“The four people I was talking to were instantly dead, ripped to shreds and the other two men vaporized,” says Stanley Williams, a geology professor at ASU and lone survivor of a volcanic explosion.

It was a Thursday in January 1993 when Williams found himself in the middle of a volcanic eruption on the Galeras volcano in Pasto City, Colombia. The six people he talks about were three scientists he was working with and a local professor, the professor’s 18-year-old son and his son’s friend.

“The eruption lasted only two minutes but was throwing hot, huge, fast and sharp rocks faster than bullets,” he says, his eyes fearful. These flying, deadly stones left Williams barely alive. The scorching rocks put a hole in his skull, causing a traumatic brain injury, broke his legs, nose and jaw, fractured his spine and set him on fire. But as he says, all he could think about was the $10,000 cash he was holding for the group. So he transferred the dollars from his burning backpack to his front chest pocket.

Through all the pain and agony, Williams says he tried to remain “calm and conscious, while my friends lay dead around me.”

After a dreadful two hours, a scientist and one of his students came to his rescue. They wrapped him in a blanket and brought him down the volcano to the police station, where he was lowered onto a stretcher. He was then flown in an army helicopter to a nearby hospital where “a doctor who just moved there was able, and the only one able, to do my brain surgery,” Williams says. Although officials notified his wife, Lynda Williams, as soon as possible, she did not reach Colombia until Saturday. Williams nearly cries at the mention of Lynda thinking he was going to die before she said goodbye.

Oddly enough, Professor Williams was picked up by a United States medical jet from Miami and flown to St. Joseph's Hospital and Medical Center in downtown Phoenix. There he underwent 12 different surgeries, but the doctors predicted that, if successful, he would only know how to brush his teeth and do minor tasks.

“I only stayed in the hospital for three and a half weeks – and I can also floss my teeth,” Williams says with a smirk. In fact, after three weeks in the hospital, he had the courage to speak to the media. He had a phone interview with The New York Times and later went on “The Today Show.” But his decision had strange consequences: The day he was released from the hospital he was on the front page of The New York Times, so he snuck out the back door to hide from the “nuts” who worshiped him and the “sleazy reporters."

“The housewives of Illinois would go nuts about my story,” he says in perfect black humor. This attitude alone captures Williams’ outlook on his traumatic experience: “I didn’t die because of luck,” he says, “like someone who wins the lottery."

