On the first Friday of every month, humble brick buildings turn into houses for festivals of light and sound. Innocent front yards are transformed into outdoor clubs as DJs spin records while pedestrians venture off the sidewalk to try a few new dance moves. The walkways come alive with people from every side of the Valley: roller derby enthusiasts, punks, soccer moms and college students. Appropriately titled "First Fridays" what started as an agreement between a few galleries to hold openings on the same night has turned into one of the largest art walks in the country.

A perusal of newspapers across the country reveals such art walks aren't uncommon in major cities and neither are the problems that come with their success. The problems are generally associated with the term gentrification. The Merriam-Webster Dictionary simply states that gentrification is "the process of renewal and rebuilding accompanying the influx of middle-class or affluent people into deteriorating areas that often displaces earlier, usually poorer, residents." This often means a group of artists uses low-rent, poor areas of town to set up shop. As their patrons begin to make frequent visits, new businesses spring up, richer people move in, and people who have rented there for years are forced to move out. Here SPM talks to gallery owners and city officials in Phoenix to reveal how complex the problem of gentrification has become.

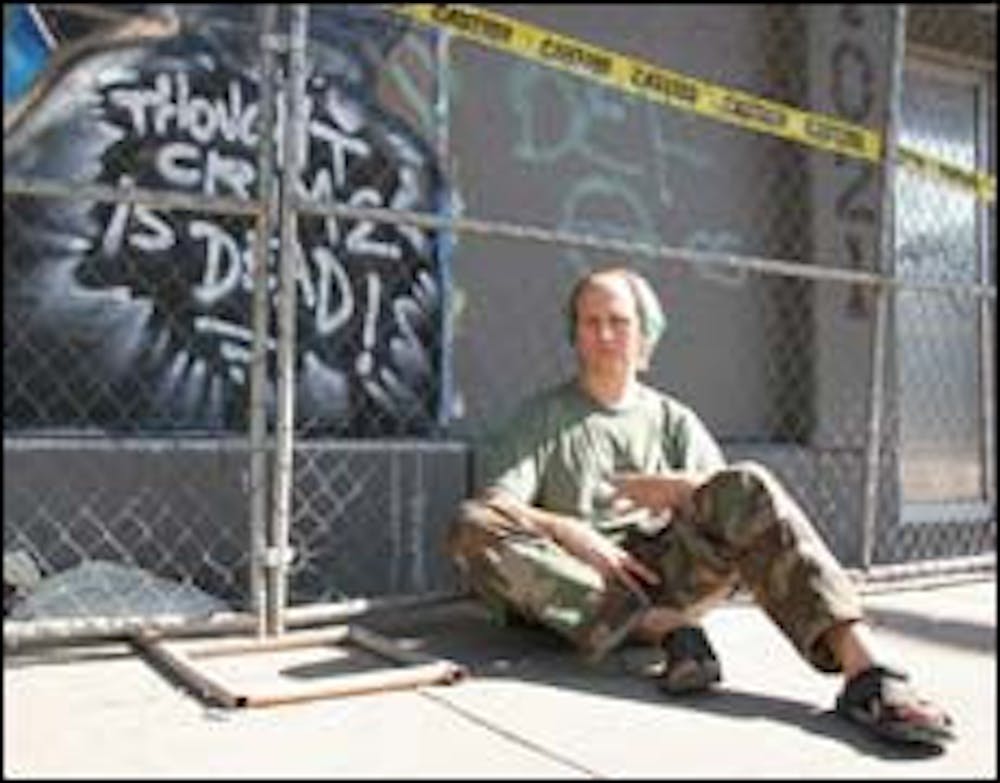

Thought Crime

Michael 23 moved to Arizona from Illinois in 1987 to pursue an engineering degree at ASU. Eighteen years later, he is the primary organizer behind First Fridays and the founder of Thought Crime, an active artists' collective. It started in 1989 when he began volunteering for a few galleries before starting the Thought Crime collective.

"In engineering, they train you to solve problems," he says. "In Phoenix, it became apparent that I could participate in something that was bettering the world around me -- I saw a direct way to help resurrect a society."

A five year stint in Tempe ended because 23 says the city was "fairly repressive for collectives." He says the city enforced archaic laws preventing three unrelated adults from living together, and police didn't take kindly to Thought Crime's public art events, either. He says they frequently came to break events up, and went so far as to tell Thought Crime's landlord that the artists were practicing satanic rituals. In 1995, Thought Crime moved into a building on Central Avenue in Phoenix, where 23 would witness the intricate effects of gentrification firsthand.

Illegal activity and unsafe neighborhoods are a key component of gentrification, says 23. To him, gentrification goes beyond a shuffling of artists. He says it is a cycle in which crime is slowly pushed from one area of a city to another as the police start to enforce the law in areas that begin to be inhabited by wealthier, whiter constituents. 23 says Thought Crime is a perfect example of this - he says despite the fact that there was a police station right next door, he would walk down Central Avenue, near Thought Crime's new home, and see prostitutes and crack addicts. As crime is pushed out of one area, it is followed by the renting families, displaced by increased property values, who can't afford to buy their homes. 23 says he believes that in America, especially in Phoenix, the cycle becomes one not just based on economic lines, but racial ones as well. He says the primary attendees of First Friday are mainly middle-to-upper class whites, while the majority of the area's inhabitants are lower class people of color.

"Artists need to reach out to the people who were there before them," he says. "If that connection is built and fed, we're going to be there a long time."

