In the Antarctic summer, the sun disregards the cycles of night and day, making for a surreal experience. Wake up to the sun, work under the sun and sleep through its glaring rays: permanent daylight.

So what could have prompted two Arizona State University affiliates to spend their days (but never their nights) at the bottom of our planet?

Simply put: molecular cloud formation.

Christopher Groppi, a professor with a doctorate in astrophysics, and Todd Veach, an astrophysics graduate student, are team members of a research experiment aimed at learning how new stars form.

“The idea behind it is that molecular clouds rotate and condense to form star-forming regions,” Veach says.

What is unknown is how these clouds of molecular gases come to be and how long they last.

Discovering the secrets within these clouds rests on tracing carbon and nitrogen atoms to see new clouds that do not shine in any other way. These two atoms, however, emit light at a color that the Earth’s atmosphere largely blocks, and data collection must occur above or in a reduced atmospheric setting.

To achieve that goal, Groppi and Veach traipsed cross-country and cross-continent, working closely with a team of 15 others on a long-duration balloon mission. The team took to the skies in mid-January this year, the balloon’s 400-foot diameter diminished by the flat, scale-less landscape of Antarctica.

Funded by NASA in 2007, this experiment is headed by the University of Arizona, with 13 different institutions involved, including ASU, Harvard and the Jet Propulsion Laboratory. Groppi has been involved since the project’s original proposal, when he worked as a postdoctoral researcher at UA. Veach built one of the electronics modules on the telescope.

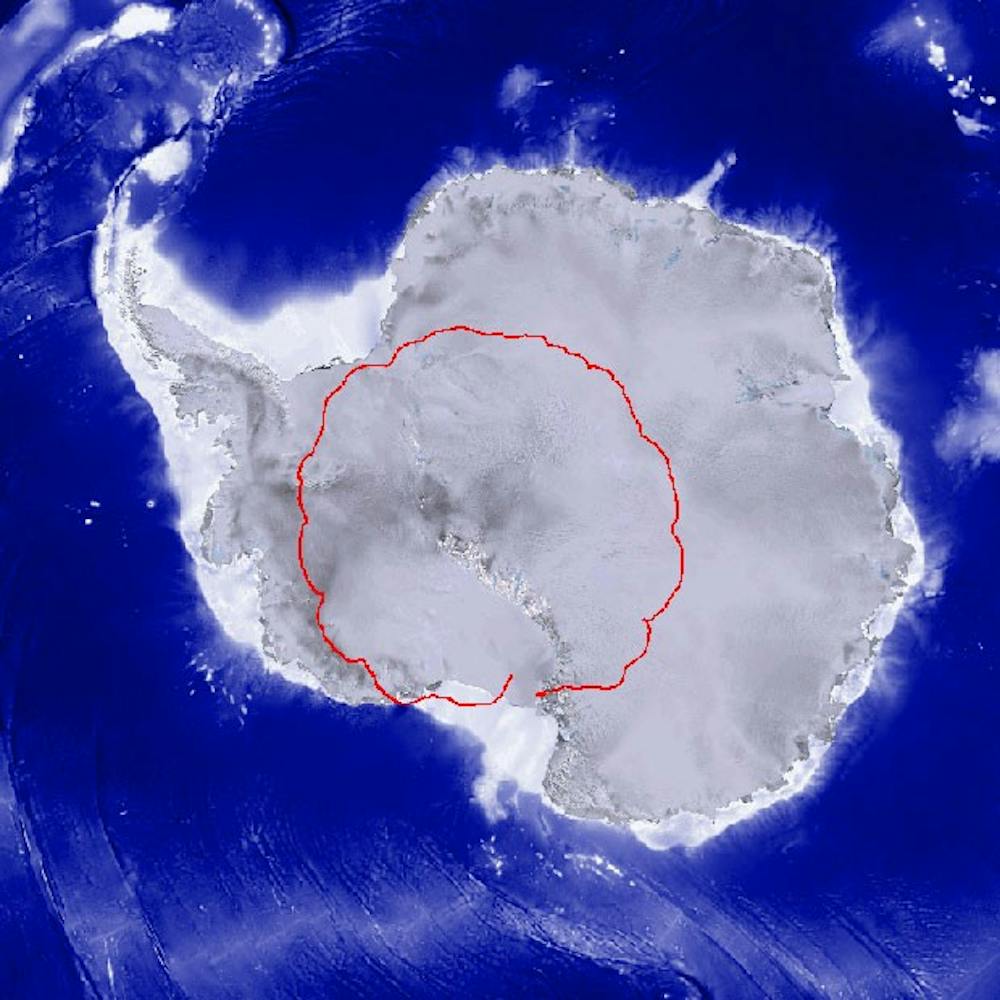

The “giant party balloon,” as Groppi describes it, which carries the telescope, is partially filled with helium, its billowing white walls expanding and solidifying as it rises. Launched from McMurdo Station on the Ross Ice Shelf, the telescope drifted 125 thousand feet above the ground, collecting data for 12 days.

The whitewashed terrain, both beautiful and alien, does not immediately welcome thoughts of scientific conquests, but Antarctica is uniquely positioned for research of this kind and has played host to more than 20 years of scientific balloon launches.

“Antarctica is the closest thing to going to space we can achieve without actually leaving Earth,” Groppi says.

Summer wind patterns below the Antarctic Circle push the balloons in a circle over the continent and allow researchers to launch and collect their instruments from roughly the same site.

Equipped with a radio detonator and a parachute for its trip down, the telescope landed on Jan. 28. The balloon was left to shred in the atmosphere.

Despite what one would typically think of the Antarctic weather, neither Groppi nor Veach found it particularly cold.

“To people from Arizona, it’s probably cold, but it was only freezing, which is an interesting statement to make,” Veach says, proudly sporting a long-duration balloon flight T-shirt.

With temperatures hovering between 15 and 35 degrees Fahrenheit, the two found the winter wear provided to them by the McMurdo Clothing Distribution Center more than sufficient. On the “wonderful days” when temperatures reached freezing, Veach says he played Frisbee outside with some of the others at the station.

Groppi, a seasoned visitor to Antarctica, marked this last trip as his fourth visit to the southernmost continent. Veach on the other hand had never been before, but said that an Antarctic trip was a goal of his since he first began studying astrophysics.

“It was awesome. It’s a surreal environment,” Veach says. “To actually experience it is mind numbing. Everyone should go.”

Contact the reporter at klhwang@asu.edu