Thanks to a program created by one of her coworkers, Terri Hedgpeth is one step closer to being able to enjoy family pictures or scenic photographs.

Hedgpeth, along with an estimated more than six million other blind adults in the U.S., could benefit from the tactile photographs created by Baoxin Li, a professor at ASU's Ira A. Fulton Schools of Engineering. The photographs, which are printed on a special paper, have raised edges that allow the blind to feel the shapes and textures pictured.

"It's been a very interesting project to see what you can represent tactilely on paper," Hedgpeth said.

The physical pictures are easy to create, taking about a minute to print, Li said. However, they must be printed using an embossing printer, making them too costly for individual members of the public.

"Hopefully we'll have advances in technology to where the printers are affordable and everyone can access these," he said.

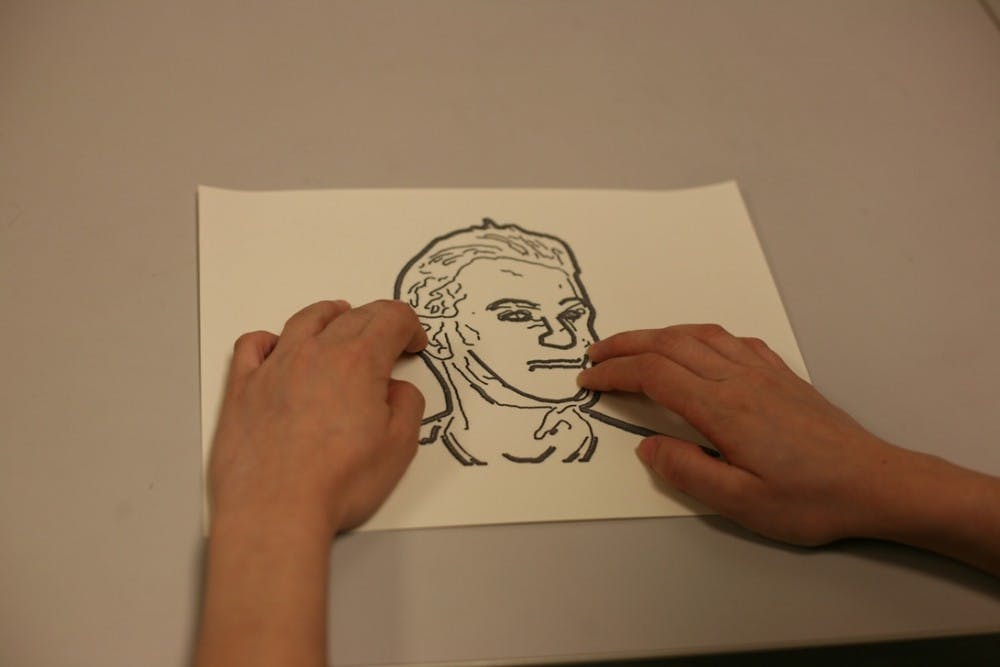

Most of the work involved in creating the pictures is done through a computer program Li's been developing for the past year and a half. The program analyzes pictures to draw out ridges, contours and other textures.

The program isolates the most prominent textures and edges for printing. The resulting tactile photograph of a face, for instance, will capture eyes, nose and mouth, but not individual wrinkles or lines.

"If you have too much information on the paper, it's going to be hard to tell what you're touching," Li said.

Because the pictures are limited in what they show, users still don't get the whole benefit of the original image, Hedgpeth said.

"You can't really pick out details of clothing," she said. "They could be wearing beautiful beadwork or a plain printed shirt and you can't tell."

The completed products look like rough sketches done with a thick black crayon or marker from a distance, but the raised edges can approximate someone's features.

However, the next step for the program is differentiating more between individual features, Li said. The computer program has a backlog of information from past pictures, allowing it to recognize shapes easily.

Now, his goal is to make it more personalized to the individual, Li said.

"We're trying to add an artistic touch," he said.

Hedgpeth, who has helped test the photos throughout development, said that just one isn't enough to fully envision the person pictured. She said a series of tactile photographs of the same person taken over time could make this more possible.

It takes training to be able to understand what the pictures show, she said. A blind user would have to have someone with fully functional sight explain what the ridges they're touching represent.

This process isn't that different from explaining traditional photographs to small children or people who haven't seen them before, she said.

"If you go to some areas of the world where people have never seen photographs and show them photographs, even ones of themselves, they won't understand it at first," she said.

Hedgpeth said she's really excited for the photos to continue developing.

"A lot of times what people forget is that there's more to life than just being able to work," she said. "Just because this is a social connection doesn't make it less important. I'd say it's just as important because human beings are social creatures."

The tactile photographs came out of the Center for Cognitive Ubiquitous Computing, an ASU research center that both Li and Hedgpeth are a part of. The center, abbreviated as CUbiC, focuses on designing devices and technology to further well-being.

Director Sethuraman Panchanathan said Li's tactile photographs are a great example of the center's efforts.

"He's doing fantastic work for our mission of accessibility," he said.

Reach the managing editor at julia.shumway@asu.edu or follow @JMShumway on Twitter.

Like The State Press on Facebook and follow @statepress on Twitter.