When video game Halo 2 came out, 23-year-old Mike Charles waited in line for seven hours to get a copy and then played for 14 straight hours when he got home.

Their love and dedication to gaming aside, the closest that Charles and other gamers can come to feeling as though they are actually in the game are vibrating controllers that weakly shake when something happens. One ASU researcher said that could someday change.

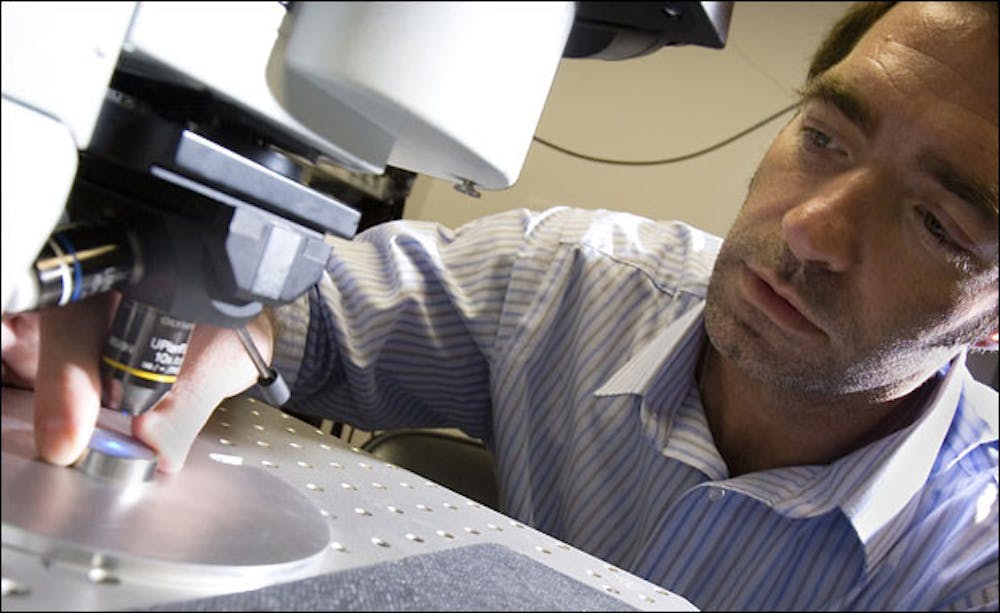

Jamie Tyler, an assistant professor in the School of Life Sciences, is looking at theoretical ways to stimulate neurons in the brain to send specific signals throughout the body that could create an actual virtual reality.

Tyler has focused on neuromodulation, the use of low-frequency ultrasound waves to target groups of neurons that control different feelings or sensations throughout the body.

“We can make the body experience things by stimulating certain parts of the brain. It’s almost like the movie ‘The Matrix,’” Tyler said. “Imagine taking a vacation without even going anywhere.”

Though the research sounds more like science fiction, the project can be applied to more serious areas than battling robots or scoring touchdowns.

Using ultrasounds to stimulate neurons in the brain can theoretically impact diseases like post-traumatic stress disorder and Parkinson’s disease, Tyler said.

“We are focusing mostly on the medical implications of neuromodulation,” Tyler said. “Anything that involves neurological injury to the brain could potentially be healed by neuromodulation.”

Sony has already patented similar technology in what they call the Ultrasound Brain Beam Matrix with the hopes that someday they could use the idea for video-game technology.

Elizabeth Boukis, spokeswoman for Sony Electronics, told New Scientist magazine in 2005 that the patent was mostly speculative.

“There were not any experiments done,” she said. “This particular patent was a prophetic invention. It was based on an inspiration that this may someday be the direction that technology will take us.”

Tyler said that the next step in the research is to study how to better focus the technology to get to specific proteins in the brain.

He said that unlike high-intensity ultrasounds that are used to kill things like cancer cells, low-intensity ultrasounds don’t damage the tissue.

“There is no way for us to get to a specific cell,” Tyler said. “The thing about ultrasounds is that they can get through the skull and can reach specific groups of cells, but at a low frequency they don’t damage the tissue.”

Reach the reporter at jaking5@asu.edu.