Marisa Johnson graduated from ASU in 2002. Two years later, she thought she'd be dead.

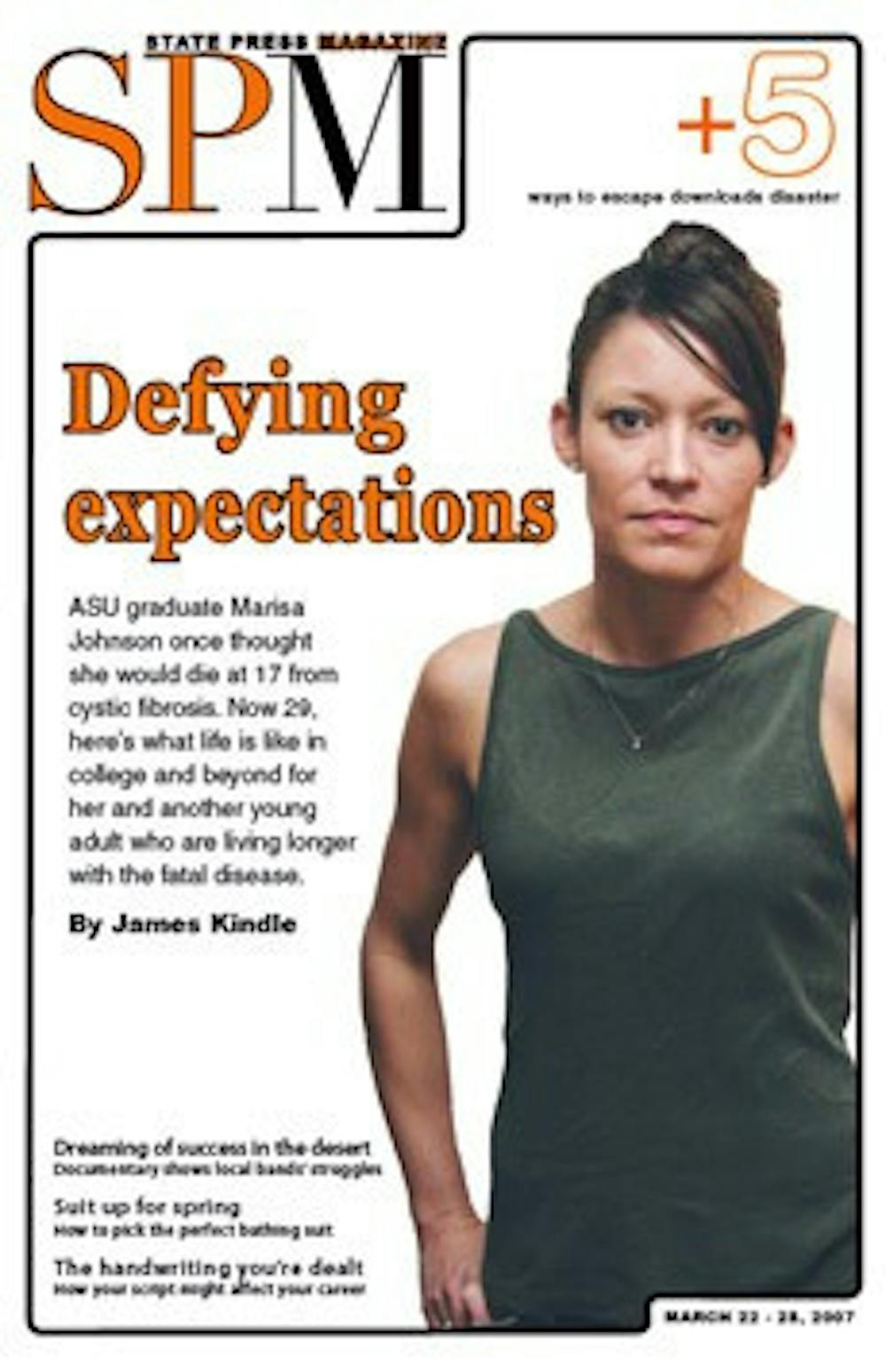

Johnson, 29, appears as healthy as her peers. Only her lean frame and an occasional hacking cough reveal that Johnson might not be in perfect health.

But Johnson is actually very sick. She is one of about 30,000 Americans living with cystic fibrosis, a genetic disease that causes lung and digestive problems and often early death.

"When I was 11, I saw an article that said the average life expectancy for someone with CF was 17," Johnson says. "I never thought I'd be 29 years old."

But as more treatments and medications become available and parents are educated earlier in properly treating children, CF patients' life expectancy has jumped to 36.5 years, according to the Cystic Fibrosis Foundation.

