If stereotypes have any truth to them, college students are having a lot of sex, especially at ASU. And if modern television is any indicator, every teenage girl is pregnant, or on her way there.

Despite our generation's assumed promiscuity, the facts are clear: Birth control has been widely accessible since the swinging ‘60s, but many young women still don’t know enough about it.

“By the time someone gets to college, the information they may have learned is extremely variable,” says DeShawn Taylor, medical director for Planned Parenthood Arizona. These misconceptions lead to unwanted pregnancies, she says. If a woman is wondering whether she should use birth control, Taylor has a simple answer.

“If a woman isn’t actively trying to get pregnant, she should be on birth control because otherwise she is just setting herself up for an ‘Oops,’” Taylor says.

While this fear is instilled deeply in most college-age women, the process of choosing a birth control method is not so clear. And most of it may rely on simply what a doctor chooses to recommend, Taylor says.

“Health care providers have misconceptions,” she says. “Doctors, nurse practitioners, physicians — sometimes their own personal biases influence what women choose.”

For example, many doctors recommend the tri-monthly hormone injection Depo-Provera to adolescents simply because “we don’t want teens to have to remember to take a pill every day,” Taylor says.

Meanwhile, the daily hormonal pill is the most popular, with 28 percent of women in the United States choosing it, according to a study by the Guttmacher Institute. The pill is effective but also affected by mistakes like missing a dose, says Dr. Karen Ragaini, a Phoenix gynecologist.

“Birth control pills have a great success rate with them if you take them according to their guidelines,” Ragaini says. “The true efficacy of a birth control pill, with the way [young women] take them, hits around 92 percent.”

With popular methods like condoms and withdrawal also failing about 17 percent of the time with typical use, is there any perfect method of protection?

The closest there is, Taylor says, is a LARC, or a long-acting, reversible contraceptive.

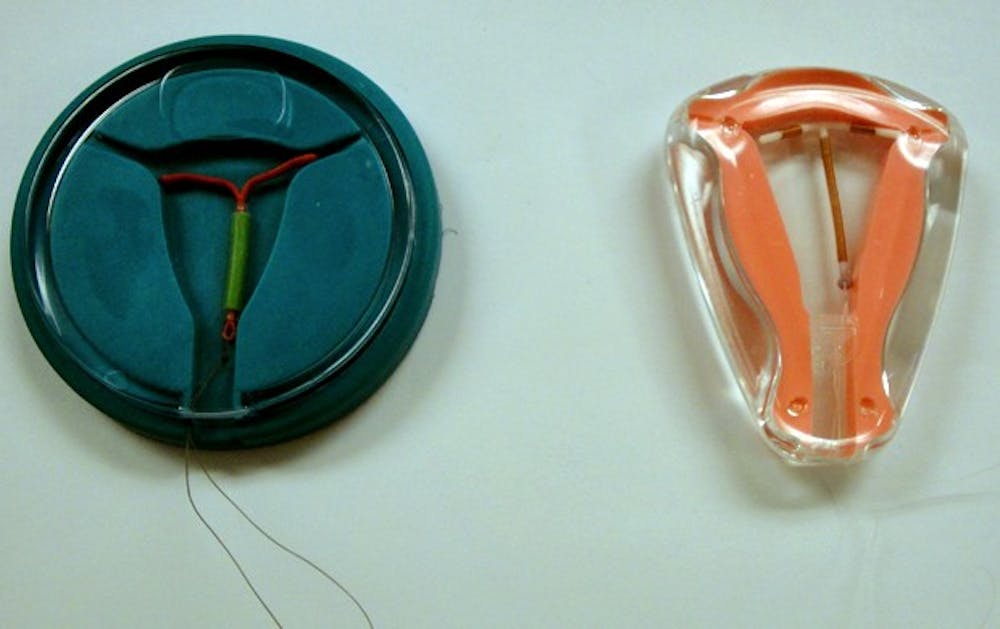

LARCs include implants — the small, plastic sticks that are implanted in the arm — and intrauterine devices, commonly known as intrauterine devices or IUDs.

Many young women don’t consider IUDs an option, Taylor says, due in part to its advertising. A commercial for the Mirena brand IUD features a mother of two who is too frazzled raising kids to remember to take the pill. Nowhere does it mention use for women of all ages, a move that Taylor finds misleading.

“Understanding that college-age women want to finish college and establish a career, the longest-effective birth control is the best way to go, which is a LARC,” Taylor says.

Despite their stellar success rate and low-maintenance status, only 5.5 percent of women in the U.S. have IUDs. Compare this to Europe, where 11 percent of women have an IUD in the United Kingdom, and 27 percent do in Norway.

What causes the cultural difference?

In the '60s, the U.S. saw an IUD called Dalkon Shield. Millions of women received it before reports came out that it caused infection, birth defects and even death. Although it was quickly recalled, that reputation lives on, Taylor says.

Modern IUDs like ParaGard and Mirena have been proven to be safe and are some of the most effective contraceptive methods available.

“It’s just as effective as getting sterilized, except when you take it out, you are fertile again within your next cycle,” Taylor says.

That success rate is leading many young women to seek information about IUDs, including Meredith Howell, an ASU junior who decided to get an IUD after nearly two years on the pill.

“I kept forgetting to take my oral birth control and I was sick of using condoms as extra protection because of it,” she says.

Beyond that, she was weary of the effects of hormones, wondering if they were causing weight gain and mood swings.

Howell received an IUD a little more than a month ago, and has loved it ever since.

“Knowing that I absolutely can’t get pregnant is awesome,” she says. “It has been really easy. My first period was a little uncomfortable, but nothing a couple ibuprofen and deep breathing couldn’t fix.”

The process of getting an IUD was simpler than Howell expected; after an initial consultation, she called the doctor’s office the day she got her period and had an appointment for the next day, where she likened the procedure to a typical pap smear.

Dr. Ragaini says the procedure is the same in her office.

“The whole start-to-finish is not very long, maybe five minutes,” Ragaini says.

One of the only reasons she doesn’t typically recommend it to young women is because IUDs provide no protection from STDs, which may be why so few women are told about them.

Reach the reporter at kaila.white@asu.edu