From under a white tent on Hayden Lawn, members of ASU's American Indian Council sell tacos and fry bread.

In the background, contestants for Ms. Indian ASU and other organization members parade down a runway for the American Indian fashion show.

The event marks the start of ASU's Native American Culture Week, which will culminate this weekend with a powwow on the band practice fields. The week is the only time every year that ASU's relatively tiny American Indian population becomes one of the most visible.

Despite the fact that Arizona has 22 tribal nations, there are only about 1,300 students who identify themselves as American Indian out of the tens of thousands of students at ASU.

Additionally, American Indian students have the highest drop-out rate on campus and the lowest graduation rate -- two facts that have ASU administrators worried.

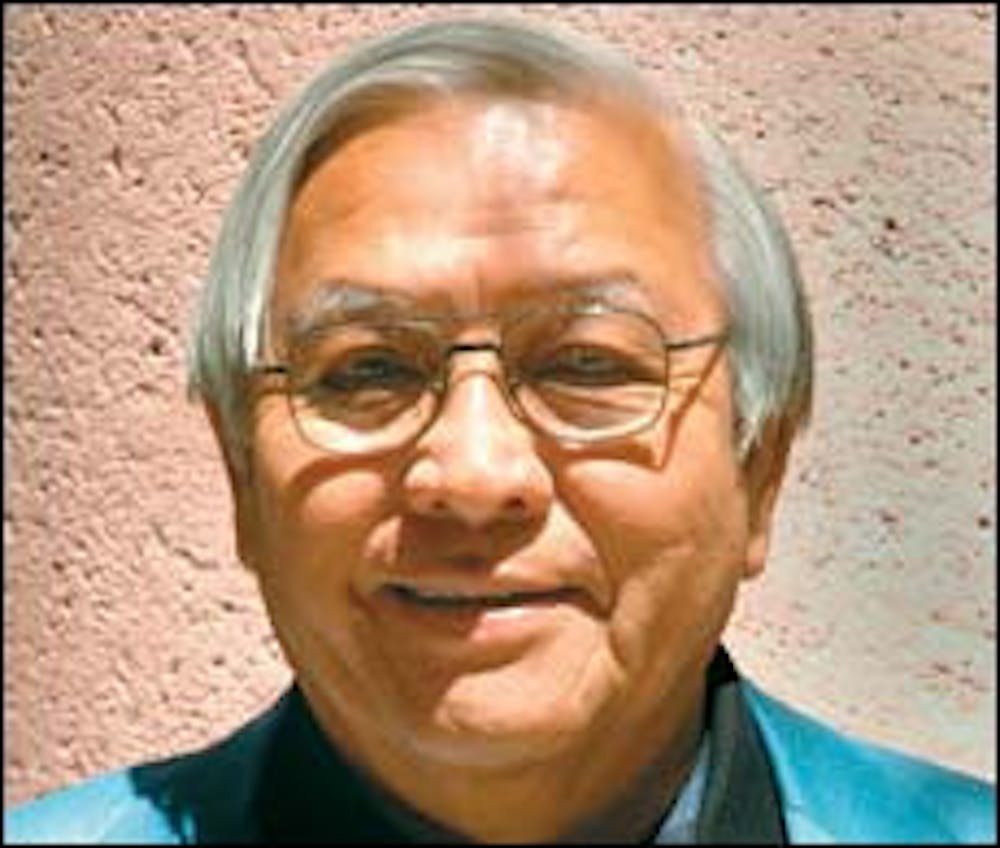

When Peterson Zah took his position as adviser of American Indian Affairs 10 years ago for former ASU President Lattie Coor, there were only between 600 and 700 American Indian students on campus.

Zah, a former president of the Navajo Nation, says Coor made American Indians one of his main focuses during his presidency.

"He said to me 'In my own mind, the most important thing is more Native American students on campus, and once they are here, keep them until they graduate,' " Zah says.

Coor gave Zah an office, a phone and an ASU T-shirt, and put him to work.

First, Zah set out to determine why American Indian students were dropping out in such high numbers. He found that it wasn't because of heavy workload or financial troubles.

"What they said was that the University is just too cold," Zah says. "We don't take time to welcome them or warm up to them. Yet, the University preaches diversity and wants to be a rainbow of diversity."

There are 22 tribal communities in Arizona, occupying about 30 percent of the state's total land. These communities range from the giant Navajo Nation in the northeast corner of the state to the tiny Gila River Indian Community near Phoenix.

The Navajo make up the highest percentage of American Indian students on campus. As Zah points out, some students who grew up on the reservation may have a fear of the transition to the University, especially if all they have known is Navajo ways on Navajo land.

What Zah saw, through his surveys and research, was the need to create a welcoming community at ASU, so that American Indian freshmen would feel like they had a support group the moment they arrived.

One issue in particular was causing some students to drop out before their freshman year even began.