As life expectancies have increased, so too have the number of CF patients attending and graduating from college.

Johnson and others like her, including UA student Ronnie Sharpe, are a new generation of students attending universities while simultaneously battling a killer disease.

'Everything ... comes back to CF'

"I think absolutely everything that I do and think about always comes back to CF," Johnson says. "Everything. Everything."

This all-encompassing nature of the disease, which varies in severity from person to person, had a large impact on Johnson's time in college as well. She says as she neared the end of high school, she wanted to attend ASU.

"I kind of felt like if I didn't do it, I was giving up already," she says. "I wanted to be like everybody else, to take the track."

Johnson received a bachelor's of interdisciplinary studies in communications and family studies; she now works as a nanny because the job allows her flexibility when she needs medical treatments. Her five years at ASU were fraught with bouts of illness leading to two missed semesters. During college, Johnson also lost her younger sister, Wellesley, to the disease, when she died in 2001 at the age of 18 from complications following a lung transplant.

"I've seen a lot of friends die, especially my sister, and seen other kids her age pass away. It kind of gives you a different perspective on life," Johnson says.

When scheduling college classes, the disease limited the type of classes Johnson could take.

"I would take athletic classes at ASU, but I had to drop, because I would cough up blood," Johnson says. She has since had three operations on her lungs to stop the bleeding.

Another of Johnson's biggest obstacles in attending ASU was overcoming the fear of being rejected for her disease.

"Mainly for me, I'm just very sensitive," Johnson says. "I was afraid I wouldn't make friends because they'd think I was this sick girl."

Johnson says she even avoided getting pulmonary treatments at her apartment at Apache Commons because she worried the claps of respiratory therapy, in which a nurse pounds on her back and chest, would attract neighbors attention. Instead, she would go to Campus Health Services between classes for treatments.

Johnson says she always thought people were snickering when she coughed, so if she started coughing, she tried to coax friends to cough too.

This insecurity extends to difficulties with relationships, Johnson says. Johnson's body bears markings of her treatments, including a scar across her stomach from a CF-related surgery as an infant and a nickel-sized device for IVs that protrudes from her back. At first, Johnson is timid about discussing her disease with dates.

"I'd hold off on telling people," Johnson says, saying she'd tell people her cough was "just like asthma."

Though her experiences with male reactions have generally been positive, Johnson says she's had some negative responses. She also broke off a one-year engagement last year because she does not feel right having children.

"I could [physically] have children, but how long would I be there for them?" Johnson says. "I would want to [have a daughter and] name her Wellesley. I would love to be a mom, [but] it is what it is. ... I can't imagine someone who'd really want to be with someone who deals with these things, and it stinks."

Despite these hardships, Johnson maintains a positive outlook on life.

"I'm not thinking, 'Woe is me,'" Johnson says. "I know I'm blessed and even my sister, I know she's blessed. I have it so much better than many other people."

'Me against the illness'

UA graduate Ronnie Sharpe, 27, also says he sees his life with CF as more of a blessing.

"I've met so many people as a result," Sharpe says. "I appreciate my family and my life more. It has shaped the way I live and look at my life."

Sharpe also experienced the challenges CF can present in balancing time in the college classroom and time in the hospital. Sharpe graduated in 2004 with a bachelor's in psychology.

"One semester, I was hospitalized, gone two to three weeks," Sharpe says. "When I came back, four of [my] five teachers said I'd missed too much time, and they withdrew me from the class."

Sharpe spends about 75 to 80 days each year in the hospital for regular visits informally called "tune-ups." During their stays, CF patients go through respiratory therapy sessions, aerosol treatments to make breathing easier and feed the body antibiotics, sessions hooked up to an IV, and weight-gain treatments.

After his negative UA experience, Sharpe jumped around at various institutions before returning to graduate at UA after six years in school.

Sharpe says he rarely thinks about having CF when he's not sick - until recently, his lung function was as good or better than his peers - and always knew he would get a college education.

"My mom would never let me use CF as an excuse to get out of anything," he says. "She would push me to do sports, to do volunteering. I never doubted I could go to college."

Sharpe now owns and works at different charitable clothing companies and says the disease doesn't interfere with the goals he has for his life. He wants to continue to volunteer and get married and have kids.

"Just because doctors say 'Your life expectancy is this,' or 'You probably shouldn't expect to go to college' ... that fuels me," he says. "I see everything as a competition. I want to do my best at life."

This approach characterizes Sharpe's fight against the disease as well.

"That's kind of how I treat the disease; it's kind of me against the illness," he says. "I don't know what winning looks like, but I'll win."

