for years because of his political ideologies. Similarly, Turning Point USA, an organization that aims to teach conservative ideology to college students, maintains a Professor Watchlist. The database aims to “expose and document college professors who discriminate against conservative students and advance leftist propaganda in the classroom,” according to its website.

Professors across the United States and teachers who have appeared on the list have received death threats for their perceived liberal bias.

And on March 26, 2019 when Kevin Decuyper apologized for the racist and sexist language used by members of his club — language he then used in his apology — the same racial slurs shouted on April 15, 1989, echoed through the courtyard of Old Main once again.

Reach the reporters at cbudnies@asu.edu and follow @Chase_HunterB on Twitter.

Like The State Press on Facebook and follow @statepress on Twitter.