The Navajo Nation stretches into four states -- Arizona, Utah, Colorado and New Mexico. For tuition purposes, however, ASU considers all Navajo as in-state students.

Some people at the admissions office, according to Zah, would not be informed of this and would hassle incoming Navajo students from other states. And sometimes, greeters would be annoyed because it seemed like Navajo students were getting a tuition break.

"My job was to make people aware of this and let young workers know that it was not their job to make a judgment," Zah says. "The land on the reservation was carved into states, but we were there first. The Navajo stood there with question marks on their faces asking 'Why are we putting fences across the land?' "

Support system

Zah's assistant, Jaynie Parrish, graduated from ASU in 2002 in the second class of a revolutionary program that began in 1996.

The Native American Achievement Program is a new scholarship and success program that partners ASU with the Navajo Nation, the White Mountain Apache and the San Carlos Apache. The program is open for any tribe to join.

As part of the program, the tribes choose students to receive full scholarships to ASU. The students who are chosen are heavily monitored during their first two years at the University, with individual counseling and assistance to encourage retention. Students must meet program requirements to get their money every semester.

Since the program began, the number of American Indian students on campus has grown to around 1,300. The same number of new students come in every year, but the University is retaining more.

Parrish credits Zah with the program's success.

"Mr. Zah is really close to the Navajo -- he is so highly thought of," Parrish says. "Many people even think of him as family."

She adds, "A Hispanic group came in here and were amazed at what Native Americans are doing on this campus. It is a real family atmosphere. Everyone wants to help, to contribute and to save a student. There is a lot of concern."

Aaron Woods is a student success coordinator in the Multicultural Student Center and is responsible for administering the first year of the achievement program.

Woods says that before the program, American Indian students were only being retained at a rate of 50 percent or less. Now, that figure is around 75 percent.

"I use the analogy of a battle, and we were losing half of our people," Woods says. "So this has been a significant increase."

Woods says that one of the program's goals is to create a community for incoming students so they know where their support is and how to get help.

"Whether it is a football team or an army unit, within a team, people are more likely to stay together," he says.

Woods and other advisers work with the students to encourage them not only academically, but also culturally and spiritually.

"They know the culture and the language and they can share this wisdom with non-Natives," he says. 'It hasn't been told to them this way in the past, that they have all of these wonderful gifts to share with others."

The program's success is tangible. A report issued by ASU Student Life in 2002 tracking the first five years of the program found that students in the program had, on average, a 14.24 percent higher retention rate than other American Indian freshmen.

Additionally, in three of the five years, students in the program had a higher GPA than other American Indian freshmen.

Unfortunately, as Woods notes, there are limited spaces in the program, mostly based on the tribal income and ability to award full scholarships in a given year. Occasionally the funds arrive late, leaving students in a sticky predicament.

Also, he says that some students do not like being told what to do or being so heavily monitored. They may feel like they are old enough to deal with everything on their own.

"Most students who have classes here will be the only Native student in their class," Woods says. "We are not together enough -- this is why we have socials and events. Togetherness builds strength and provides time to look back at cultural roots. You are Native before you are anything else."

It is important to honor the commitment to educate Native youth, especially since many want to give back to their communities. Woods says he often hears students mention that they want to go back to work on a reservation, or help their people in a city-based job.

"Rarely do you hear a Native student say they just want to make a lot of money and pimp their ride," he says. "They know where they come from and want to give back."

Far from home

Aerospace engineering sophomore Melissa Bryant is a member of the Navajo Nation. She is also the president of NATIONS, a student club that stands for Native Americans Taking Initiative on Success.

NATIONS was started last school year at the behest of the Multicultural Student Center to help tackle American Indian retention rates, which are still lower than the student average. The goal of NATIONS is to create a community on campus for American Indian students, offering cultural and academic support.

Bryant says the Native student drop-out rate may be a bit overblown, as a lot of students in her acquaintance transfer or change to a community college. The University doesn't take into account where students go when they drop out, and many do not leave education all together.

Bryant says students she knows have left ASU for a variety of reasons. Some want to go to NAU or the University of New Mexico because they would be to home. It takes six hours or more to drive home from ASU for students on the Navajo reservation. Some leave for academic reasons. Others just are not happy at ASU.

"I think it is an issue of not feeling connected or feeling a community here. It is a really different atmosphere, and if they don't find a place to fit in, they are not going to stay," Bryant says.

Bryant is from Flagstaff, which borders the Navajo Nation. Many of her family members live on the reservation.

Driving the long stretch of highway through the Navajo reservation, heading north to the Grand Canyon or into Utah, it is hard to see past the roadside stands selling jewelry, blankets and fry bread. But beyond the road lies the real Navajo.

"It is very spread out. There are just little communities spread out by 40 or 50 miles. It is quiet and peaceful," Bryant says.

