“Where are you from?” is a dreaded question for many, especially children of immigrants. Due to my appearance, I expect the question to be about where my parents are from. Many times, answering “America,” although being born and raised here, does not seem to suffice. Somehow my parents’ home country overshadows my personal identity. I sometimes get a patronizing, “Wow, you speak English really well!” Even though my Urdu is choppy and I grew up learning and speaking English. This is not to say that where my parents are from does not play into my identity, but I have come to terms with the fact that being a child of an immigrant is an entirely different identity.

I remember hiding the kebab sandwiches my mom would make me in elementary school, because I was embarrassed of the smell. I wanted peanut butter and jelly sandwiches just like my other friends had. In middle school, I was told that the henna on my hand was actually a “rash” by a school instructor, and was immediately sent to the nurse’s office. And while it’s now a very popular trend, it was not that way when I was an 11-year-old kid. A part of me resented my culture, especially when other kids would pry about the weird sandwiches my mom made for me, or when they raised an eyebrow if I told them my favorite movie was "Mohabbatein," a Bollywood film. As I grew up, high school dances and late parties were just not in the equation for me, even though I secretly wanted to go. This was not the case for my parents. While having their own social matters to adjust to, cultural limbo was not one of them.

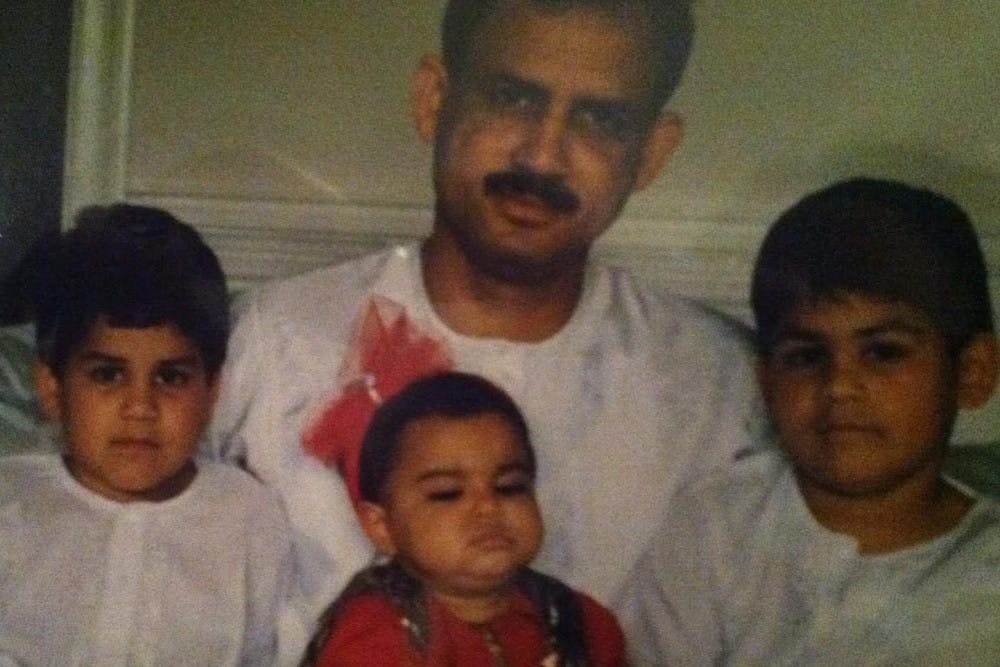

Being that my parents are from Pakistan, I can only really speak from personal experience, but I find that it is crucial for people with immigrant parents to address issues within their specific “hybrid culture,” for lack of better words. A very commonly felt sentiment from first generation kids is feeling neither here nor there, in my case, not fully Pakistani and not fully American.

This can often lead us to really try and assimilate fully into perceived American culture, I say perceived because American culture means different things to different people. This can also lead us to try to compensate for our lack of perceived culture, and really try to hold onto the roots our parents have.

I find that while to each their own, diaspora identity is important. Too often we ignore it and pick one culture to stick to. As a first generation Pakistani, a daughter of immigrants, my identity is new and hard to navigate through. It’s much easier for me to only talk about colonialism in South Asia, or to complain that other Pakistani Americans are “too cultural” or “too religious." The task at hand however, in my opinion, is solidifying our identity as first generation kids, and coming to terms with the fact that paradoxes exist when juxtaposing our parents’ home country to our home country. It is OK to live within them, accept them and, most importantly, talk about them.

Let’s talk about how there is a larger percentage of depressive symptoms within South Asian Americans between the ages 15 and 24, let’s talk about how there is a higher suicide rate in South Asian American women as compared to the general population. Specialists concur that lack of support, awareness and education may contribute to these depressive symptoms. They also say that due to the nature of immigration — building emotional resilience, having a need to assimilate and valuing work ethic above all — can lead to lots of emotional repression, trickling down inevitably to the children of immigrants.

In my community, these issues are simply not addressed. The more time we spend trying to assimilate or compensate, the more repression occurs. I believe more honest dialogue, relevant art and poetry, more representation in the media and less propaganda about immigrants can really help remove the negative stigma of immigrants and anything pertaining to them. By doing this, others are more comfortable to speak about their personal vulnerabilities and identity issues, and only then can the building begin. I hope that more first generation Americans can come together and speak about the mental health concerns they have and the social paradoxes they face, such as dating when their parents are against it, exploring different religious paths and facing gender identity issues when the stigma is even higher in their culture. Being able to talk to understanding peers — rather than being preached to — will really help us confront our identities on an individual level, and in a larger way.

Related links:

ASU student finds success after fleeing Iraq

"I Am from Chile" film screening and conference opens discussion and explores diversity

Reach the columnist at anshakoo@asu.edu or follow @ashak21 on Twitter.

Like The State Press on Facebook and follow @statepress on Twitter.

Editor’s note: The opinions presented in this column are the author’s and do not imply any endorsement from The State Press or its editors.

Want to join the conversation? Send an email to opiniondesk.statepress@gmail.com. Keep letters under 300 words and be sure to include your university affiliation. Anonymity will not be granted.