(Graphic by Diana Lustig)

(Graphic by Diana Lustig)When anthropology graduate student Andrew Seidel was in the third grade, he discovered his love for archaeology while digging up the foundation of an old building that was buried under the playground of his elementary school.

It wasn’t until years later, however, when he excavated his first set of human remains during an internship at the Cleveland Museum of Natural History that he stumbled upon his real passion.

During his free time, Seidel works with Laura Fulginiti at the Maricopa County Forensic Science Center to help identify skeletonized or otherwise unrecognizable human remains.

“I’m being trained pretty much better than anyone in the country right now,” Seidel said. “Even people who are getting their doctorate specifically in forensic anthropology are not seeing as many cases as I am. So I am exceptionally lucky that she has taken me under her wing.”

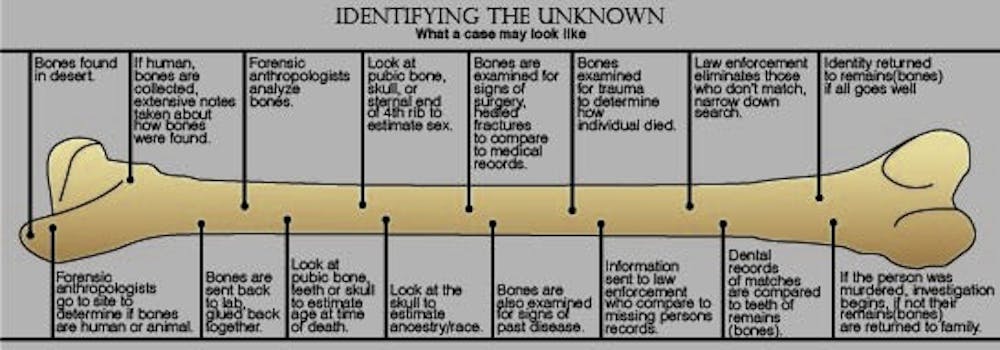

During a typical day working with Fulginiti at the Maricopa County Medical Examiner's Office, Seidel works mainly on biological profiles. This means that when a set of remains comes in that police can’t identify, they look over the remains to find approximate age, sex and ancestry of the individual.

“We give that information to law enforcement,” he said. “Even if we only give them sex, that eliminates half of the missing person’s files. That helps them to be able to sequentially narrow their missing person’s files and match a person from there.”

Their work acts as a guide for the police, Seidel said. Then the police use other evidence and dental records to make a positive match.

“We have to figure out who we think it is before we get the dental records,” he said.

Seidel has been volunteering his time at the medical examiner’s office for the past three years, and it does take a toll.

“It’s a hard job,” he said. “And I think a lot of people don’t realize that. There’s a lot of glamor attached to forensic anthropology – and it is cool. I like it. It’s fun. But it’s a hard job. There’s a lot of stuff that you see that nobody else sees.”

Emotional Toll

Seidel works on remains found in Maricopa County that can't be identified for some reason. These remains can belong to individuals who were burned, murdered, in a car accident or got lost hiking in the desert and have no identification.

“It really opens your eyes to a lot of unpleasant things that are out there that you aren’t really aware of, and how you choose to deal with that is your individual decision,” Seidel said.

Seidel said the situations he is exposed to often cause him to detach emotionally.

“Sometimes you build up a little bit of a wall," he said. "Or you don’t really connect with people that well anymore because you’ve seen things that they haven’t and that you can’t talk to them about. Or even if you do talk to them about it, they won’t understand it.“

Seidel said he likes to focus on people being nice to each other. It helps to balance all the things that he sees that aren’t nice.

“You never know what it’s going to be that sets you off,” he said, “You develop a tolerance. You’re like, ‘Oh, it’s another blunt force trauma case,’ and it doesn’t faze you at all. And it should, right? This is a brutal act that ended somebody else’s life and in a very violent way. That should affect you."

While many things don't faze Seidel, he said sometimes a case will be especially difficult.

"Then maybe you see a scene photo or maybe it’s something specific about that victim, and suddenly one of those cases gets through all of your defenses, and you’re a wreck for a couple days," he said. "It’s a lot of weight to carry around. And I don’t think people focus on that when they are like, ‘That’s so cool that you do that!’”

But the job is not all bad. Seidel said he has been lucky enough to see the look on parents' faces when their kids are returned to them, and what it does for that family. He is doing some amount of good, and for that family at least, a lot of good, he said.

“There’s a balance to it,” Seidel said. “You see a lot of crap and a lot of ugliness, but you also see a lot of beauty and potentially do a lot of good. It's high risk, high reward.”

Seidel is on his sixth year of graduate school studying human osteology, bio archaeology and anthropology, but despite what he learns in the classroom, he said it is the field experience that will prepare him for a career. After seeing many cases that look the same, people start keying in on different things they don’t learn in the classroom.

“Not everybody can do it," he said. “And I was not aware if I could do it or not. I jumped into the deep end and came out OK. And since I can do it, I feel like I have a responsibility to do it.”

Glamorizing Death

Christopher Stojanowski, a professor at ASU who teaches introduction to forensic anthropology, said forensic anthropologists also work after catastrophic situations like a plane crash, train crash or a bombing.

“The goal is identification when a simpler means of identification is impossible,” he said.

He said he has a few warnings for those who wish to enter the field. First, after a decade-long career in the field there are long-term, psychologically scarring effects of dealing with those grim aspects of modern life.

Second, there is a disconnect between TV and real life, so don’t expect the reality to be like "CSI" or "Bones."

“There is no doubt that the popularity of 'CSI,' 'Bones,' or on the fantasy side of things, 'Skeleton Stories' on the Discovery Channel, has helped enrollment,” Stojanowski said.

When he taught the class in person, he had 500 students, and now that it has shifted to online enrollment it is closer to 350 students.

People who are doing forensic research can work in human rights work or military work as well, recovering G.I.’s in foreign countries or identifying individuals after war crimes or genocide, he said.

Cassandra Kuba received her doctorate from ASU in anthropology and now works teaching forensic anthropology at California University of Pennsylvania and also works as a consultant for cases on a part-time basis.

Forensic anthropologists assist investigators with the search, recovery and analysis of skeletal remains or remains that are decomposed to the point that an autopsy can't be done, she said. Then, forensic anthropologists take the remains back to the lab to determine identifying characteristics, as well as any trauma related to the death.

Kuba said certain parts of the job are harder than others.

“In the very beginning, it was difficult when looking at that decomposing mess that was once human,” she said. “Particularly children and the elderly. You get used to the smells and the feeling and the texture of death, but you don’t get used to knowing that something horrible happened to the people we are supposed to protect. It’s sometimes tough, but you learn to cope.”

Reach the reporter at akcarr@asu.edu or follow her on Twitter @allycarr2