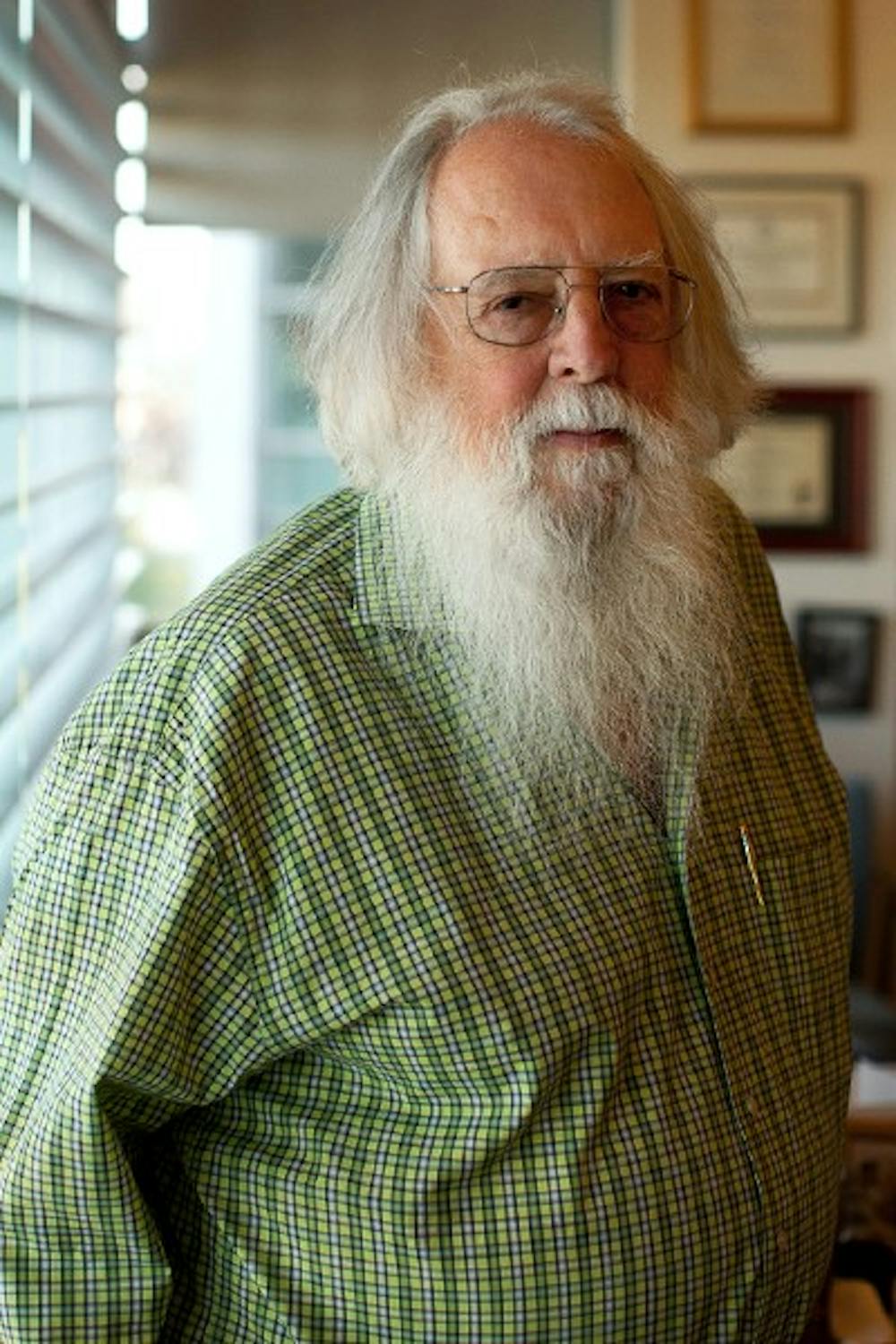

ASU scientist Roy Curtiss has been selected as the 2014 recipient of the Lifetime Achievement Award from the American Society for Microbiology. (Photo by Ryan Liu)

ASU scientist Roy Curtiss has been selected as the 2014 recipient of the Lifetime Achievement Award from the American Society for Microbiology. (Photo by Ryan Liu)

As a geneticist, professor of life sciences, microbiologist and even a soccer coach, Roy Curtiss III has worn many hats throughout his lifetime.

Having a profound impact in the world of microbiology, Curtiss has been selected as a 2014 recipient of the Lifetime Achievement Award from the American Society for Microbiology.

ASM is the largest single life science membership organization with nearly 40,000 members. Its mission is to advance microbial sciences as a tool for understanding life sciences and apply its knowledge and research in order to benefit society.

Winners of the Lifetime Achievement Award are chosen from a very small and select group. Some years, a winner isn't even chosen. Curtiss is only the 20th recipient to receive the award. ASM awards are granted at the discretion of an award selection committee.

Yale professor Daniel DiMaio, a chair of the ASM Lifetime Achievement Award Selection Committee, said 12 to 15 people get nominated for the award every year.

“The nomination includes a summary about their achievements and a copy of their CV,” he said. “We try to look at their lifetime contributions in not just science but overall.”

DiMaio said all the nominees are impressive people.

“Even the people who don’t win have fantastic careers," he said. "Some people are nominated twice. Curtiss made many important contributions and has an outstanding training record.”

Curtiss said he never expected he would receive this kind of recognition.

“I never dreamed I’d get this award,” he said, “The interesting thing is that I have either met or (have) been friends with or very well acquainted with the 19 other people who’ve received the award before. I could even give a mini talk on what each one has contributed to science and microbiology.”

