A City at a Crossroads

In a cramped room at the Tempe Transit Center, just across the street from City Hall, officials presented the new Urban Master Overlay Plan to a full room of city residents. The purpose of the event, held on Sept. 20 and one of three that week, was to receive input from locals on the city’s long-term plans for what they define as Tempe’s urban core. Periodically, the light rail tram pulled into the station just outside the room’s far window. Each time, the presenter paused as the squealing brakes disrupted his train of thought.

The ambiance was apropos. Much of the meeting focused on patterns of development, which are intertwined with projects such as the light rail, Tempe Town Lake and those spearheaded by ASU.

Although the city has had some degree of success with these projects, the other focus of the event, albeit a subsidiary part of it, was affordable housing policy, underscoring the tension at the heart of development efforts. Residents also voiced displeasure over issues such as building heights and traffic, both of which are inextricably tied to patterns of development in Tempe and its urban geography.

The tenor of the event indicates the newfound sensitivity of the City Council to concerns over gentrification and costs of development. Tempe, one time an agricultural settlement, one time a post-agricultural suburb, is now urbanizing, and confronting the accompanying social challenges along the way.

Tempe is, in terms of development and the future of its urban core, at a crossroads. This leads to the pressing questions: What is the history of development and gentrification in Tempe? What were the historical forces driving the city’s evolution? What roles has Tempe played in the past in the Western states and the U.S. at large?

And, importantly, how has the city’s unique economic, political and social history shaped the urban form we see today?

Tempe’s Roots

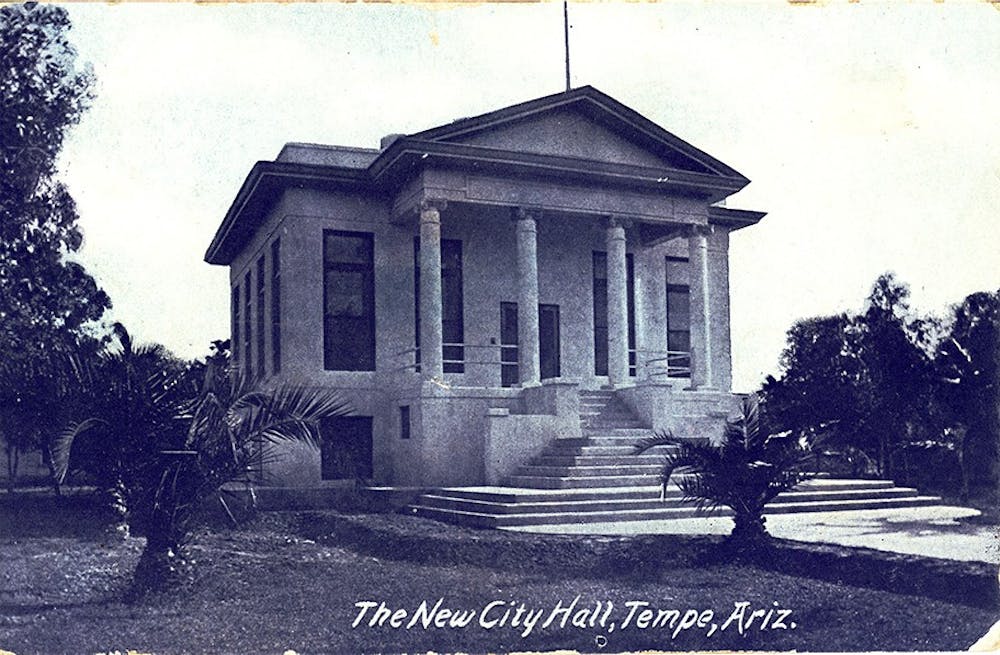

Tempe was incorporated in 1892 but first began as a collection of farms relying on irrigated water from the Rio Salado. During this period, it was settled primarily by white and Mexican-American farmers and ranchers, built on Akimel O’odham and Piipaash land. The form and function of this early agricultural settlement continues to have an impact on the evolution of the city.

