A young pregnant woman paces cautiously around a massive lake in Southern California, eyeing the dead tilapia lined up on the beach and "hoping that whatever has destroyed the water does not destroy her baby."

This scene, which highlights the effects of human-related damage to the Salton Sea in California, is from the story “Orphan Bird" by Leah Newsom, a creative writing graduate student at ASU.

The story was one of several featured in the second volume of ASU's "Everything Change: An Anthology of Climate Fiction," a collection of stories aimed at portraying the "grief at the damage climate change is doing to some particular place and culture," science fiction writer Kim Stanley Robinson wrote in the book's foreword.

Robinson, a Hugo-award winning author and lead judge for submissions to the anthology, highlighted both the power and short-comings of science in tackling environmental problems.

“Science can figure out how the physical world works and how to manipulate that physical world,” he said. “But when it comes to what we should do as a civilization, the sciences look to the humanities and people’s values. The scientific community is like Frankenstein waiting for the brain to tell it what to do.”

The anthology, a product of a partnership between the Center for Science and the Imagination and the Virginia G. Piper Center for Creative Writing, is available to download free online.

Newsom said this is a project that could have only happened at ASU.

“For two centers to come together and create something as unique as this anthology, bringing together writers from all over the world, I think it's an incredible thing and something that would only really happen here," she said.

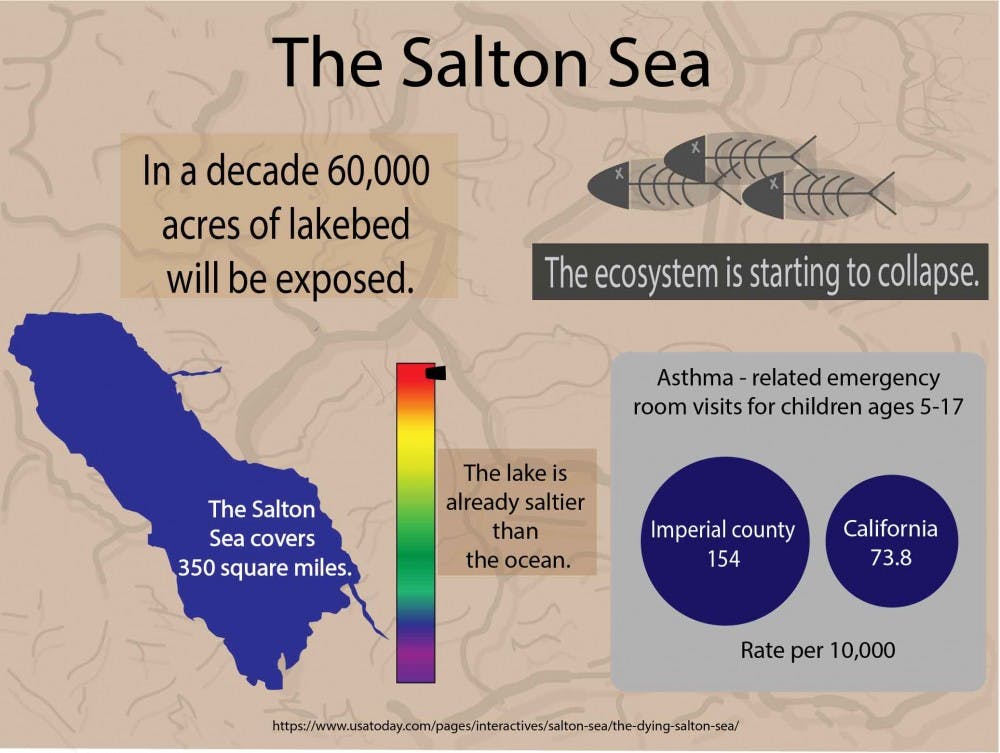

The Salton Sea, which Newsom described as “a mass grave," is shrinking rapidly due to water transfer deals directing more water towards cities, resulting in a slew of environmental problems, according to an article in USA Today.

Joey Eschrich, a program manager and editor for the Center for Science and the Imagination and co-editor of the anthology, said the themes in Newsom’s story were also reflected in other submissions.

“There were a lot of stories about fertility and childbirth and the human body being a precarious site in the face of destabilizing climate change and environmental collapse,” Eschrich said.

Angie Dell, the associate director of the Piper Center and the other co-editor of the anthology, said “Orphan Bird” was unique because it addressed climate change less through hard science and more through human connection.

“Her story was so much about love and human relationships,” Dell said. “That desire to have a family and see a future through family was so moving to me.”

Newsom said “Orphan Bird” is her first foray into climate fiction. While not her usual genre, she said she thinks climate fiction is important for making scientific knowledge accessible and digestible.

“(Climate change) is so complex that it can be easier for someone to say ‘I don’t understand it, I’m just going to pretend it’s not a problem,'” Newsom said. “Environmental fiction has a way of bringing people's thoughts into this larger world of understanding that they otherwise might not have access to or be so overwhelmed that they don't move into it.”

Eschrich shared Newsom’s view on accessibility, adding that fiction and the humanities generate much-needed empathy for others affected by climate change.

“Fiction, art and storytelling are a way to enhance empathy for other people and put people in others’ shoes, which is really important in regards to climate change,” Eschrich said. “Climate change is one big monolithic force, but it also looks different in each place that it happens.”

For Dell, emotional connection to the issues is integral to the environmental movement.

“If we can't feel that emotional draw into these important scientific problems and to these potential futures," Dell said," then I don't think that people will be able to stay engaged and care about things that aren't directly impacting them."

Reach the reporter at wpmcclel@asu.edu and follow @wpmcclelland on Twitter.

Like The State Press on Facebook and follow @statepress on Twitter.