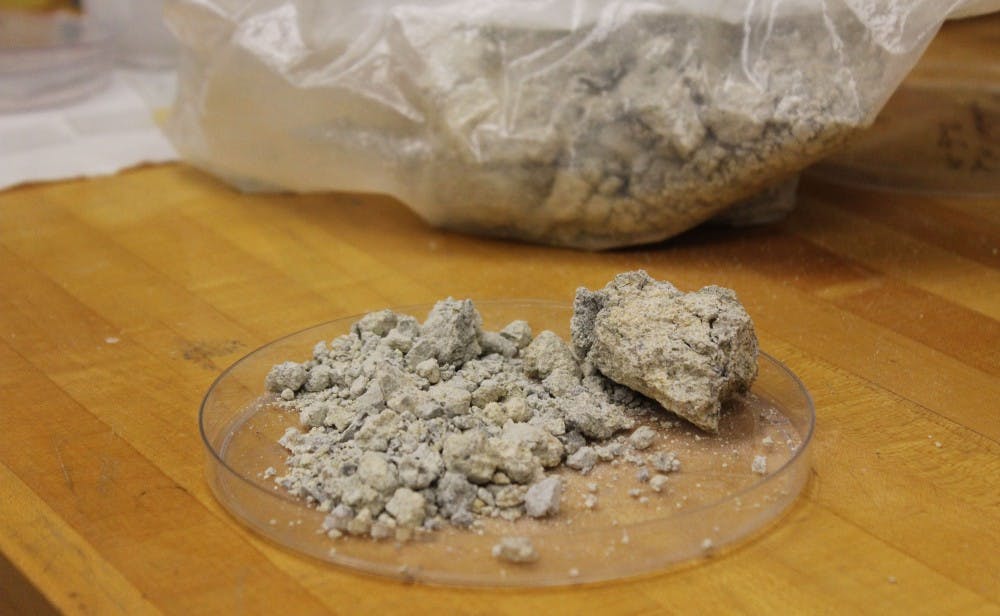

Could a spoon full of clay help the medicine go down? This January, a team of ASU researchers discovered the long-unknown mystery of the medicinal qualities found in certain types of clay.

Recorded as an ancient remedy as far back as Ancient Mesopotamia, some types of clay have medicinal qualities. Now, in present day, clay is used to treat illness.

Tenured ASU geologist Lynda Williams said previous research involving clay and its healing effects with skin diseases were a big part of their research.

“In 2002, Line Brunet de Courssou had been treating people in Africa for Buruli Ulcers,” Williams said. “She had treated them with French green clay (on their skin), and it would heal after around 100 days.”

Whether clay worked wasn’t the question. Microbiology professor Rajeev Misra, who is involved on the team, said what makes clay effective is what the team wanted to discover.

“We know that the clays release metal and that some clays significantly lower the pH (balance) of bacterial cells,” Misra said. “We needed to know what the mechanism is and how exactly this happens.”

Misra said the team found that certain clays’ antibacterial qualities come from a sophisticated system that involves aluminum and iron.

“Aluminum stays on the surface and causes damage to the envelope,” Misra said. “And then you have ferrous that’s going inside the cell, and causing damage from within it. The cells really have no escape.”

The team’s study shows that this treatment can be more effective than typical antibiotics. Rather than targeting a specific disease, the clay will simply kill bacteria.

Through testing, the team found that this clay is capable of killing antibiotic resistant bacteria. The Blue Oregon clay the team worked with has shown 100 percent effectiveness against salmonella and multiple strains of E. Coli.

However, though external use on skin infections is helpful, as in the case of ulcers, Williams said ingestion is still a bit risky.

“If you want to eat this clay, then you’re going to kill all the good bacteria in your body too,” Williams said. “Along with that, these are also massive sulfide deposits. They’re associated with mercury and arsenic. Clays are too variable from one site to another to use on a large scale taken internally.”

California-based grad student Keith Morrison, who was a key member of the research team, said he thinks the next move would be to manipulate the deposits.

“The next step forward would be to make synthetic mixes to mimic the natural deposits," he said. “It can be too variable to use a natural deposit. When we make a synthetic mix, we can have more control.”

Related Links:

ASU to acquire $3.7 million research instrument

Editor's note: A previous version of this article included a video that referenced work by another scientist at ASU. Her work is not connected to the work being discussed in this article. The video has been removed.

Reach the reporter at Ethan.Millman@asu.edu or follow @Millmania1 on Twitter.

Like The State Press on Facebook and follow @statepress on Twitter.