The first Hayden Flour Mill (there would be three, the last being the one now standing) opened in 1874, east of Hayden Butte. Charles Hayden owned the mill, ferry and general store constituting the core of the town, which is now the Mill Avenue bar district. San Pablo, a largely Mexican-American community south of Hayden Butte, housed many of the workers that made Hayden’s business, and consequently Tempe, possible.

An event that would play a crucial role in the future development of the city was the 1885 founding of Arizona State University, then called the Territorial Normal School, with the purpose of training teachers for Arizona students.

Railroads and the waves of settlement they facilitated further changed the morphology of Tempe. The city was first connected to the rest of the United States by railroad in 1887. Shortly thereafter investors constructed new shops and housing, concentrated on Mill, Maple and Ash Avenues.

As Tempe grew in population, the boundaries of the residential neighborhoods continually pushed southward from what is now University Drive (a push that would only be thwarted in 1971 by the annexation of the hitherto unincorporated land south of Warner Road by the City of Chandler).

For most of its early history, the city was agricultural. The industry that was present mostly served the needs of agriculture and husbandry: both the Hayden Flour MIll and the Borden Milk Company Creamery. It was the Mill Avenue area that first became a center of business activity, sporting a bank and a variety of shops.

Construction of several dams upstream of the Salt River, beginning in 1902 with the Roosevelt Dam, allowed for further expansion of commerce and agriculture by providing a regular source of water and power to the Phoenix Metro Area. However, this would have consequences for the river and the habitat it supported as the sources that fed its watershed vanished.

Tempe on Wheels

Like all American cities, Tempe’s geography was altered by the rise of automobiles and the policies that encouraged their use. From the 1910s to the 1940s, several state and federal infrastructure programs made the city a hub for traffic moving along highway routes that spread out and knotted through the Western U.S. countryside; the US 60, a corridor once carrying motorists from Virginia to California, then passed through Mesa, Tempe and Phoenix.

Throughout this time period, Tempe also reflected the racial politics of the nation.

Mexican-American people had resided in Tempe since its inception and throughout the early 20th century. Amidst growing nationwide hostility to racial minorities, Mexican-Americans were subjected to discrimination and social marginalization in the city they helped build. For instance, the city forced Mexican-American children to attend separate schools than white children, which led to one of the earliest desegregation cases in American history in 1925. The case involved a scheme by which Hispanic children were to be taught by untrained teachers from the Territorial Normal School of Tempe. When a public swimming pool was opened in 1923, Mexican-Americans were barred until 1946. Even then, they were only admitted under special rules. Additionally, black people were barred from living in the city around this time.

