ASU researchers may have found solutions to reduce the booming, multi-billion-dollar costs of hip and knee replacements in the U.S.

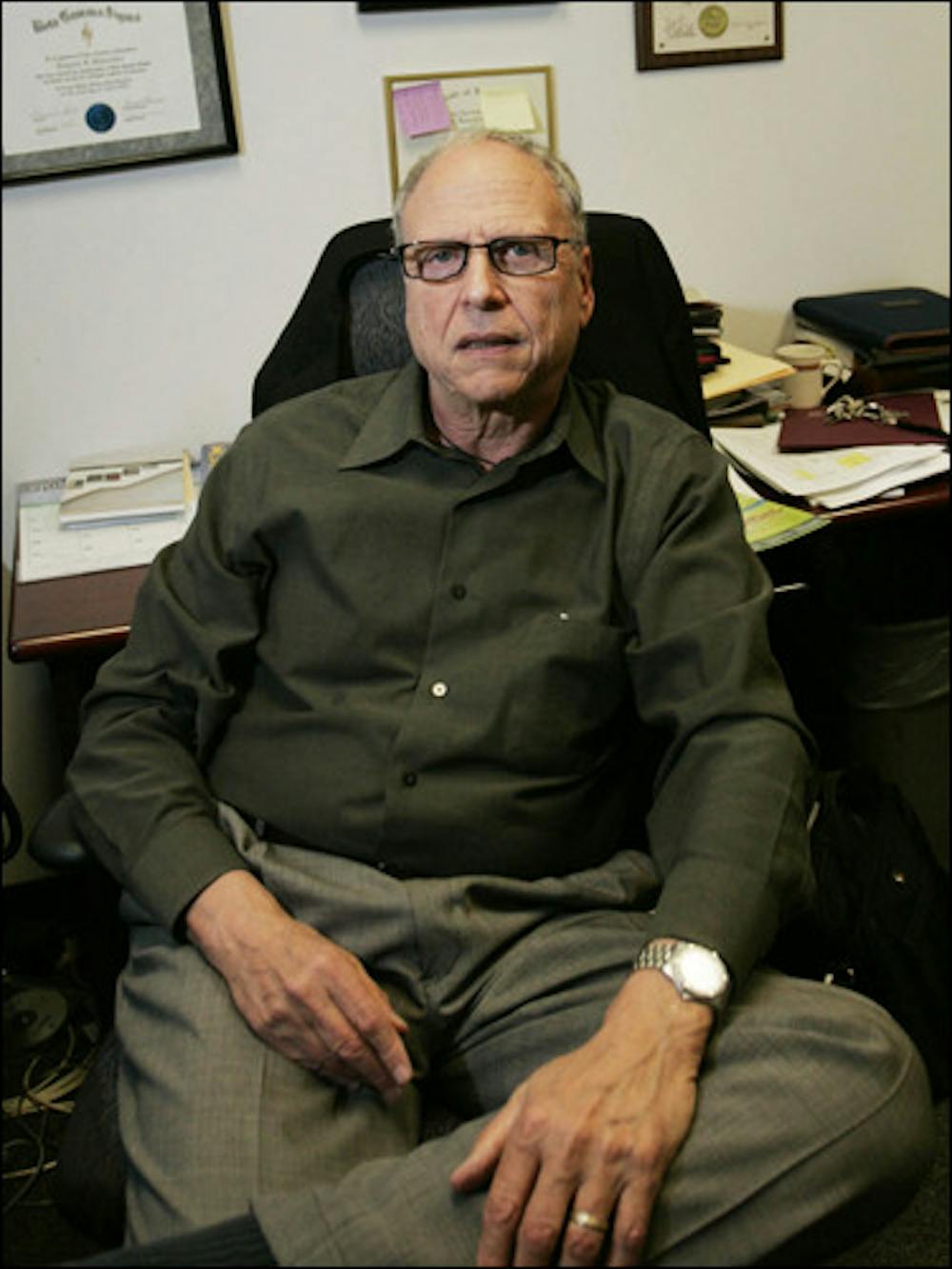

Increasing transparency and available information about hip and knee replacements around the country would increase efficiency and reduce medical expenses, said professor Eugene Schneller of the School of Health Management and Policy at the W. P. Carey School of Business.

In 2004, hip and knee replacements cost U.S. hospitals about $11 billion, Schneller said.

“As the baby boomers get older, they’re interested in having those surgeries,” he said. “And the cost of those is tremendously expensive and growing.”

In 2030, the costs to Medicare for hip and knee replacements in the U.S. could be $50 billion, he said.

“Hospitals have a very difficult time controlling costs,” he said.

Schneller is director of the Health Care Supply Chain Research Consortium — a collaborative research effort between the School of Health Management and Policy, the Carey school and industry partners like hospitals and distributors.

He has been working with ASU research associate Natalia Wilson for several years to find strategies for reducing medicals costs while increasing the efficiency of medical treatment.

Schneller and Wilson, along two professors from universities in California, published a research paper about their research into controlling the costs of hip and knee replacements in the November/December edition of Health Affairs.

Schneller said costs of hip and knee replacements in the U.S. are rapidly increasing, but little research outside of ASU has been done in the area to increase efficiency.

One problem contributing to mounting costs, Wilson said, is that many hospitals sign non-disclosure agreements that prevent the institutions from releasing how much money is spent on hip and knee implants. Some hospitals might pay twice as much for a knee replacement as others, she said.

“It makes it very difficult for hospitals to understand what they’re paying,” Wilson said. “The biggest drawback is that a hospital may be paying an inflated price for a product.”

A solution to this is to create national registries that would track hip and knee replacement surgeries and keep-updated information on implant prices across the country, Wilson said. Countries like Sweden already have such registries in place, she said.

Conflicts of interests can pose a threat to the efficiency of hip and knee replacements nationwide, such as the necessary relationship between a doctor and a supplier, Schneller said.

Although a representative from an implant company can offer valuable advice and coaching during a surgical procedure, as well as benefiting patient’s care, there are drawbacks, he said.

“One of the concerns is you don’t want the supplier in there constantly selling the most expensive implant,” Schneller said said. “In a sense, that’s sort of been the elephant in the room.”

And doctors who stand to benefit financially from certain procedures may not choose the most effective type of treatment, he said.

“If the physician has a huge economic stake … studies have shown that starts to influence judgment,” he said. “You want the best implant at the best price for the best outcome.”

Wilson said the ideal relationship between a doctor and a supplier is one that emphasizes clinical evidence for treatments, rather than the costs associated. And doctors need to be more open about their relationships with suppliers, she said.

“There’s need for greater transparency of that relationship,” she said.

Reach the reporter at matt.culbertson@asu.edu .