Imagine an ordinary car pulling up beside an waiting pedestrian. The pedestrian's reflection recedes as the window sinks into the door. A fist is produced from the passenger side of the car. Instinctively, the person, revealed to be a customer, returns the fist bump. This turns out to be a type of social currency, for when the driver's hand retracts, he says an assuaging phrase:

"Get in."

This car wears a bright pink, comically oversized mustache attached to the grill. Perhaps you've seen one of these vehicles, an otherwise average car on an Arizona street, pass you, out of the corner of your eye while in traffic. Believe it or not, they may be the future of transportation in Phoenix.

The way of the future

This fleet of cars, entirely using smartphone technology as the intermediary present, offers a new twist on traditional taxi services. This new business model, instead of relying upon a pack of identical taxis, outsources the two components to the employee using a completely digital model with an app and inputted credit card information setting the pickup place, time and destination, as well as the transaction of money for the exchange of services.

This all occurs before the customer steps into the car. Credit-card readers exist in regular taxis, yet they're more inconsistent when they function, according to local Phoenix RubyRide founder Jeff Ericson.

"Even today, if you get into a regular taxi and if you try to pay by credit card, the driver is likely to tell you that the credit card swipe is broken," Ericson says.

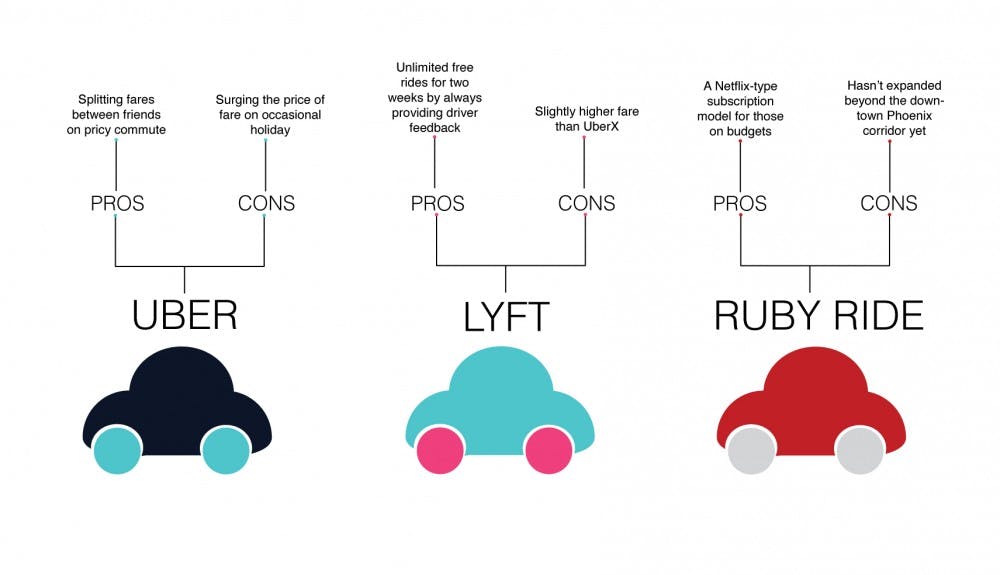

This is an idea that made a foothold in only in the last several years. In 2012, Lyft, the company behind the peculiar mustaches, launched their service in San Francisco. They weren't the first, however, as their nearest competitor, Uber, launched their peer-to-peer taxi service three years prior. Lyft and UberX, a fleet of lush, black taxis, attract potential customers with advertising prices that are 20 to 30 percent cheaper than typical taxi services.

Starting with the inclusion of Valley Metro's lightrail service in 2008, the surge of diverging transportation has attracted the likes of these ride-sharing services, meant to capitalize on new options for passengers. For their part in the Phoenix metropolitan market, Lyft and Uber each employ a couple hundred cars, while the latter says that they have close to the mid-to-high hundreds.

"The Phoenix region has made great strides in advancing transportation alternatives, including expanded public transportation options, light rail and now bike-sharing programs, which contributed to our decision to launch there in September," says Paige Thelen, a public relations specialist for Lyft.

Both companies are relatively new ventures, coming to the Phoenix metropolitan area within the last year. The principal difference between the two is purely cosmetic: Cars used by Lyft have an oversized pink mustache on the grill of newer, yet not uniform automobiles, whereas Uber services their fares in a fleet of sleek, black cars.