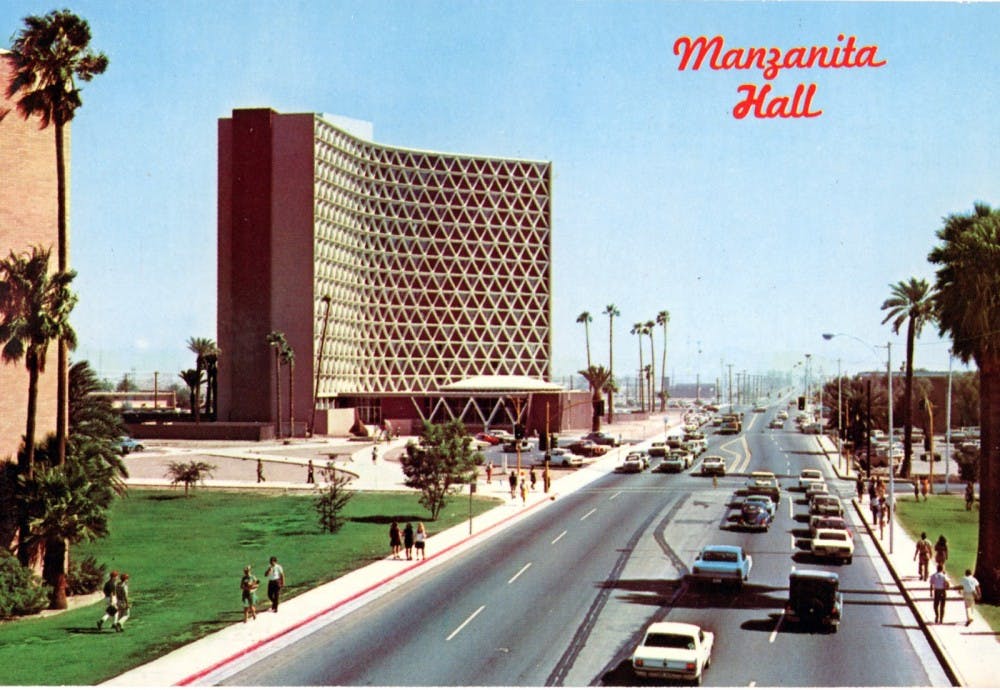

The onset of the Great Depression in the early 1930s and World War II in the 1940s dampened the growth of ASU. However, the future University bloomed in the fertile soil created for America’s higher education system by the GI Bill and the subsequent waves of student enrollment that resulted.

Expanding enrollment and programs fed the growth of the University into its immediate surroundings. For instance, in the mid 1950s, the City of Tempe and the University used eminent domain to wipe out the San Pablo Barrio, located at the base of Hayden Butte. This was done in order to provide ASU with land for student housing and Sun Devil Stadium.

According to “A People’s Guide to Maricopa County,” a collaborative project undertaken by ASU students in 2013, “The residents were forced to move, and many ended up in what is now the area of Escalante/La Victoria. Others displaced by the expansion relocated to other barrios along the Salt River, or moved to other parts of Phoenix.”

The 1950s brought many changes to the character of Tempe. Over this decade, the city became characteristically and functionally suburban, as the US 60, then routed through Mill Avenue and Apache Boulevard, as well as the curved stretch around Gammage that connects the two, provided the backbone for Tempe’s redevelopment by way of car and subdivision. Between 1950 and 1960, Tempe’s population tripled, the influx buoyed by the University and the proliferation of high-tech industry.

Increasingly automobile-centric development in the city would alter the economy of Tempe, as well as the businesses that it supported. Capital left the central business district, clustered around Mill Avenue, to flow into the suburbs. New classes of businesses and industry, dependent on the automobile, replaced the former, small industry-agriculture complex. Car repair shops, motels, car washes and mobile-home parks went up.

Mill Avenue struggled to adapt to patterns of development that affirmed the centrality of the car that the densely packed district was not built to accommodate. Suburban shopping centers with ample parking were more suited to the car-dominated suburban lifestyle. In the late 1950s and 1960s, Mill Avenue experienced a period of decay and disinvestment as it lost its centrality to city life and became less attractive to shoppers within walking distance.

Just north, the often dry riverbed of the Salt River, a host to a variety of unsavory forms of entertainment, was considered an eyesore by many residents — an “an ugly scar in Tempe” according to the City. Also unwelcome by locals was the influx of hippie college students to Mill in the late 1960s, frequenting new businesses created by ASU alumni in the wake of Mill Avenue’s slump, something of a revitalization for the district.

Decreasing water usage, owing to the paving over of thirsty farmland in favor of residential housing, also made way for the restoration of the Salt Riverbed. Floods in the winter of 1965-1966 were a rude reminder to Tempe residents of what the Salt River was when the city first began.

Major Changes

In 1967, the City of Tempe published its first plan, the purpose of which was to inform future development. According to a 2014 Masters Thesis authored by Alyssa Gerszewski and published by ASU, the plan “provided a new framework for future land use, economic and cultural development, public-private partnerships, downtown redevelopment, and the accomplishment of other community projects and goals.”

Another plan in 1973 outlined the City’s approach to re-develop Mill Avenue. It involved a “mixture of new construction and preservation to maintain an ‘old town’ feel, and would recreate downtown into the commercial, residential, recreational, cultural and entertainment hub of Tempe.”

