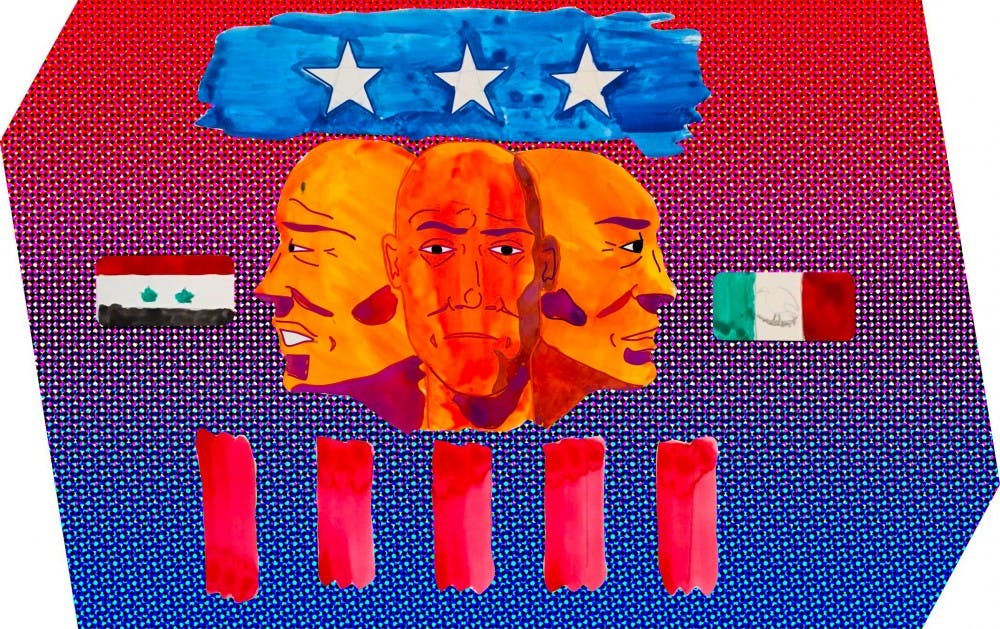

Cultural identity is deeply tied to how individuals place themselves in the world. For the majority of human history, this was a mostly centralized and singular experience, but globalization has created identities of a much more individualized stock.

Although cultural diversity is not unique to American shores, it is supposedly a pillar of our society — a supposed melting pot where your identity goes in and through assimilation becomes just like the rest.

This is contradictory to a nation that is ostensibly tolerant to all, when in practice, we see ethnically singular neighborhoods and tensions about what it really means to be American. As an individual who comes from both Arab and Mexican descent, growing up in a mostly white neighborhood brewed an internal conflict that left me lost as to where exactly I fit in.

I had one foot in each door of my cultural identities, but that left me not wholly a part of any them. The differences were never blatant, but they could be found in awkward silences or laughs.