Award recipients receive a cash prize of $20,000, a commemorative piece and travel to Boston for theASM General Meeting where the laureate presents the award.

Multiple areas of research

Curtiss said he remembers being on crutches for most of high school because of sports injuries.

“One of my teachers told me I should give up and just stick to science,” he said.

Curtiss earned his bachelor's degree from Cornell Universityand his Ph.D. from theUniversity of Chicago. At Cornell, he was a member of the Quill and Dagger society, a senior honor society at the university.

Curtiss said he sometimes likes to tease ASU President Michael Crow, who was once an executive vice provost at Columbia University, about how he was there first. Curtiss was born in New York.

“I tell him, ‘I beat him there; I was born there,’” he said.

Curtiss said during one’s lifetime, science always changes. Every year, new opportunities arise.

“Some years ago I used to study how pathogens cause disease,” he said. “I obtained the answers, so I began to realize that I need to use that information to maybe prevent disease. I became very interested in devising new ways in developing vaccines that could prevent infectious diseases in humans and also in animals.”

Preventing diseases has increasingly become the focus of Curtiss’s research. He said microbes account for 35 to 40 percent of all human deaths every year. However, Curtiss wasn't always interested in microbiology.

“In fact, I consider myself a geneticist,” he said. “I only started to work with bacteria and microorganisms after I graduated from college. I never took a course in microbiology.”

Curtiss said he has never remained focused on just one area and jumped around multiple research initiatives.

He was a leader at the start of the recombinant DNA era, which was an explosion of new techniques that enabled scientists to combine genes from different sources.

Curtiss also helped develop safe E. coli strains that could be used for gene cloning and uncovered new aspects of bacterial pathogenesis. He used that information to develop attenuated salmonella-based vaccines that are effective against various forms of human pathogens.

“As scientists, I don’t know if we are fickle, but we get interested in other things,” he said.

A few years ago, Curtiss had the opportunity to use his skills in microbiology to modify photosynthetic microorganisms to produce biofuels.

This work includes designing and constructing cyanobacterial strains to both maximize production of biofuels and biofuel precursors as well as possess the ability to produce energy in an efficient manner.

“I became very excited about the possibility and began working right away,” he said. “I’ve had some successes, some would even say breakthroughs.”

The U.S. government, which hasn't had a consistent policy to support research in biofuels, stopped funding a lot of the research initiatives.

“I don’t know if there is any way that we scientists can get those political wizards in Washington or elsewhere to think long-term,” Curtiss said. “Many of us in science would like to do what we want, but on the other hand, we have to be realistic and contribute to society in some way.”

Impact on ASU

Curtiss said the Biodesign Institute was one of the major factors that brought him to ASU. He was at the Academy of Science, St. Louis when Charles Arntzen from the Biodesign Institute, which was then called AZ-Bio, called him.

“He told me, ‘Roy, you’ve been in St. Louis for too long. Isn’t it time you do something new?’” he said.

Arntzen told Curtiss the plans for the facility and how they wanted to develop a center that would focus on infectious disease agents.

“I made the decision to come here before I was even hired,” Curtiss said. “I got really excited about being in a place where all these opportunities are all available under one roof.”

While at ASU, Curtiss has led an international research project which aims to design a new vaccine for infants to combat pneumonia. The vaccine is meant to be administered without the use of needles.

Pneumonia is one of the leading causes of death in the developing world. The oral vaccine against bacterial pneumonia will combat the disease and outperform injectable vaccines. The initiative has advanced past preliminary studies and is now moving toward human trials.

These new vaccines have proven to stimulate a powerful response in the immune system, making it possible to potentially use them against other diseases like inflammatory bowel disease, Crohn’s disease and even certain types of cancers.

ASU is Curtiss’s ninth institution, and he still has multiple projects underway.

“I’ve been here nine years now,” he said. “Some people say next year is a pivotal year, so what am I going to do my 10th year? Go to the moon?”

Curtiss said that academically, he’d like to say he runs as fast as anyone.

“I like to give everyone a race,” he said.

Research professor Wei Kong said when she was first introduced to Curtiss, she was told he was a big guy with a big heart.

Curtiss and Kong have been working together for 14 years. Kong and others in Curtiss’s lab have collaborated to develop a protective antigen and DNA vaccine delivery platform that uses self-destructing Salmonellafor the prevention and treatment of infectious as well as non-infectious diseases.

Kong said she has always called Curtiss an open book.

“Others call him a moving library because he knows everything,” she said. "So far, every time I’ve asked him a question, I always get an answer, sometimes multiple answers.”

Research professor Melha Mellata has also worked closely with Curtiss. Her research is mainly centered on field bacterial pathogenesis and vaccine development. She completed her postdoctoral training with Curtiss.

“Since becoming an independent researcher, Roy is involved in my projects as my research advisor,” she said. “My projects with Roy include understanding the virulence of E. coli that cause intestinal infections.”

She said she has learned a lot from Curtiss.

“Roy always tells us, ‘Money doesn’t grow on trees, so you should learn how to get it,’” she said. “I wrote grant proposals that were successful while I was still a post-doc in his lab.”

Mellata said a lot of his trainees are trying to follow in Curtiss’s footsteps.

“Even after many years working with Roy, I feel I still have more to learn from him because of his long experience in science and life,” she said. “I feel so lucky to be mentored by Roy, who is an icon in the microbiology or vaccine development fields.”

Mellata said Curtiss was a valuable part of her development as a scientist and gave her the chance to do some of her post-doctoral training in his lab.

“He inspired me to work hard and encouraged me to be independent investigator and he supported me in the development of my own research,” she said. “He always challenges me to take my science to the next level.”

Reach the reporter at kgrega@asu.edu or follow her on twitter @kelciegrega