The late 1960s foreshadowed changes on Mill Avenue, and the plan for the Salt River would prove to be the historical precedents for the rapid changes Tempe is experiencing now.

On the one hand, it is important to not overstate the scale or completeness of the changes that occurred in the urban core. For example, Hayden Flour Mill did not cease operations until 1998, and many businesses from the counterculture era still exist on Mill to this day.

However, many others have closed or moved, such as the Gentle Strength Cooperative and Changing Hands Bookstore. A planned development, The Local, which is set to host a Whole Foods, has fueled resentment among nearby residents who are bitter about the loss of the historical character of the area and the lack of affordable options because it is located on the former site of the Cooperative.

Although the city made overtures to historic preservation, several historic properties along Mill Avenue were either demolished or significantly altered by the city in its efforts to redevelop. In other cases, the businesses originally operating out of historic buildings were replaced with new ones, many of them corporate chains. A striking example is that of the Mcdonalds and Hooters that co-occupied the historic Laird and Dines building in the 1990s — Hooters is still there to this day.

While it is clear that the desire on the part of city officials to redevelop the downtown was a major contributing factor, it is important to note that the term “gentrification” does not describe all of the redevelopment that is taking and has taken place in Tempe. Gentrification refers to development that displaces existing residents in favor of wealthier, higher class residents. It does not refer to urbanization in general, although the two are often confounded. However, evidence also indicates that development in Tempe is displacing residents. There is also a measure of concern over building heights and the fate of historic neighborhoods and communities.

Two major decisions on the part of the City of Tempe are contributing to the gentrification of Tempe’s urban core: the installation of the Light Rail and decisions related to Tempe Town Lake, both of which were intended to encourage development in their vicinity and run through the urban core area.

Light Rail

Although cars were of key importance to mid-century development in Tempe’s urban core, by the 1970s this area had lost its status as a transportation hub. All the major thoroughfares that pass through Tempe bypass the core. The Phoenix Light Rail could be viewed as a response to manner in which automobile-centrism had left the downtown area behind. This response would be forced to confront the results of that development, much like the response to Mill Avenue’s decline forced the City to confront its new tenants.

Flooding in the Salt Riverbed in 1980 caused severe damage to multiple bridges that spanned it. According to High Country News, transportation officials were forced to respond by creating an impromptu commuter train route over the river, dubbed the “Sardine Express” by city residents.

A little less than a decade later, a plan to introduce the light rail to the Phoenix area was put on the ballot but defeated. That was just the beginning of attempts to bring the light rail to the Phoenix Metro Area. In 2008, after a raft of sales tax increases were passed and federal funding secured, the light rail opened on a 20-mile stretch between Mesa, Tempe and Phoenix.

The city of Tempe planned a zoning overlay district, the goal of of which was to “encourage appropriate land development and redevelopment that is consistent with the community's focused investment in transit, bicycle and pedestrian infrastructure in certain geographic areas of the City.” Mixed use zoning, those that combine retail, commercial, and residential functions in a single, dense area was emphasized.

Several recent development projects indicate that this model of development has displaced residents living alongside the light rail. The Arizona Republic reports that several motorhome developments have been torn down in favor of newer, far more expensive developments. For example, Pony Acres, an affordable mobile home park near Mcclintock and Apache, built in 1969, was torn down to make way for a multifamily development that charges between $1,520 and $1,825 for a two-bedroom apartment.

Another project planned along the light rail, Park Place, is to replace another mobile home park and two restaurants.

Many of these mobile home parks preserve the memory of Tempe’s former position as a major corridor of motor traffic along the once US 60. Now, the presence of the light rail will shape the future of this corridor.

The impact of the light rail on affordable housing may be more far-reaching than the direct replacement of affordable housing with newer, more expensive, apartments. A 2015 article from Confluence Denver suggests that the installation of light rail transit raises rents generally, indicating that rent increases could also force poorer residents out of neighborhoods in the vicinity, forcing transit ridership down as a result as well.

