She smiles at her family and the illusion of happiness persuades loved ones that everything is OK. However, sad eyes tell a story of a draining battle within. The darkness fights the light until there is nothing but an outline of a girl that once was.

Screams are left unheard as the darkness begins to suffocate the future and erase happy memories of the past. All feelings are lost until there is nothing but black emptiness, sorrow and pain.

Depression lurks around the corner of approximately 30 million U.S. citizens, according to Deveroux Ferguson, a researcher at the University of Arizona Medical College Phoenix.

Thirty million U.S. citizens lay in the darkness while feeling helpless. Depression engulfs every aspect of their life until they become isolated from loved ones. It remains until someone hears their cry for help, for feeling.

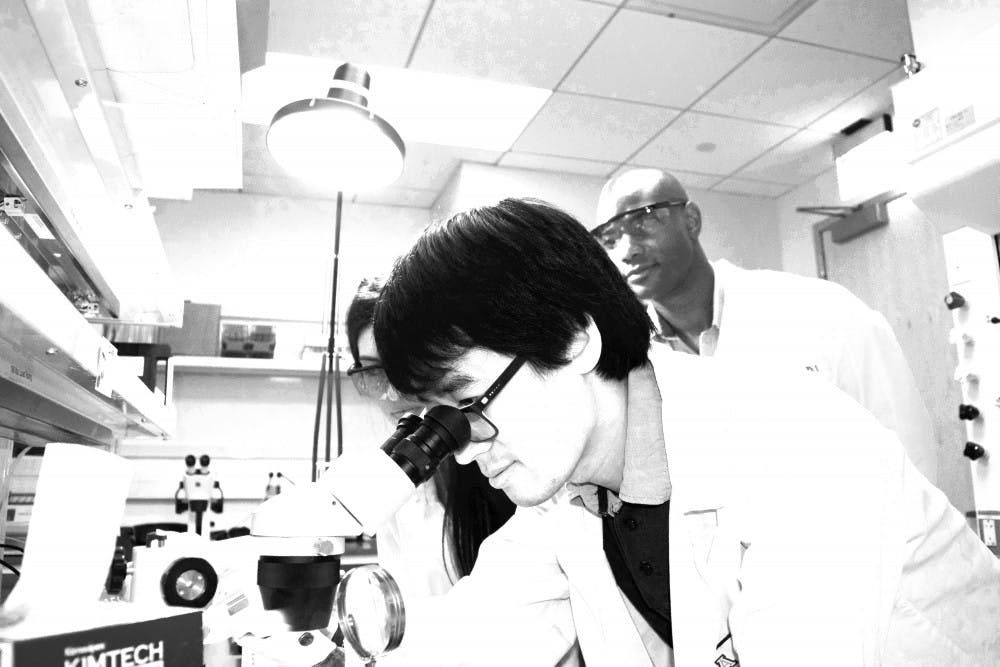

Deveroux Ferguson’s recent discovery could create a new way to treat this depression.

He linked the SIRT1 protein and its impact on certain genes as a key player in major depressive disorders. SIRT1 is a protein that can change the behavior of genes, according to a press release from the U of A College of Medicine Phoenix. It has been found to affect metabolism, development and cancer.

This discovery was made in Ferguson’s lab at the University of Arizona Medical College Phoenix, down the road from the ASU Downtown Phoenix campus. He is also part of Arizona State University's neuroscience interdisciplinary faculty.

He observed mice behavior in accordance with SIRT1 levels. Mice with higher levels of SIRT1, even in the short-term, displayed elevated signs of anxiety and despair, Ferguson explains.

The increase of SIRT1 has been traced to a distinct region of the brain that influences changes in depression or anxiety.

“(The) SIRT1 link to depression is very new and opens the door for the development of novel, more (efficient) antidepressants,” Ferguson says.

Currently, antidepressant medications mainly target monoaminergic pathways, which play a role in the body's process of controlling chemicals like dopamine, serotonin and norepinephrine, Ferguson says. These chemicals are often associated with mood and are altered via antidepressants.

These current treatment approaches for depression are largely ineffective and leave more than 50 percent of patients symptomatic, Ferguson says. Additionally, the U.S. loses about $226 billion annually because of chronic illnesses, like depression, according the the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

More traditional medications take several weeks to months to display benefits. They also include side effects such as nausea, insomnia, fatigue, drowsiness, increased appetite and weight gain, Ferguson says.

“What’s genuinely exciting about the study is that we have identified a potential novel non-monoaminergic signaling pathway to treat depression,” Ferguson says. “You can do the opposite study where as opposed to increasing SIRT1 activity, you can block SIRT1 activity."

Blocking SIRT1 activity results in anti-anxiety and anti-depressive behaviors. This knowledge could be used to create new types of medication to treat depression.

Ferguson says the long-term goal is to determine the difference between animals who are resilient and animals who are susceptible to depression.

Currently at ASU, students with depression meet with a counselor to assess their needs. A plan is then created with the student, says Aaron Krasnow, associate vice president and director of Arizona State University health and counseling services.

“I know that many students have experience with antidepressants prior to college,” Krasnow says. However, each student's plan is different.

Ryan Dietzman is a exercise and wellness sophomore who has struggled with depression since middle school.

"I do not believe current anti-depressants help with depression. I find exercise to be my medicine," Dietzman says.

Emma Natzke is a psychology junior at Arizona State who also battles depression and has never taken anti-depressants.

"Anti-depressants did not help my mother," Natzke says. "However I would be open to trying a new type of anti-depressant."