For Uber and Lyft, their ride-sharing services operate within radically different business parameters: Instead of a shift supervisor who would normally determine when an employee would work, this responsibility falls to the drivers or "independent operators" themselves, who choose their own driving hours.

Because of the complete autonomy, the professions of Uber drivers usually fall within law and medical students, as well as the underemployed, trying to earn extra income. It is a demographic they hope to see more of since they recently lowered the minimum driving age to 21 years old for all their operators.

The Taming of the Shrew

Needless to say, the program of community ride sharing is still an idea that the government is trying to find ways to address, either due to pressure from existing taxi services or concerns from local government about lack of regulation for these "independent operators."

When bringing ride-sharing services to large cities, like Phoenix, the new models of taxi operators disrupt the business cycle for traditional outlets that local government has tried to monitor and regulate with varying degrees.

"Obviously, new technology and innovation is very disruptive, so whenever we move or evaluate whether to enter a new state, we look and see how business friendly they are, if they are open to innovation, do they welcome new businesses coming in?" Steve Thompson, the general manager for Uber's Phoenix operation, says. "I've lived in Arizona for the past 15 years and it's always been very welcoming, that's why I knew it was smart to bring it here."

The various municipalities with services like Lyft and Uber are responding in different ways to the vacuum being filled by them, depending on the city and politics that govern it. Recently, Seattle's city council voted to limit the number of drivers operating to 150 operators within in the city at once.

At the state legislature in Arizona, the tones of regulation are far more muted and business friendly. Recently, a House Bill 2273 successfully passed the Senate Committee on Commerce, Military and Energy, which aimed to "better define" the concept of ride sharing in the state. If enacted into law, the bill would require a vehicle inspection, background checks (which ride-sharing services already do) and a million dollar insurance policy.

Yet, the legislation leaves room for future finagling, especially in the insurance policy that requires drivers to carry insurance only when they're on clock and not.

Almost simultaneously with the Phoenix measure, lawmakers in Chicago introduced legislation that, in addition to commercial insurance, required drivers to apply for other licenses and set rates.

"Go ahead and click your heels together, mister!"

If local developments in ride-sharing are any indication, the concept itself isn't a stationary one and likely to evolve, something that local architect-turned-entrepreneur Jeff Ericson found in the idea for his company. One day he had the thought that all forms of transportation were the "life of cities," and without it life would come to halt. This thought further bolstered itself during market research when he discovered that beside being on budgets, people use their cars infrequently, mostly for errands about town.

"People don't know how much money they're spending on their own car, so that's where our model makes sense," Ericson says. "Most people use their car about five percent of the time, three percent is the national average. You still get as much access to the car as you did before, but we take care of managing the hassles." Even the name of Ericson's service "RubyRide," a name meant to denote Dorothy's red slippers from "The Wizard of Oz," is designed to describe the service he provides to a tee: friendly faces, in matching red polos, whose job it is to ferry you from A to B with no fuss.

For those people who can't afford the lower rates of a car service, Ericson built his service around a a monthly Netflix-type subscription model, a unique idea for a business model that surprised him because no current taxi service, to his knowledge, used it.

It's too early to judge RubyRide's overall success with the subscription model since they only started taking fares in January and experienced beta-testing previously in the fall. Even Ericson admits that he has done little-to-no publicity for the company, save for an upcoming press show. Their fleet only features six cars now servicing the downtown Phoenix corridor, which they'll expand to Tempe and Scottsdale, at a rate of adding two company-owned cars per month.

Up here, the air is rarified Aside from providing transportation in the modern, digital era, the unifying factor for the companies, which exist below the surface, is to furnish comfort and relaxation to the tedium of snowbirds, traffic and other frustrations, with someone else doing the heavy lifting. For Lyft, passengers can take photos with the pink mustache on their drivers car and interact with the driver on drives. In Uber's case, they're the road guard against earning one of Arizona's tough DUI sentences.

"Students are realizing, 'I don't need to buy a car or I don't need $800 for a parking pass,' and it's way more convenient than getting on a bus and waiting 45 minutes," Thompson says.

When the RubyRide founder offered his take on where his company fits into ride sharing in Phoenix metropolitan area, he echoed Thompson's remarks. "That's the part I like most. It encourages people to get out and experience the city more, you know, take advantage of the cool things that are out there, without worrying about finding a place to park, we can just drop them off and pick them up later," Ericson says. Reach the reporter at tccoste1@asu.edu or follow him on Twitter @TaylorFromPhx.