By 8:30 a.m., he’s making breakfast, pouring his cereal in a bowl and feeling for the carton of eggs in his refrigerator.

He shuffles toward the stove, pours oil in a skillet, feeling around for the front burner knob and making sure the heat is coming through before placing the skillet on the stove.

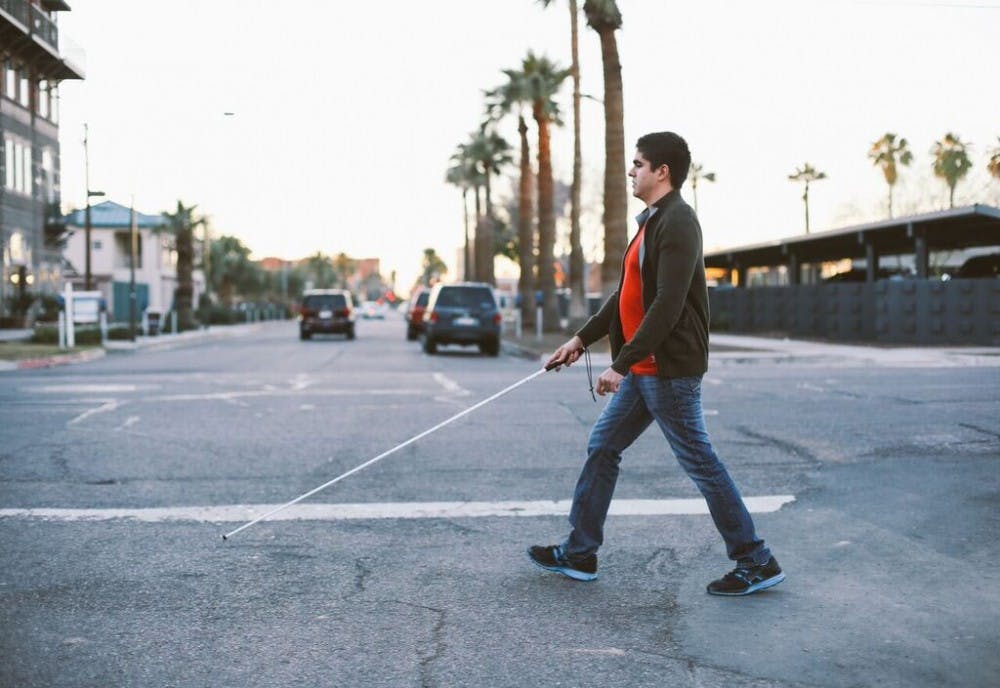

As he heads out the door for class at Arizona State University, Rolando Terrazas grabs his long, white cane behind the front door of his apartment. He makes his way down the hall to the elevator and walks approximately six blocks to class.

Picture yourself cooking or picking out your clothes blindfolded. Imagine not being able to see your favorite television show, know what colors look like or appreciate a sunset.

Those who can see take it for granted, while some spend their entire lives adapting to an everyday routine.

Terrazas will never know the beauty of an Arizona sunset or enjoy the top movie at the box office because the 23-year-old was born blind.

Growing Up

Born and raised in Huatabampo, Sonora, Mexico, Terrazas never expected his blindness to distract others.

He recalls his frustrations as a kid in school, where his peers acted differently around him and labeled him as “the blind kid.”

Terrazas could communicate and walk like anyone else, yet kids didn’t accept him for his physical disability because they didn’t understand it.

“It was tough trying to get them to understand that this was ok, that I was a normal kid just like them,” Terrazas says.

Terrazas was lucky in that he was surrounded by the same group of students through elementary school, so they eventually learned to treat him the same.

Academic Accommodations

Terrazas was introduced to Braille at age 5, allowing him to learn to read and write at the same pace as other students.

Braille is a system of six raised dots that are arranged in cells — used in combination to write letters, numbers and symbols — that can be read by touch. Braille requires heavy paper fastened in a slate and a stylus that allows one to punch holes in the paper from right to left. The paper is then removed from the slate, flipped over and read in the opposite direction.

He took notes in Braille throughout elementary school, but it was difficult for him to receive disabled services because Mexico doesn’t provide a lot of services for the visually impaired, or disabled people in general for that matter.

Terrazas’s mom found a teacher who could teach him Braille, helping him learn math and science. His mom also learned Braille in order to transcribe his notes for teachers.

Education was never an easy feat, and that’s proven to be especially true at the university level. Terrazas transferred to ASU from a community college in spring 2015.

When his professors upload documents to Blackboard or provide handouts, Terrazas doesn’t always have the option to read these in alternative format, such as through a screen reader.

“When they upload a PDF, sometimes there’s an image, and that doesn’t read well with a screen reader,” Terrazas says.

Screen readers are software programs for the blind or visually impaired that interpret the text displayed on the computer screen through a speech synthesizer or Braille display.

“Sometimes that takes longer than I would like it to take, and I can fall behind or I end up using other methods to get the information I need,” Terrazas says. “Sometimes I don’t get everything, so I work with what I have, and that’s a challenge I have on a regular basis with most of my classes — accessibility.”

It can take 15 days to three months for the ASU Disability Resource Center (DRC) to convert a ten-chapter textbook to Braille, taking more time if there’s math or images involved, says DRC employees Retesh Reddy and Boovaragan Kumara Ramanujan.

The most common service used by the 110 active visually impaired or blind students on campus is the alternative format department, where textbooks and handouts are converted to Braille or E-text — textual information available in an electronic format — depending on the student's preferences, according to Disability Access Consultant Stacy Harrington.

Descriptors are used for graphs or images — for example, young woman with short brown hair, sunglasses on top of head.

