“Bones and cats,” Brenda Baker, who has a doctorate in anthropology, says, holding out her coffee mug decorated with a drawing of a skull made of felines. “These are two of my favorite things.”

Baker is an associate professor at the School of Human Evolution and Social Change (SHESC) and specializes in bioarchaeology, human osteology and paleopathology. She is also the co-editor-in-chief of Bioarchaeology International and recently returned from working on dig sites in Sudan.

While she gathers her data and research from her sites after visiting Sudan, Baker continues her research with several ASU graduate and postgraduate students. In Sudan, Baker examined the remains of ancient ancestors through their bone structures at different geographical sites. She and her students study her findings and record them in the school’s lab.

“I always wanted to get to work in Nubia and started working in earnest and got to Sudan for the first time in 2006,” Baker says. “I went there for a call for help to salvage material from the fourth cataract region because they were building a massive dam. This was going to submerge a huge area and was virtually unknown archaeologically. I got involved with those that needed help particularly in cemetery sites.”

Each piece of bioarchaeology Baker researches in Sudan is part of a giant puzzle as if ancient ancestors had left a story for her research team to piece together.

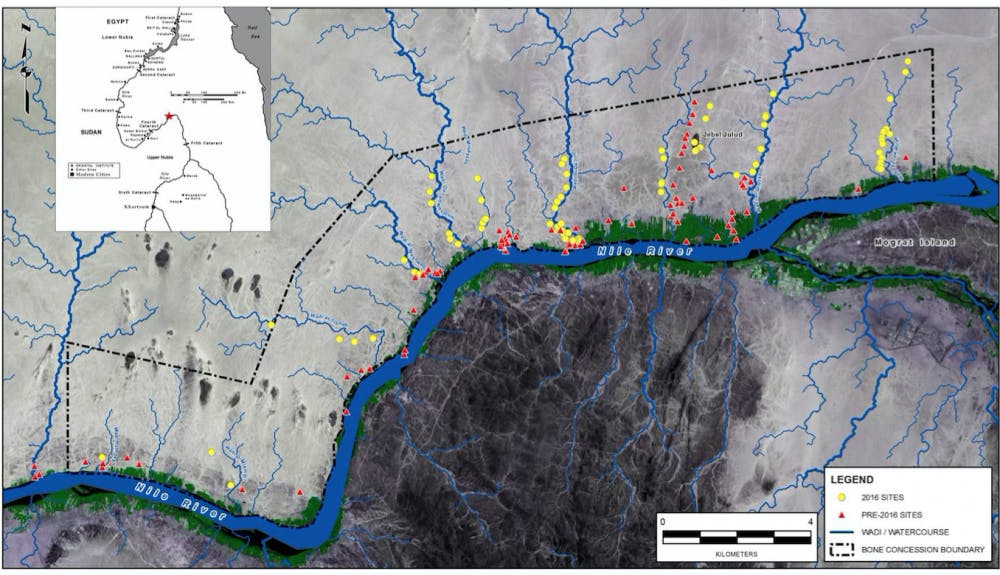

Baker’s research team has recorded and located about 200 sites throughout the course of working in Sudan. Some are a part of Baker’s project titled, Bioarchaeology of Nubia Expedition (BONE) in which different team members use their skills to solve the mystery of each site.

ASU postgraduate student from the University of Toronto, Aleksandra Ksiezak is a member of the expedition provides her expertise on studying pottery.

“Based on the fragments I study and all the ceramic material the field team recovers from the site, I also try to establish the date of when the [ceramic material] was made,” Ksiezak says. “This helps everyone else to assign the proper date of the burial. I am able to establish framework or brackets of each context. I analyze the shape, decoration and manufacture technology.”

Ksiezak solved a part of a puzzle when she figured out one of the women on the site was an immigrant potter.

“[The woman] was an immigrant from the east desert because of the different pottery culture which was never made in the area the field team was studying,” Ksiezak says.

Ksiezak says the way the woman made those pots proved that she grew up somewhere else and arrived in that specific site.

With the help of Baker and her research team, countless stories of ancient ancestors unraveled. Baker described the feeling of seeing these discoveries as being full of “intense emotional swings that hit you” during the excavation.

“You have these mixed emotions in that you’re really excited but you know something like that could happen today very easily,” she says. “You get choked up with these intense emotional swings while excavating the site. These things happen in those villages today with no real health care.”

Of the many stories and ancestors discovered, Baker says finding a skeleton of a mother who experienced a breeched birth. The head of her baby was still in her pelvis.

“You have intense emotional swings when you’re excavating something like that,” Baker says.

ASU postdoctoral research associate Katelyn Bolhofner worked with Baker on her Sudanese skeletal collection excavated from the Ginefab School Site. Both worked on publishing papers on dental avulsion, or the process of teeth wearing down, within those individuals on the site.

“Brenda is the queen of puns,” Bolhofner says. “She works incredibly hard, long hours in the field, but maintains a sense of humor throughout. She is careful and thorough in her research and writing and is an excellent teacher.”

Bolhofner also worked with Baker in Cyprus, where they discovered the earliest known case of leprosy on the island.

“I owe much of my knowledge of osteology and paleopathology to Dr. Baker,” she says. “She gave me many professional opportunities. I am grateful to have had her as a mentor throughout graduate school.”

Baker’s research while working in Sudan was accompanied with learning more about the present culture and surrounding communities as well.

“A lot of people have a misconception in Sudan in that it’s a horrible place and unsafe,” Baker says. “I am located in the northern rural part of Sudan which recently got electricity. People (in Sudan) are so friendly and helpful. We reciprocate help if we saw a vehicle stuck in the sand. We make connections with farther away communities. If you get stranded someone will take you in. It amazes international team members the attitude towards helping people and not just driving by them.”

Baker says creating Bioarchaeology International was daunting, but worth it.

“It’s so different to be able to hold the hard copy,” Baker says. “Just developing a new journal is an awful lot of work. Seeing it being published with other people’s excitement is very rewarding.”

______________________________________________________________________________________________

Reach the reporter at Ashlee.Thomason@asu.edu or follow @ThomasonAshlee on Twitter.

Like The State Press on Facebook and follow @statepress on Twitter.