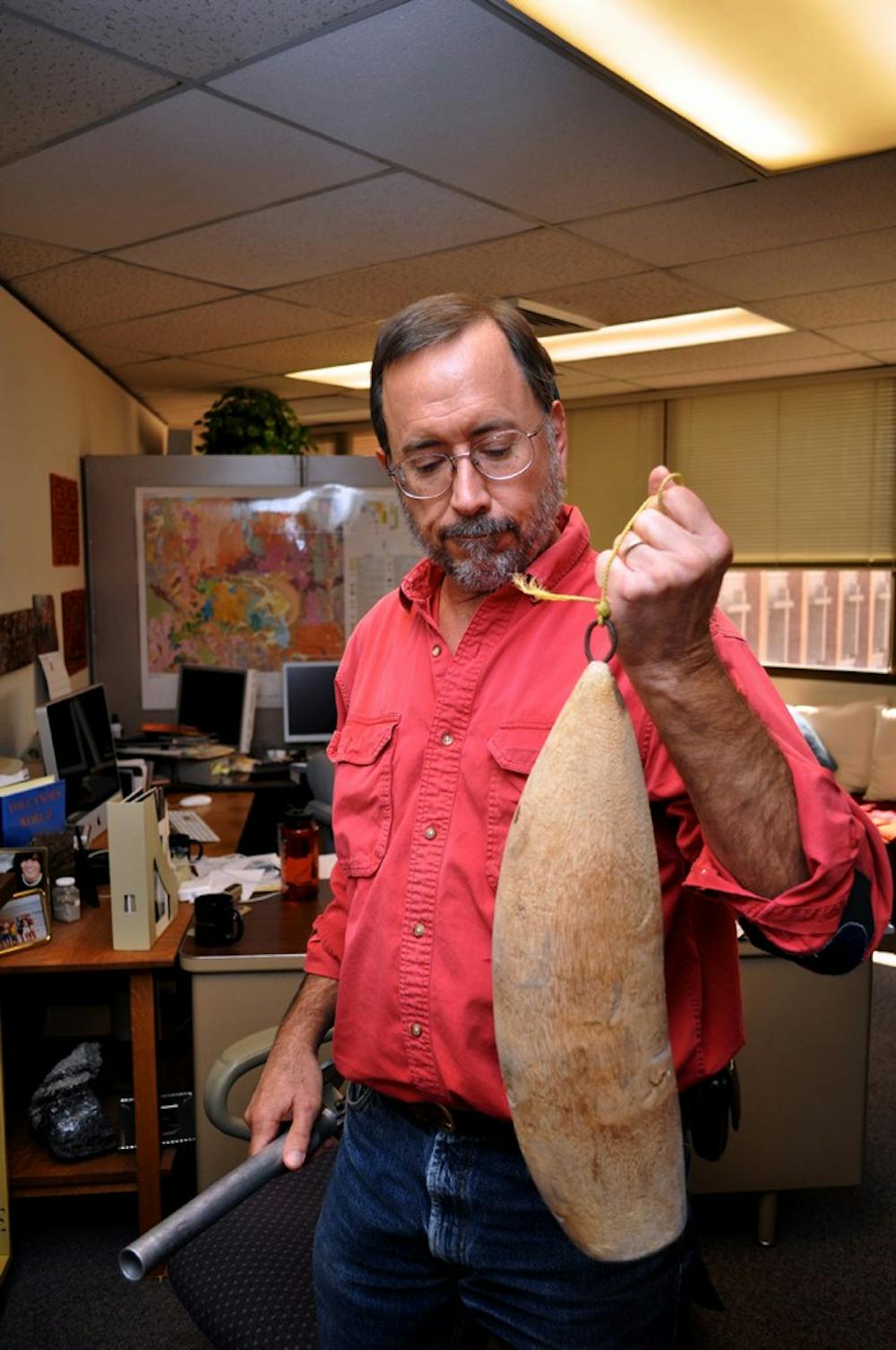

Apart from William’s horrific ordeal, he has many unordinary and outrageous stories, which include, but are not limited to: excusing himself from or dropping out of college twice, cutting his college classes to go on strike, studying for his master’s in Guatemala and his Ph.D in Nicaragua, being held at gunpoint three times (one incident with students), living in Colombia for six months with his one-year-old daughter and wife, writing a book with journalist Fen Montaigne called Surviving Galeras, publishing scientific journals in seven different languages, choosing to teach at ASU instead of the University of Geneva in Switzerland and being hired by the Unites States, international governments and the United Nations to investigate and study dangerous volcanoes and their potential damages to civilizations.

Phew.

He compares his adventures to “running around the world” – he has visited 22 countries and counting across the globe and has about a dozen stories for each one. And if he had the time he would share it all. Williams is not only an expert in his field, but also a survivor of his studies.

“Like being a doctor in an emergency room, you can’t take six months to say what’s wrong,” he says about volcanology. “You have to be confident about a quick diagnosis.”

He grew up in Jolliet, Ill., a small town outside of Chicago, and decided to become a geologist after attending a Geology 101 class, a course he ended up teaching last spring. Despite several health-related setbacks such as short-term memory loss, speech mistakes and intensified emotions, Williams remains a remarkable educator. He says he has no issue with revealing to his students his difficulties because “students are made curious,” which transforms the class into an interactive conversation, he says.

Kip Hodges, founding director of the School of Earth and Space Exploration, shares similar views on experienced teachers such as Williams.

“Most faculty do a much better job at teaching if they can weave research experience into their lectures,” he says. “In science in particular, it is important for professors to demonstrate what it means to do cutting-edge research. Stories from down in the trenches of scientific research really bring the science to life and makes for a better educational experience for students.”

Over the years, several students have had an opportunity to work alongside Williams or sit in his lectures. Brett Carr, both a former student of his and Williams’ current teacher’s assistant, sums up Williams and his experience perfectly.

“His accident in 1993 has definitely affected his teaching style. His lectures are far from what one would call typical, and he is prone to wander off topic or follow a tangent for the rest of the class period,” Carr says. “Some may consider this a bad thing, but I don't. As a student in one of his classes, you already have the textbook; you don't need that information regurgitated to you. The stories he tells when he goes off his lecture outline are usually both very entertaining and very informative. I took his volcanology class last fall, and I learned about not just what volcanology is, but what it can mean to be a volcanologist.”

Furthermore, Hodges’ personal note about Professor Williams touches home. “I think what’s so remarkable about Stan is that he was able to make a remarkable come back,” he says. “We should all be proud to have him in our community.”

Reach the reporter at ayesha.harrison@asu.edu