Traffic, congestion and related pollution in large cities could be problems of the past with the implementation of a futuristic, personal rapid transit system called SkyTran, according to the system’s designers.

Unimodal Inc., the project’s overarching company, originally looked at ASU’s Polytechnic campus as a possible site for the first track, said Jon Fink, director of ASU’s Global Institute of Sustainability.

The plan fell through because the details weren’t sorted out fast enough to meet the pending deadline for a federal grant Unimodal intended to apply for.

“This summer, when stimulus fund grants became available from the U.S. Department of Transportation, Unimodal suggested that we jointly apply for one,” Fink said. “During our discussions, the focus shifted to the ASU Tempe campus, although in the end there wasn’t enough time to get organized before the deadline.”

Still, if Unimodal receives the federal grant money it applied for last month, construction of the first public line will begin in St. Tammany Parish La., and be completed by 2012.

Once that line is operational, Unimodal has its sights on Arizona and California as its next destinations because of the environmentally friendly power options their climates provide.

“Arizona and California are the perfect places to use solar and wind power, which is something we are interested in,” Unimodal’s Arizona representative Jerry Spellman said. “That is where we will likely go next.”

Behind the concept

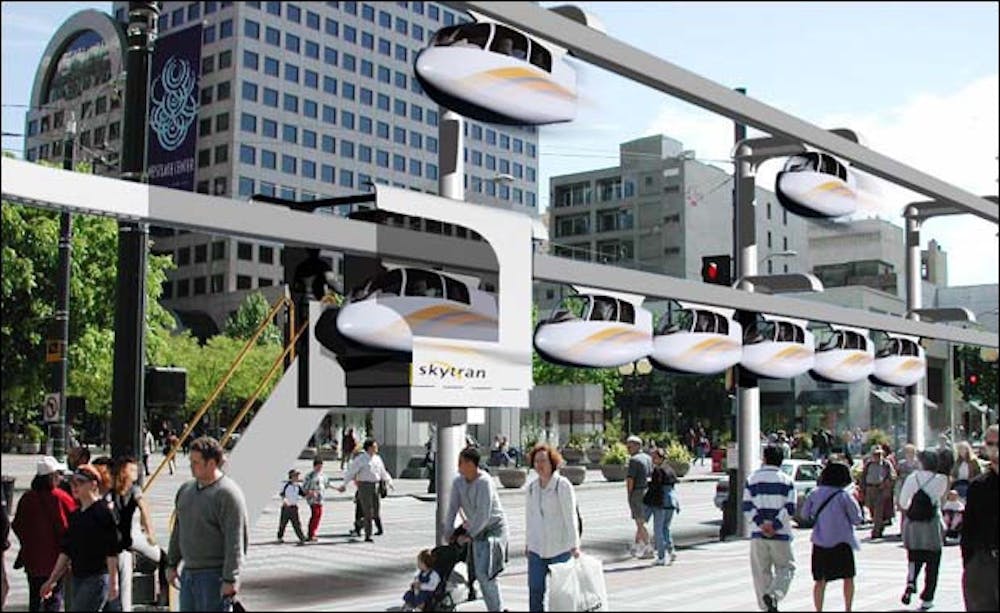

The design for the automated system consists of small individual vehicles that operate using magnetic levitation — maglev — and take one or two passengers directly to the destination of their choice, Spellman said.

“SkyTran doesn’t stop except where your destination is, so passengers are carried at high speeds directly to the place they designate,” he said. “For example, if you board at ASU and want to go to Gilbert, you don’t have to go through Mesa first or stop every half-mile along the way.”

Stations, referred to as portals, will be placed every quarter- to half-mile, depending on the traffic density of the area.

The track, called a guideway, will be elevated above roads and pedestrian areas by support poles and can run in one or two directions.

The SkyTran track is thin enough to run above a bike lane, which Spellman said will allow it to operate almost anywhere.

“The seats are tandem seating, so it’s a very narrow vehicle that can operate in small areas like ASU’s malls, for example. It can be put pretty much anywhere,” he said. “It can be attached to buildings and even go inside buildings eventually, like into an airport terminal or hospital emergency room.”

Vehicles move along the guideways at speeds up to 150 mph, and average 70 mph within cities, Spellman said.

In order to stop and allow passengers to disembark, vehicles pull off the main guideway into portals so they don’t slow down traffic.

“It works kind of like an on-and-off ramp of a highway, but it’s automated so it doesn’t slow other vehicles down at all,” he said.

Students react

Direct routes combined with high speeds appeal to many ASU students, like microbiology sophomore Brian Klein, who said he currently finds these qualities lacking in Tempe’s transit system.

“The light rail isn’t really near my house, so accessibility [is an issue],” he said. “Plus I don’t really go to downtown Phoenix that much.”

He said he would use SkyTran based on the benefits of accessibility and speed alone.

“Since SkyTran would be able to pick me up essentially from my house and it doesn’t have any designated stops, I’d get to go where I want to go quickly,” Klein said.

Not all Tempe residents agree the city needs such an elaborate, futuristic system, however.

Sustainability junior Jared Regan, who takes the light rail to class daily, said he thinks the light rail is sufficient for the Valley.