But the doors at Thought Crime were closed earlier this year, guarded by a graffiti skeleton proclaiming "Thought Crime is dead." A new landlord specializing in turning profits through property investment bought the building earlier this year to convert to office space, 23 says. He adds that if the landlord had decided to keep renting to former occupants of the building, rent probably would've tripled, judging by the sale price. Either way, Thought Crime was forced to search for a new home. It now occupies the Firehouse Gallery a few blocks away.

The Firehouse is now inhabited by lifetime Valley resident Vaiden Boyer. Sitting in a downtown Phoenix coffee shop a few blocks away from the Firehouse, and less than a mile from the home she grew up in, everything Boyer says on the subject of art in Phoenix is preceded by a thoughtful pause. Almost every recollection is accompanied by the hint of stories from the past.

"I think people wanted it to be more popular," she says. "And now that it is, they're asking, 'Is this really what we wanted?'"

Boyer grew up with the art scene. She started going to galleries with her parents as a child, and when she hit her teenage years, she began volunteering at the Alwun House, the oldest alternative art space in Phoenix. Now, as a member of ArtLink's board for the past three years, Boyer spends hours talking to vendors, galleries and Phoenix police getting ready for every event.

To Boyer, offshoots of First Friday, like Tempe's Final Friday, represent the greatest opportunity presented by the city's discovery of the arts: a city alive with art every night. But she's not ignorant to the negative effects of the artistic growth downtown. She says she's watched the complexion of her old neighborhood change, with those who couldn't afford to buy their homes being forced to move elsewhere by rising land values, replaced by more affluent tenants.

"Everybody has some anecdote about how their cousin bought this property five years ago and it's tripled in value," she says. "They're thinking about it from the owner's experience. I think that's great for the people who had the ability to buy five years ago -- but when the market takes off, where does that leave everyone else? It makes it hard for there to be roots, in a city that already lacks roots."

Phil Jones

Director of the Phoenix Office of Arts and Culture, Phil Jones, has been involved with the arts his entire life; first as a piano teacher and now as an advocate.

"Everyone on my staff is an artist," he says. "But we're also administrators in a bureaucracy -- we advocate for artists within the government. We're wearing two hats, essentially."

Jones works at providing culture and art to people in the city. Though he has been involved in arts and politics across the country for 25 years, he says he sees little connection between the two spheres of his life.

Working with groups like ArtLink, Jones is fully aware of the fears of gentrification in Phoenix. The important thing, he says, is to combat gentrification with legislation that will prevent it. Currently, there are a few concrete programs already in place in Phoenix to support artists. The Downtown Artist Storefront program gives building owners downtown grants to work with artists to turn their storefronts into works of public art. The grant is given on the condition that the building is open to the public as an art gallery for a certain number of hours. Jones says more programs to support downtown residents are in the developmental stage

"The city is making a concerted effort to make affordable housing available to everyone," he says.

Jones says not losing sight of the larger picture of the arts community, which includes performance venues and museums, is also critical. Remembering all of those factors helps focus on the government's supporting role in developing culture, he says. Jones says he works with people like 23 and Boyer in groups like Downtown Voices and the Downtown Phoenix Artists' Coalition, in addition to other city agencies, to explore options like rent control and zoning overlays. While the solutions aren't clear, it isn't from any lack of effort on the city's part, says Jones.

"We're doing everything we can to make sure the arts stay a part of Phoenix," he says.

Kimber Lanning

Just a few blocks east of ASU's Tempe campus, Kimber Lanning stands behind the counter at Stinkweeds Record Exchange like she's manning the helm of a ship. In between chatting with customers, taking calls from artists and filling out paperwork, she manages to talk about her other love, Phoenix gallery and performance venue Modified Arts. Lanning is the owner of both.

"I saw that we had a great community of artists with no avenue to express themselves," she says. "I always believe in doing something, not sitting on the couch or moving somewhere else."

Lanning got off her couch in 1987, when she dropped out of the architecture school at ASU to work on Stinkweeds full time, and hasn't looked back since. Stinkweeds has gone from a store offering 16 CDs and Lanning's personal record collection to become a place for band performances and displays of local artists. Still, Lanning wanted to do more and, in 1999, she became the owner of Modified Arts on the corner of Third and Roosevelt streets in Phoenix. Lanning opened the building with a group of volunteers to help her run it, a practice she continues today with a staff of six. The venture has been successful enough to stay open, but is not a source of profit.

"Modified was always intended to be a community resource," Lanning says. "Not a business opportunity."

With the increased attendance at First Friday in the past six months, Lanning says she has actually seen sales go down.

"First Friday has essentially gone from a great community art walk to a block party," she says. "It's hard to focus on showing people around your gallery when you have to keep asking people to stop shouting and tell them to take their 40s outside."

Lanning and a few other gallery owners have switched their gallery openings to the third Friday of every month. While that may provide relief from undesirable crowds, Lanning is unsure of how to avoid what she sees as an inescapable reality -- that of gentrification.

"Artists come in and fix up a part of town that no one else finds value in," she says. "And then they are forced to leave as businesses move in."

Lanning expects an additional challenge from the expansion of ASU to its Downtown campus, a part of the New American University plan proposed by ASU President Michael Crow. Modified Arts sits right by the proposed location and Lanning says she has seen property bought up all around her, and has no intention of leaving.

"I'm going to stay and fight," she says. "There's an organic aspect to the way things developed here, and I think you'd lose that if you just relocated everyone and tried to force something like this. And I think that's important."

Reach the reporter at ben.horowitz@asu.edu.