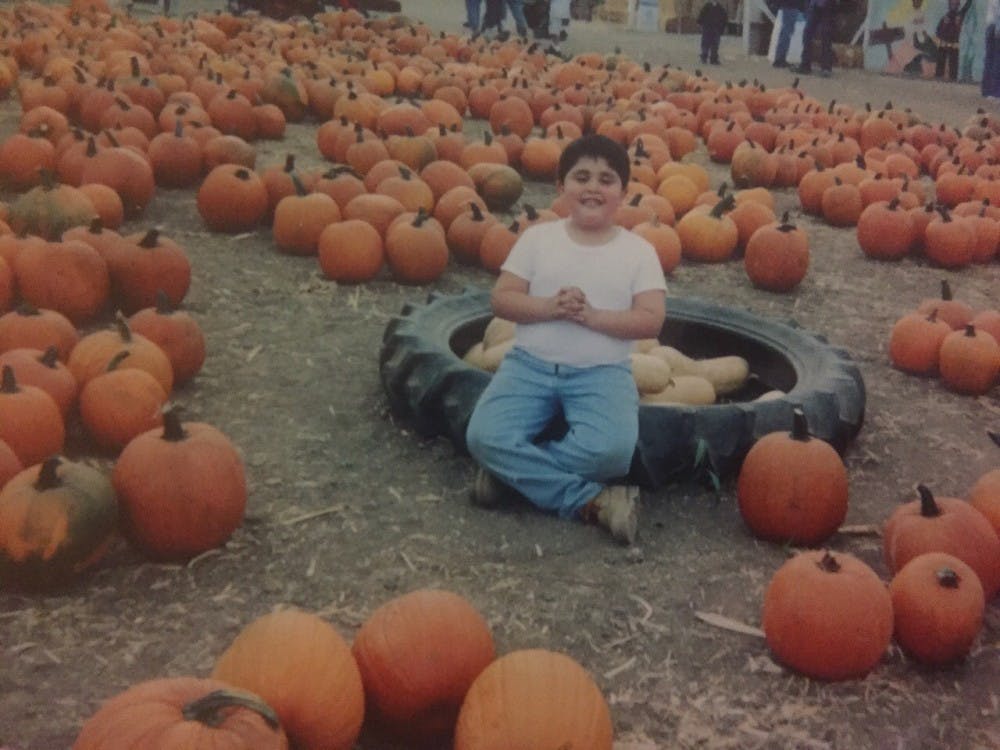

A particular memory stands out when I was at a quinceanera for one of my mother’s relatives. I was about 11 years old, a point in life when dancing consisted of free-form moves garnished with fist pumping.

To most of the other attendees around my age, dancing was more serious. All of them knew the Reggaeton songs to come on and the moves to accompany.

As I lit up the dance floor with my unconsciously abrasive moves, a cousin of mine came up to me and said, “Dude, why are you dancing like that? Are you even Mexican?”

Eleven-year-old me did not know how to react. But that arbitrary comment began the formulation of a poignant other in my mind.

I began to notice more and more differences. I could not speak Spanish as they did, and I was completely oblivious to the subtle cultural nuances that cemented their Mexican identity. For so long I thought of myself as Mexican, and then I realized the gap between our realities and the exclusivity of authenticity.

The space between myself and the Arab community was even further apart. My father immigrated to America when he was only 16, but that was long enough for it to be an integral part of his identity. I was able to pick up his proud demeanor that resonates from the Middle East. I identified as Arab as soon as I formulated my own persona without knowing the full implications of how it would make people identify me as “the other.”

The rift between me and my mostly white peers became especially pointed after 9/11. It’s hard to explain to someone who is not a person of color exactly what this type of discrimination bred into young kids in America feels like. For the most part it is not overt, but rather it manifests itself in small ways that build up over time.

When the substitute teacher mispronounces your name. When people laugh with someone making racist comments about people from your ethnic group — but finishing with, “But not you, Azzam. You’re not like them.”

How you react to these experiences largely dictates how they treat you. You can laugh it off or sweep it under the rug. But your reaction promotes more comments, pigeonholing you until you begin to think of your own culture as something distant. This is the darker side of the process of so-called “Americanization.”

If you react aggressively and try to stifle the comments, you validate their stereotypes and cause hate to fester on both sides. As a teenager, you are dealing with the angst of existing while also fending off thoughts of doubt about the very basis of your identity.

You become scared to bring people to your house so they do not smell the spices your family cooks with, or you shed the religious foundation that your parents gave you, for all the wrong reasons.

The loss of a proudness of self is one that leaves you naked to the woes of the world, especially so when it comes from shedding your cultural roots. Going from the rich traditions handed to you by your parents to trying to fit the mold made by your misconceptions of what an American should be causes a rift in identity that may take years to heal.

I became so enamored with others accepting me that I lost exactly what being “me” meant. I assimilated for assimilation’s sake, taking on the traits I knew my peers would be able to accept. I had always thought of myself as American, so shedding those parts of myself did not feel like a loss at the time.

Only years later, in college, did I come to the realization that those things I felt had ostracized me actually made me special.

Diverse cultural backgrounds are a gift, and though I may never wholly be a part of one culture, I get a taste of lifestyles that most people never do. As someone who is multicultural, I am a bridge for both sides to cross, able to give understanding to my American peers as well as my ethnic brethren struggling to pave their way into an American society.

The idea of America as a melting pot is a false one whose veil is lifted as soon as you live here for a couple years. Neighborhoods are divided by economic class, but even further by race and culture. People stick with what they know, but in this comfortable stagnation, tension is brewed.

In my hometown of Los Angeles, this is easily apparent. Paradoxically, in a land where all are supposedly welcome, a dangerously silent divide is the reality.

Things are not all doom and gloom in this regard, and social consciousness and accountability are becoming the norm — but there is still ways to go.

Instead of celebrating differences as the path towards a true democracy that is representative of all its parts, we have become polarized by movements that do not even have the peoples' interests at heart.

The current climate is not one of acceptance, but one of fear from both sides. Becoming American should not mean giving up your identity in the name of a conformed obedient mass, but rather feeling comfortable enough to be yourself in a way that doesn’t compromise anyone else.

An America bathed in fear is not one anyone wants, and the first step toward a better country is accepting that though people may live differently, it does not mean they are wrong or dangerous.

Editor’s Note: The experiences and opinions presented in this personal narrative are the author’s and do not necessarily imply endorsement from The State Press or its editors.

Reach the reporter at aalmouai@asu.edu or follow @zamurai_96 on Twitter.

Like The State Press on Facebook and follow @statepress on Twitter.