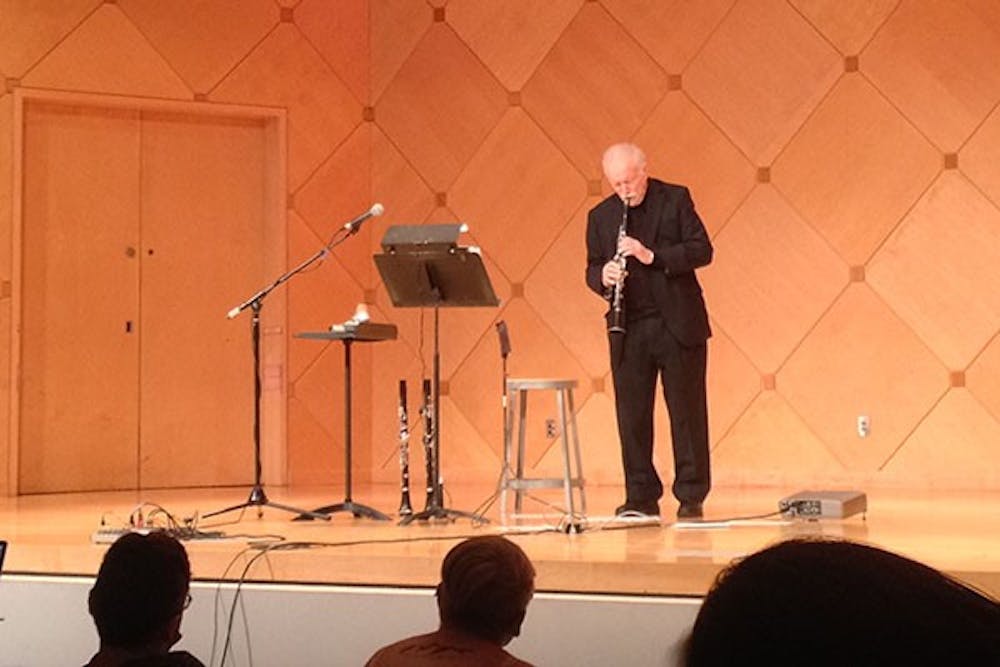

(Photo Courtesy of Joshua Gardner)

(Photo Courtesy of Joshua Gardner)At 88 years old, William Smith still loves to go to Cold Stone Creamery to get a scoop of vanilla with M&M’s. This is exactly what he did on Saturday, when he sat and talked to ASU’s clarinet studio about his vast array of experiences, ranging from playing for the Reagans to Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev. Then Smith realized his ice cream was melting and paused to eat it.

He is the inventor of many extended techniques for the clarinet, including playing two clarinets at once, playing half a clarinet, and experimenting with playing multiple notes at once, called multiphonics. But he keeps coming back to ASU for the ice cream, he said.

Smith visited ASU Friday through Sunday to perform a recital of his work, teach a master class, and share his stories with the clarinet studio. Although it is his fourth visit, he said he doesn’t tire of visiting because of the warm, inventive nature of those in the clarinet studio under professors Robert Spring and Joshua Gardner.

“Many clarinet teachers at universities are trying to prepare you for playing in a symphony orchestra, but in addition, we need to keep up with what’s happening with the music of our day,” Smith said. “(Spring) seems to infuse his students with curiosity for new things. It's always a pleasure for me to play for the students here. (Spring) is a good host and a good man and he knows this great ice cream place.”

Smith’s career as a world-famous clarinetist began when he was 10 and a traveling salesman came to his parents’ apartment.

“(The salesman) said, ‘Every home should have a musician, and if you'll pay for 32 lessons for your son, we’ll give him a free instrument,’” Smith explained. “I was standing there, and I said, ‘Please Mother, can I?’ … I did well in the clarinet and loved it from the beginning.”

When he was 13, he attended the 1939 World’s Fair and saw Benny Goodman perform, which inspired him greatly.

“Hearing him was like opening the doors of paradise,” Smith said. “I thought, ‘That’s what I want to do.’”

At 15, he auditioned and was invited to join the Oakland Symphony. After high school, he decided to follow the lifestyle of his idol, Goodman, and joined a touring dance band. But after hearing some advice from a drummer in the band, Smith decided to focus on his education and briefly attended the Juilliard School, where he performed at Carnegie Hall.

He then he decided he wanted to compose, so he left Juilliard and returned to Oakland to study under the famous composer Darius Milhaud, who Smith said taught him some of his greatest lessons in composing.

“It’s not just a numbers game," he said. "You have to make music out of it."

Smith’s composing career, both for classical and jazz clarinet, as well as his performance skill, led him to many famous venues and people, including concerts at the White House and the Kremlin.

Smith said during the band's photo-op with the Reagans, the band's manager tried to convince Nancy Reagan to invite the musicians to perform at a dinner conference in Moscow for Gorbachev. The manager succeeded, and the quartet flew to Russia on Air Force One.

He said the trip wasn't as glamorous as most would think.

“They had us sleeping on wooden benches and eating peanut butter sandwiches," Smith said. "It was no big deal."

After the Moscow concert, Gorbachev approached Smith to shake his hand and congratulate him on the performance.

"I thought I did my little bit to help tear down the Berlin Wall," Smith said.

He said his type of experimental techniques for the clarinet support his general philosophy about music.

“Music will die if you don’t refresh it,” Smith said. “I think you should explore what the clarinet can do, beyond just the normal symphonic sound.”

Kristi Hanno, a clarinet performance graduate student, said she greatly admires all Smith has done for the clarinet community through his unique compositions.

“I like that he stuck his foot out there for us,” she said. “It opens up so many doors compositionally and performance-wise. With those basic building blocks that he discovered, there’s a whole world waiting for us.”

Hanno said she loves talking to Smith because his stories and wisdom are inspiring.

“I’d like to get more involved with composition for contemporary clarinet,” she said. “He’s just a wealth of knowledge.”

Robert Spring, who teaches clarinet, went even further to say Smith is responsible for nearly all recent changes in clarinet music.

“Bill changed the direction of clarinet playing,” he said. “I think Bill’s responsible, in many ways, for everything that’s changed in clarinet performance since the 1960s. I think he's responsible for quarter tones, using electronics in performances and giving composers the OK to expand the palate of musical sounds out further.”

Quarter tones are another extended technique in which a note is played which is halfway between the normal interval for different notes to exist, which is a half step.

Spring went on to say Smith isn’t just an excellent musician but is also a genuinely kind person whom he loves to see interact with his studio.

“Bill’s a very giving person, both with his time and his talents,” he said. “Bill encourages everyone to be as creative as he is, and he challenges you if you're not.”

While introducing Smith before his recital on Saturday, Spring cut short his prepared speech after he was choked up by tears.

He said Smith’s impact on his life, also as a world-famous clarinetist, is immeasurable.

“That’s why I get so emotional, because this man has had such an impact on my life,” Spring said. "When he comes here, he doesn't speak loudly, but he manages to command a room and I don’t know how he does it, except for what he’s done.”

Smith finished eating his ice cream and sat contently, speaking to the clarinet students. Just a few hours before, when Smith finished playing in his recital after an encore, he had held his clarinet up over his head, in satisfaction with his performance. The audience had laughed, and the applause surged ever louder.

Reach the reporter at elmahone@asu.edu or follow her on Twitter @mahoneysthename