One of Bryant's friends took an introductory UNI class freshman year. One day, they were talking about stereotypes and one fellow student said that American Indians are all alcoholics, poor and all their money comes from casinos.

Bryant thinks more events on campus geared toward American Indian culture would help educate people about these stereotypes. There is one day during the fall semester and the awareness week in spring that highlight American Indian culture, but she says that is not enough.

Shocking differences

Cal Seciwa pulls out his wallet and flips it open. He rummages through the pocket and pulls out his Native American enrollment card, which makes him an official member of the Zuni Pueblo tribe.

"Some of my people just accept these things," he says. "But others of us wonder why we have to show a card to go to the Indian hospital."

Seciwa is the director of the American Indian Institute on campus. He has been with the institute since its inception in 1989.

Most people, he says, do not understand the uniqueness of the tribal situation.

"There is the stereotype that we live off the government and pay no taxes. I have a pretty thick skin, so I have become more of an educator about these issues," he says.

People are generally not aware that the U.S. government has guaranteed education and subsistence to American Indian nations as the result of treaties and agreements. American Indians are the only ethnic group mentioned in the constitution, giving the president the authority to make treaties with tribal governments.

Seciwa is quick to point out that treatment of American Indian students is usually not a racial issue, nor an ethnic issue, but rather is based in political and legal intricacies.

Seciwa credits former ASU president Lattie Coor with heading the charge to attract American Indian students to campus. According to Seciwa, Coor knew American Indian students and has American Indian friends. He went to NAU, played football against Peterson Zah and ate fry bread.

"We had a lot of critics at first," says Seciwa of the institute. "People said 'Why just Indians?' It was definitely an uphill battle for the first few years."

The American Indian Institute is a support center for American Indian students on campus. Housed in the Engineering Annex building on campus, the institute houses Seciwa, four full-time employees, graduate students and undergraduate students. It provides computers, tutoring, copying, counseling and other resources.

Seciwa says that one of the biggest issues affecting the ASU's retention figures is that American Indian people view education differently than the university norm.

"If a student takes 12 years or 12 semesters to graduate, in the eyes of our American Indian people, they are a success. But in the mainstream, they are not," he says.

Seciwa says education has always been an asset to the mainstream, but until the last 50 years or less, it was an enemy to American Indian people -- a tool to assimilate and erode their culture.

Part of that had to do with boarding schools for American Indians, which began as a way to "civilize" American Indians in the late 1800s and early 1900s. In that time, the U.S. government moved American Indian children thousands of miles from their families, cut their hair (which is a symbol of pride), made them wear "civilized" clothes and forced them to speak only English.

"Only now can Indian people finally map their own educational destinies," Seciwa says. "They know now that they are not here to loose their language or their culture."

How academically prepared the students are when they arrive at ASU is also a big factor, he says.

Most tribal people do not have their own tribal members teaching in schools. Instead, they are often reliant on non-Native, non-tribal members to educate their youth -- people who do not understand the culture or have anything invested in the success and motivation of their students.

On reservations, teachers often come and go, using a few years of teaching reservation children to augment their resumes or acquire professional experience before moving on.

Of course, this is a generalization, and Seciwa says that some students come from academically challenging schools and are quite successful at ASU. He mentions one student who came in with Advanced Placement credits and was in a Master's program by age 19.

"Some, though, come to us having to take sub-100 level courses. They have one hand tied behind their back already, and are set back a year or more," he says.

Another new program is tackling the issue of tribal teaching. The College of Education's Indigenous Teacher Preparation Program synthesizes regular education curriculum with traditional teaching classes. There are similar programs in the College of Law and the School of Nursing.

Seciwa says another concern is that some students may be financially unprepared for the responsibilities of school.

"Employment opportunities on the reservations are nil," he says. "Some families really cannot contribute to a student's education. A summer job is really not an option. The only options for these students are tribal grants and Pell Grants.

Yet, tribes will usually only fund students for eight to 10 semesters maximum, and the average for Native American students is around 12, so many students find themselves short on resources.

Finally, culture shock is always a factor that contributes to drop-out rates.

"Though it is not as much as in my day, with the Internet and technology providing access to the outside world, some still come to us from real traditional settings -- some with no running water or electricity," Seciwa says. "This is especially on remote parts of the Navajo or Apache. But even for those who come prepared, going from a senior graduating class of 100 to a lecture of 300 can be a shock."

Sharing knowledge

Back out on Hayden Lawn, the crowd disperses as the Native fashion show comes to an end. For the rest of the week, the American Indian students and groups will sponsor events highlighting educational, insightful and entertaining facets of American Indian culture.

If Zah, Seciwa, Woods, and students like Bryant have their way, ASU will become an ever more welcoming institution, where American Indian students can foster their culture, learn, and share their knowledge with others.

Reach the reporter at katherine.kelberlau@asu.edu.