“I love riding [the light rail]. I think it’s a great system and it’s never made me late,” he said. “I think simple systems like the light rail functioning around existing and developed transportation hubs work [for Tempe]. It’s reasonably energy efficient and with the subsidized fare it promotes public transportation well.”

A safer alternative

SkyTran officials say the system has many benefits beside speed and direct routes that other mass transit systems don’t.

The cars drive and park themselves, so passengers don’t have to worry about being distracted, which poses a serious safety hazard on roads, according to the U.S. Department of Transportation.

The use of maglev also increases safety by eliminating all moving parts.

With no wheels or parts of the track being subjected to regular wear-and-tear damage, the risk of breakdowns and crashes due to mechanical failure is almost nonexistent, Spellman said.

Not having to repair such damages also helps cut costs.

Maglev also makes derailing impossible, increasing safety even further, Spellman said.

“The magnetic force lifts the vehicles so they are virtually floating through the guideway, and the energy to do that can come from almost any source,” Spellman said. “The vehicles are so lightweight that solar power would be enough. You couldn’t run a light rail on just solar [energy].”

Other advantages include being environmentally friendly, high capacity and inexpensive to construct compared to other mass transit systems, he said.

The support poles are also able to incorporate telecommunication and fiber optics, enabling cable and Wi-Fi in the cars.

Building the SkyTran

Spellman said this design simplifies construction compared to other systems like light rails and streetcars by incorporating all parts of the system into one above-ground line.

“It doesn’t require tearing up streets or other heavy construction work,” he said. “All that goes up are the poles that support the guideway, so it never comes in contact with intersections or traffic at all.”

Some students who now utilize the light rail on a daily basis remember the hassle of construction.

“I remember [construction] took years and killed all the businesses along the light rail,” Regan said. “A lot of old businesses went under, and it was a real shame.”

Metro Light Rail spokeswoman Hillary Foose, however, said light rail construction didn’t hurt businesses along the track.

“In May 2000, before we even started construction, and also during construction, we saw a large amount of investment by both public and private investors along the track,” she said. “Since then, there’s been $7 billion in investments. That’s from a mixture of things, including ASU’s Downtown campus, residential complexes, mixed-use buildings and more.”

Foose said this is an unusual trend for new mass transit lines.

“We saw [the investments] before the light rail opened, which is kind of unusual because people typically wait to see what the ridership is first,” she said. “I think this is in part because public transit is becoming a national issue and more and more people are starting to [utilize] it.”

Funding the project

As far as funding for the light rail itself, about half the money came from federal grants and the rest from sales taxes throughout the Valley.

This is one other argument Unimodal has for its system over other mass transit systems: SkyTran costs $10 million to $15 million per mile to build, compared to about $70 million per mile for the light rail. As a result, SkyTran could be fully funded by government grants and private investors, Spellman said.

In September, Unimodal applied to receive the federal Transportation Investment Generating Economic Recovery grant to build the first functional public system.

Currently, the only line is a short test track at NASA’s Ames Research Center in Mountain View, Calif.

Unimodal applied for the grant with several partners in St. Tammany Parish, La. which is where the first fully.

According to information distributed by the U.S. Department of Transportation, the grant is part of the federal stimulus money, the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009 and is designed to provide funds for transportation-related capital investments that significantly impact the city where they are built.

Up to $1.5 billion have been allotted to the program and will be distributed among the applicants as the Secretary of Transportation sees fit.

Unimodal has requested $75 million to build the demo track.

If Unimodal receives the grant, which will be announced in February 2010, Spellman said it would be enough funding to have the Louisiana system up and running by February 2012.

“We think this is our strongest proposal yet, and we have a lot of good partners in Louisiana including NASA, so hopefully it will work out,” Spellman said.

If this happens as planned, additional grant money from both federal and local governments interested in implementing SkyTran in their cities should be accessible once the demo is up and running, Spellman said.

The company also plans to recruit private investors.

After the Louisiana experiment, Unimodal intends to construct SkyTran in several other cities, including Phoenix and Los Angeles as soon as enough funding is acquired.

Spellman said it is unclear when this will be, however.

Once it’s built, the costs to keep SkyTran running should be low enough to be paid for through fares.

“SkyTran doesn’t have to be subsidized by taxpayers because it’s an automated system,” Spellman said. “It’s operated by autonomous computers in each car so it doesn’t have labor costs like other systems.”

This would allow the system to run 24 hours a day without increasing costs.

Spellman also mentioned potential for sending small freight on the same passenger lines, which would increase income and help offset operation expenses.

Looking forward

Unimodal is not the only company working on such advanced personal rapid transit systems.

Companies in the U.S. and Europe are working to develop similar systems as well as automated systems that use existing cars and roads.

ASU faculty is also beginning to investigate possibilities for personal rapid transit around campus and the greater Phoenix area, Fink said.

“ASU has lots of relevant expertise among our transportation faculty, computer scientists, geographers, mechanical engineers and architects,” he said. “I’ve begun organizing this group into a team that can take a systems approach to evaluating the future of [personal rapid transit] for ASU, Arizona and beyond.”

Fink also said he is optimistic about the future of such systems.

“I think that Personal Rapid Transit systems like Skytran represent an important component of future sustainability solutions. They are relatively inexpensive and very energy efficient,” he said. “Overall, I’m quite enthusiastic about PRT systems.”

Reach the reporter at keshoult@asu.edu.