Harrington says one issue that comes up for students is last-minute assignments. Professors often assign pop quizzes or assignments based on handouts that are due the following day. The DRC asks professors for extensions in these cases because it takes a day or two to convert.

Terrazas says homework takes more effort and time for the visually impaired or blind. For instance, reading a chapter through a screen-reader program, takes one to two hours, but he has to re-listen at least a couple more times.

One multimedia journalism project took him nearly five hours to record and compile the audio into a podcast.

Career Goals

Terrazas’s mom played classical music for him as a baby and took him to piano lessons when he was 4 years old. While he didn’t always enjoy practicing music, he realized his potential and stuck with it. Terrazas eventually learned to play guitar and sing and formed a rock band in high school.

His love for music drove him to develop a curiosity for working in a radio studio and hosting a show.

Terrazas worked for Pascua Yaqui Tribe radio station KPYT-LPFM in Tucson as a volunteer radio announcer, voicing sweepers, station promos and public service announcements.

General Manager Hector Youtsey says the radio station didn’t play “Rock en Español” before Terrazas came on board.

“He built an audience right away with his amazing voice and personality,“ Youtsey says. “I got a lot of compliments from community members about his show and he got plenty of requests on Facebook.”

Youtsey described Terrazas’s voice as stimulating and magnetic, sounding like a seasoned professional, adding that in his 22 years in the industry he had never met someone with such a passion for radio.

When Terrazas moved to Phoenix to study broadcast journalism at ASU, he continued to produce radio segments for the Tucson show from his apartment, where he has two monitor speakers, a soundboard, microphone and laptop.

Entering the Real World

Terrazas graduates in December 2016 with a bachelor’s degree in broadcast journalism, but fear of judgement in the real world based on his disability worries him.

“When you submit a résumé and apply for a job, you might get a couple of calls. But when they meet you, it shocks them completely to see that you’re walking with the cane,” Terrazas says. “Well, how are you going to do the job?”

Terrazas says employers still remain a little hesitant after the initial shock phase, even though they recognize a visually impaired people can be as productive as their sighted peers.

“We’re moving forward,” Terrazas says. “Because of misconceptions, there are lots of blind people with degrees who haven’t been able to find a job, but we are trying to enter more into the mainstream society.”

Youtsey recalls receiving a phone call from human resources when Terraza first completed his paperwork for the radio station, calling him in “hysterics” worried about Terrazas walking back safely by himself.

“Rolando and I got a big laugh out of that,” Youtsey says. “I had no idea he was blind. His handicap didn't have an impact on the interview at all.”

Living Independently

One of the biggest misconceptions of the visually impaired is their inability to live independently, Terrazas says. Sighted people assume the visually impaired need full-time care; someone to cook, clean and do the laundry.

“The majority of people are sighted, so if you’re sighted, then you’re going to use your sight and that’s totally OK,” Terrazas says. “But if you don’t have your sight, you have to come up with alternative techniques. It’s just a matter of adapting.”

Terrazas added that he certainly can cook for himself — he just chooses not to.

He’s never burned himself badly or gotten sick from anything he’s cooked. He uses his senses of touch, taste and smell to tell when food is done, just like sighted people.

Terrazas uses a Braille labeler to identify the microwave and oven buttons, stove-top burners, and washer and dryer options. He knows the smell and shape of a Lysol can and uses bleach to clean his shower, sinks and toilet.

Steve Patten, Terrazas’s cane traveling instructor at the Colorado Center for the Blind (CCB), says if one wants to live independently they should live in a truly metropolitan city, somewhere with public transportation, ample housing and a walkable distance to a variety of services such as grocery stores, gyms and restaurants.

“If you want to be independent, you have to be independent 100 percent,” Terrazas says.

Mobility

The visually impaired or blind often use canes or service animals to move around. Terrazas was taught to use cardinal directions when traveling with his cane.

Patten says that clues like “the sun rises in the east” are also helpful in knowing which direction one’s traveling.

One myth that’s not always ideal is counting steps. While it’s helpful to understand a building’s general location, Terrazas also listens to which way traffic is going when approaching a crosswalk. If he’s at all unsure about the traffic, he waits until the next round.

Terrazas says he knows people stare at him while crossing the street.

“A lot of people think — when they see a blind person walking down the sidewalk or crossing the street — we don’t know where we’re going or we’re not aware of our surroundings, even though I look confident,” Terrazas says.

Terrazas studied cane traveling at age 6 as part of a summer program at the Foundation for Blind Children. He was never afraid of falling or running into things.

Even so, cane traveling allowed him to feel more independent because he doesn’t have to rely on holding onto someone when climbing stairs or going to new places.

Terrazas uses Google Maps or a GPS if he’s going somewhere new, asks someone where the door is or listens to where most people are coming from when approaching his destination.

“You need a lot of patience when finding something for the first time,” Terrazas says.

He uses a GPS to walk to the grocery store alone for the first time, understanding the address numbers in order to determine which side of the street the store was on. He knows he is close once he hears the sound of shopping carts.

Once inside a store, Terrazas often seeks customer assistance. He says they usually want to grab him to take him directly, but he doesn’t like that. Terrazas instead prefers to follow the person, sometimes asking for a shopper’s assistant to help choose groceries which is quicker when preparing a grocery list beforehand.

Terrazas spent time at CCB in the summer of 2015 alongside Patten, who is also blind since birth, and taught cane traveling basics and independent living skills to fellow visually impaired students.

“The biggest misconception is the lack of expectation and the lack of confidence that people have with anyone with a disability,” Patten says. “There’s a lot of assumption that we’re incapable of a lot of things.”

“If one focuses on the most positive aspects of one’s own person, all limitations will get smaller and smaller as we go forward in life,” Terrazas says.