'Adding tomorrows every day'

Both Johnson and Sharpe thank ever-evolving medical treatments that help them to go to school.

"I'm here, and I've seen the benefits of the new medications," Johnson says. "I know I wouldn't be able to graduate college or work 40-hour jobs if I didn't have those new [treatments]."

These new treatments are the objective of the fundraising organization the Cystic Fibrosis Foundation, says Jan Lee Sproat, executive director of Arizona's chapter.

"Our goal is, of course, the cure, and keeping those with cystic fibrosis more healthy, so that when that cure comes they are more able to readily accept it," she says.

The group operates under the mission "Adding tomorrows every day." With new treatments, the average life expectancy has jumped four and a half years since 2000, Sproat says.

"Care centers used to be just for children," she says, "Now they've developed programs for young adults, [such as helping them in] choosing college and so forth."

Suzanne Hermine, a counselor at the Cystic Fibrosis Center at Phoenix Children's Hospital, provides college guidance for some of the over 200 patients who use the center. CF can exacerbate some of the problems all students face when leaving for college, especially separation from parents, Hermine says.

"Our patients are growing up with their parents so involved," she says. "When they transition and go to school ... they're launched on their own, and I think it's very challenging because the parents aren't around."

Hermine also cites handling the stress of college and balancing health with wanting to party and have fun as other difficulties faced by CF patients.

Of the college-age students she helps, Hermine says only a small number grew up with parents that didn't think they would make it to adulthood or have a chance to attend college.

"A lot of our patients are highly motivated, and they want to accomplish as much as they can in life," she says.

In 2005, 57 percent of CF patients had attended or graduated from college, according to the CFF's most recent figures.

Though her longer life has been a blessing, Johnson says it's difficult to adjust her expectation that she would have an earlier death.

"What happens when you live past that age you were supposed to live to? What do you strive for?" Johnson says. "[With new medications], I could be 50. What am I going to do, be a nanny for the rest of my life?"

Johnson also says her relatively good outward health might send the wrong impression about the seriousness of the disease.

"People might pooh-pooh it as not as devastating as it is," she says. "I'm blessed that I have a normal life but know that it is a struggle."

Xa Johnson, Marisa Johnson's father, said that his daughter's good health has allowed the family to be "a little more complacent" in not worrying about the disease, but this is becoming harder as Marisa's health worsens. Marisa Johnson says she's lost about 15 percent of her lung function in the past two years.

"She's at the point in her life where one severe illness - one bout of the flu - could put her at transplant time, and transplant time isn't easy," Xa Johnson says.

Marisa Johnson says she doesn't want to get a lung transplant.

"I know close friends, two people, who've passed away within two years [of getting transplants]," she says.

'A way to leave this world'

Both Johnson and Sharpe say they've relied on their Christian faith to get through the trials of the disease.

"Going through what I'm going through, I want to believe I'm going somewhere, that I'm going to see my sister again, that I'm going to see my family again," Johnson says. "I may be leaving early, but I'm going somewhere. If I didn't have that, things would be a lot more difficult."

Sharpe, whose CF is classified as moderate, says he doesn't spend much time thinking about dying from the disease.

"I look at my life like a car lease," he said. "God gave me my life, and it's on a lease, and I'm going to go over on the miles."

Johnson, whose CF is classified as severe, says she has times where she is afraid.

"If I could choose a way to leave this world, I would leave the way [Wellesley] did," she said. With her family there, Johnson's sister was able to say goodbye before she died, and she received medication to ease the pain. "I'm scared how it's going to happen - that it's not going to happen like Wellesley," Johnson says, her brown eyes briefly gazing away.

Johnson says she worries about little things, like that her apartment won't be clean when she dies. She also manages to joke about what her funeral will be like.

"I keep telling my parents I want them to play 'Another One Bites the Dust' at my funeral," she says. "My parents would never do it, but I think it would be hilarious."

More than being afraid, Johnson says she's impatient.

"I just want something to happen," she says. "God give me a sign. Let me know that I'm going to live for more than five or 10 years, or let me know that I'm going to get the flu soon."

Dealing with a reduced life expectancy is one issue that many CF patients handle at a young age, but many accept it and go forward, Hermine says.

"[CF patients] are kind of forced to face issues that you and I might not face ... in the teen years," she said.

For now, Johnson's goals involve living in the moment.

"I want to spend time with my family," she says. "If I get the opportunity to travel, I take it. I'm not about stacking up all my savings because what am I saving it for? I could get the flu tomorrow, and this could all be over. Life's too short to take for granted, you know?"

Reach the reporter at james.kindle@asu.edu