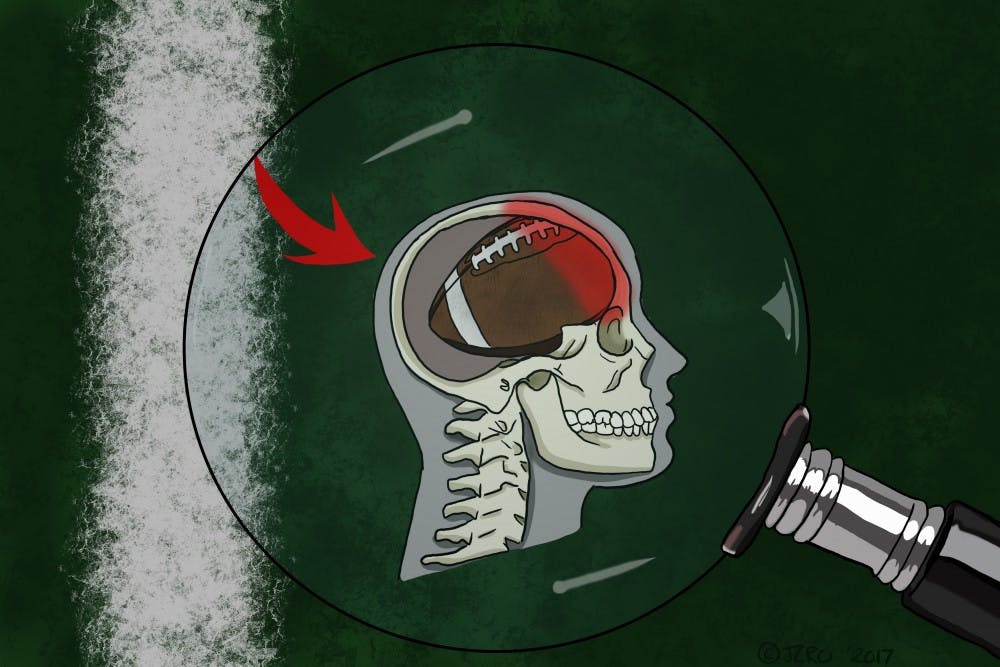

A hit to the head causes a lot more concern than it used to — especially when it happens in sports.

Concussions have been a growing worry in the public eye as more studies on their severity have been researched and publicized.

A recent compilation of data from ASU football players could allow for exciting innovation in the diagnosing and treatment of concussions.

For the past three years, the Translational Genomics Research Institute (TGen) has partnered with ASU and Riddell to collect comprehensive data from ASU football players. The data include measurements of the players’ biofluids and information regarding head impacts, which are obtained through advanced sensory technology in the players’ Riddell helmets.

“We hope these data are a first step to recognizing what a concussion looks like,” said Dr. Kendall Van Keuren-Jenson, TGen associate professor of neurogenomics and co-director of TGen's Center for Noninvasive Diagnostics. “The dataset from the recent publication can be used in any number of studies to compare normal individuals to individuals with different diseases or injuries.”

The dataset, which is the largest of its kind, is made up of extracellular RNAs that, upon further research, could lead to the discovery of biomarkers that can effectively diagnose concussions.

“Our partnership with TGen and the research conducted with these biomarkers will ideally provide doctors, trainers and administrators with a mechanism to proactively safeguard the health of our student-athletes,” said Ray Anderson, ASU's vice president for university athletics, in an interview with TGen.

Not only will this collection of data allow for more research on keeping athletes safe, it also spreads awareness on concussions as a whole.

The severity of concussions was downplayed until studies, like this one, revealed the true extent of the problem in sports, namely football.

As this issue has become more publicized through research in conjunction with player testimonies, lawsuits and box-office hits like "Concussion," the public has become more mindful of concussions in football and other contact sports. Consequently, protective gear and other precautionary measures in such sports have increased over the past few years.

“There is definitely more information available about concussions, and that has helped raise awareness and increase the use of protective gear,” Van Keuren-Jenson said.

In light of criticisms to the NFL’s concussion protocol specifically, new regulations were set into place before the start of the 2016 season, including a rule that prohibits players from staying on the field if they get a concussion. Failure to remove them from the game results in a six-figure team fine and potentially the forfeiture of draft picks.

Concussions are currently detectible mainly through the reporting of symptoms, which athletes often try to dismiss or ignore. High school and college athletes who are trying to impress scouts and recruits may downplay their symptoms for the sake of getting a scholarship or being drafted professionally, whereas professional athletes may do so because they don’t want to be replaced.

There’s also the ever-present mentality of athletes to just play through injuries, and especially where concussions can’t be seen, athletes think they can easily push through them.

Athletes immediately removed from play after #concussion recover faster than those who play thru symptoms. @AANMember @TheAMSSM @NATA_SSATC pic.twitter.com/OXKwpn592e

— Chris Giza (@griz1) March 29, 2017

“Most concussions cannot be diagnosed by imaging, such as a CT scan or an MRI,” Van Keuren-Jenson said. “The injury does not show up, except as symptoms. In those trying to hide a concussion, or in vulnerable populations that may not be able to communicate their symptoms, this can be problematic.”

While unreported concussion symptoms are a huge problem, hopefully as the public grows more educated and aware, players will realize the true necessity of speaking up about their symptoms.

“The protocols around concussions and athletes are changing and improving all of the time,” Van Keuren-Jensen said. “There are fewer practices that involve hitting, the ways that athletes are taught to hit have changed. Yes, things are improving, but they still have a ways to go.”

Reach the columnist at alexwolfe3098@gmail.com or follow @alexandrawolfe_ on Twitter.

Editor’s note: The opinions presented in this column are the author’s and do not imply any endorsement from The State Press or its editors.

Want to join the conversation? Send an email to opiniondesk.statepress@gmail.com. Keep letters under 500 words and be sure to include your university affiliation. Anonymity will not be granted.

Like The State Press on Facebook and follow @statepress on Twitter.