Two anthropologists have identified a way to bridge the gap between science and religion.

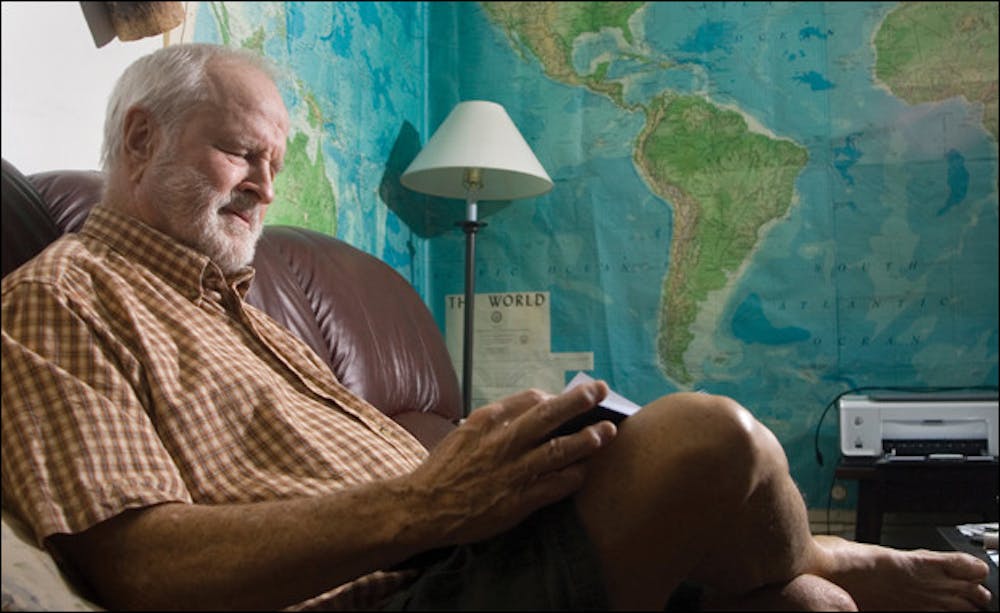

Lyle Steadman, an emeritus professor at ASU, and his former graduate student Craig Palmer developed a new method to scientifically study religious behaviors through verbal communication — a project they’ve been working on for almost two decades.

The professors recently published their research in the book, “The Supernatural and Natural Selection: The Evolution of Religion.”

Steadman said the goal of their book is to examine how religion has come to be universally practiced in all societies.

“We are trying to explain how religion came to be universal and how religion has helped religious individuals leave more descendants than non-religious people,” said Steadman, an emeritus professor of human evolution and social change.

The professors concluded religious behavior can be identified as an individual communicating his or her acceptance of a supernatural claim.

The act of acknowledging a religion is religious, although the person is not religious himself or herself, he said.

“Our approach allows the question of why religion exists, and why religious behavior is found in every culture, to begin to be answered scientifically for the first time,” said Palmer, now an associate professor of anthropology at the University of Missouri-Columbia’s College of Arts and Science.

In their research, the professors discovered religious behavior encourages family-like behavior amongst individuals who are not biologically related.

“Religious behavior everywhere promotes behavior between individuals normally found only between families,” Steadman said. “This is why religion everywhere, tribal and modern, uses a kinship idiom to promote behavior.”

For example, Christians refer to God as the Father and the Virgin Mary as Mother Mary.

The professors’ method is important because it allows scientists to apply Darwinism to the study of religious behavior, Steadman said. This approach can be used to determine how religious behavior led individuals to leave descendants.

“Hopefully, [this study] will make social science more empirical and hence subject to disproof,” Steadman said. “Hopefully also, social scientists will see that Darwinian selection applies to traditions as well as to genes.”

Palmer and Steadman both said they hope professors and anthropologists will integrate the book into the classroom.

“Our book is designed to be used in university-level courses on anthropology and religion, as well as read by the general public, so we hope it is useful to teachers interested in explaining religious behavior scientifically,” Palmer said.

Both professors said they recognize their book may incite backlash.

“People will be offended because we’re challenging virtually all explanations of religion,” Steadman said. “They all assume religious belief causes religious behavior, and yet they cannot demonstrate that it’s true.”

Reach the reporter at lauren.gambino@asu.edu.