"No growing city can solve affordability," said Josh Rohmer, a principal of BAE Urban Economics, the firm advising Tempe on its latest Urban Master Overlay Plan. "There aren't a lot of affordable projects in Tempe."

Rio Salado

In 1967, ASU students envisioned a facelift for the river including parks, development and aquatic recreation: the Rio Salado Project. The vision was expansive, encompassing the entire stretch of the Salt River in Phoenix, but the project met limited success. That is, except for in Tempe.

Changes in water usage, resulting from the aforementioned decline of the agricultural economy in Tempe freed up water that could be used for the project. The shifting use of space in Tempe set the conditions by which future changes could be made.

Over the next few decades following the inception of the plan, the Rio Salado Project moved toward completion in 1999, opening only in a small stretch of Tempe. The development would include parks, the Tempe Arts Center and a water park.

The Rio Salado also received its own overlay district in 1981, the purpose of which was to encourage private development and “revitalization” along the shores of the planned Tempe Town Lake complex.

Tempe’s effort to encourage development along the shore of the Town Lake has largely proven to be a success, with luxury apartment buildings constructed, and currently under construction, all along the shore. According to a State Press article published in 2015, residents have complained that the lake holds little value except for those who can afford to live near it.

"There are a couple of things I think have caused the gentrification, which I truly believe has happened in the Maple-Ash area," Tempe City Councilmember Kolby Granville told The State Press. "I think the biggest thing that has done it is the town lake and the revitalization of Mill Avenue."

Development on Tempe Town Lake is analogous to the DC Potomac waterfront, which was intended to draw new business to the blighted area. However, this approach was decried by many residents for primarily serving the needs of wealthier residents and displacing existing residents.

All of the developments along Tempe Town Lake that we could catalog rent well above affordable rates. Some examples include Skywater at Town Lake ($1,693.00 for a two bedroom apartment, at the cheapest), Ten01 ($1,255-$1,610 for a two bedroom apartment) as well as Bridgeview Condos ($500,000-$700,000 for a two-bedroom condo). Several more are planned as well, such as Broadstone Rio Salado, The Pier and Aura at Watermark.

Finally, there are several office complexes abutting the shore of Tempe Town Lake. Two of the most high profile are the Hayden Ferry Lakeside complex and the 2 million square foot Marina Heights complex. Arizona State University was intimately involved with both developments; it sold the land for the latter development and collects rent on the former. In 2017, the Marina Heights complex sold for $900 millions (the Arizona Board of Regents stills owns the land).

A Gentrifying City

The history of urban evolution of Tempe points to some serious questions about future development.

Despite the low rents in absolute terms, the Phoenix metro area ranks as the 9th most unaffordable city for renters because wages are relatively low with respect to rents. In Tempe, despite housing subsidies for the poorest residents, finding a landlord who will accept vouchers, is offering the right amount of rooms and is able to pass building inspections, can be difficult.

More so, existing affordable stock is being torn down in favor of newer apartments and condos. The fact of the matter is that not enough affordable housing exists in Tempe, Granville said..

While Tempe Town Lake and the light rail have had their own unique effects on Tempe, and have modified the city in ways unique to the form and function of existing development, these effects suggest broad implications for the future of Phoenix’s south central neighborhoods, where future light rail extensions and Rio Salado revitalization efforts will cut through some poor black and Hispanic neighborhoods.

If the history of Tempe’s urban core and the effects the Rio Salado and light rail improvements have had in displacing poor, local residents are to be any indication, then the future may see gentrification accelerate in the coming years.

"I think (affordable housing) has gotten worse, and I think it will get worse," Granville said. "But I will tell you that I don't think it was this council that made any of that happen."

Editor’s note: This article was originally published in print in State Press Magazine, vol. 19, issue 2 on Oct. 10, 2018.

Reach the reporter at bjcoope7@asu.edu and follow @bcoop_az on Twitter.

Like The State Press on Facebook and follow @statepress on Twitter.