Even when he was young, William Calvo knew he was different.

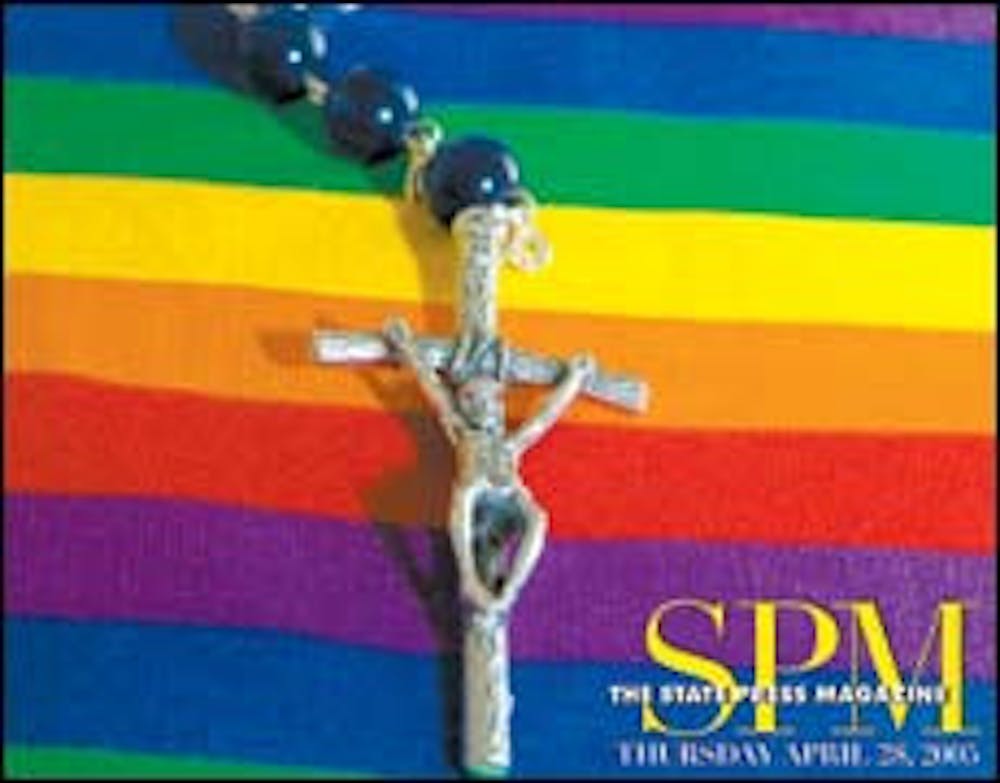

Growing up in heavily Catholic Costa Rica, spirituality and the church always were important to Calvo.

But there was another element to Calvo's personality that also was there, even though he did not know what it was at first.

Calvo was an effeminate child, a bit of an outcast. He liked He-man-type cartoons, not because he wanted to be like the superheroes, but because he was attracted to them.

Calvo was in high school when he began identifying himself as gay.

But there was a problem -- the religion he loved told him homosexuality was a sin.

Calvo's situation is not unusual, says Tracy Fessenden, an associate professor of religious studies at ASU. While the topic has only been discussed for a few decades, there always have been those who identify themselves as homosexual and religious.

But as two ASU students have discovered, no matter how many people have dealt with the issue, reconciling faith with homosexuality can be a long process leading to very different conceptions of the church.

In context

Homosexuality has been at the core of a number of recent conflicts, ranging from the appointment of an openly gay minister to the Episcopalian Church to the election of a conservative pope to discussion about gay marriage in last November's presidential election.

But it is not a new issue, Fessenden says.

She says homosexuality has become of interest lately mostly for political reasons and that people's views of homosexuality can represent a whole set of beliefs that are deeper than one particular issue.

"People who went to the polls based on that issue, I don't think they were so concerned with gay marriage," Fessenden says. "That issue served to crystallize a whole series of opinions and values."

Fessenden says arguments that say the Bible denounces homosexuality are not entirely accurate. There are different conceptions of what homosexuality is now than when the Bible was originally written.

"Most people who quote these texts in support of the anti-gay position are not familiar with their contexts, not familiar with the ancient languages," Fessenden says.

Mark Newman, president of the Phoenix chapter of Dignity and Integrity, a national organization that ministers to homosexual, bisexual and trans-gendered Catholics and Episcopalians, also emphasizes that point.

"When it's placed in the time frame and the mentality of the time, all of those passages can be condemning other issues," Newman says.

While mainstream churches have been slow to change long-held attitudes and policies toward homosexuality, organizations such as Dignity and Integrity have formed to help homosexuals worship in an environment with which they are familiar.

"They feel condemned by their sexuality," Newman says. "They feel isolated."

The Roman Catholic Church does not recognize the group as an official Catholic organization, Newman says, but it does give gay Catholics and Episcopalians a place to worship where they feel welcome.

Many members of the group have gone through commitment ceremonies with their partners. These ceremonies may not be recognized as legal marriages, but the feeling behind the sacrament still resonates with couples who have gone through them.

"Whether the mainstream church would recognize that as a sacramental union is another question," Newman says.

Call to priesthood

Calvo, who is studying for his doctorate in industrial design, once thought he was destined for the priesthood.

"I thought the only way to do good was to be a priest," he says.

So in 1994, Calvo left his home in Costa Rica for a seminary in Italy. While the seminary deepened his faith, it also encouraged him to keep his sexuality in the closet.

"I figured out from an early stage it was a taboo topic," Calvo says. "It's not, 'Don't ask, don't tell,' it's, 'Don't show up.' "

For the three years Calvo spent in the seminary, he was well liked, and even became student body president. And the more time he spent in the seminary, the more comfortable he became with who he was.

"The more I was getting closer to God, the more I realized it was no big deal to be gay," he says.

But Calvo did not tell anyone he was homosexual until 1997.

One day, he was standing inside a church in front of a statue of the Virgin Mary. Mary had always been a "perfect image," Calvo says, of a human used by God for perfection.

However, this particular statue of the Virgin had survived a battle. At one point, someone had scraped a knife across the statue, creating deep scars on one side of its face.

"She was imperfect," Calvo says. "That's me. I'm completely immaculate because of the love of God, but I'm not perfect because of sin."

"I felt it was right and OK and that God wanted me to be gay," he says. "It was an epiphany. I was so happy."

Calvo immediately ran out of the church to reveal his revelation to the rector, who is the head of the seminary. The rector did not share Calvo's joy, telling him that he was just going through a phase.

"At that time, what was supposed to be the greatest revelation of my life turned out to be the biggest nightmare," Calvo says.

From that point, Calvo was assigned to kitchen duties instead of roles that would let him work with children. He was required to take sleeping pills so he would fall asleep early, and wouldn't see other men changing at the end of the day.

Eventually, he was taken to a convent in Rome to talk to psychologists about his "problem." He was depressed and was losing weight. After about three months, the psychologists determined he was indeed gay.

"I was expecting them to say, 'How do you work with this?' " he says. "They said, 'You can't be a priest.' "

The seminary made arrangements to send Calvo back to Costa Rica. His fellow seminarians told his mother was sick and had to be with his family.

However, Costa Rica was the last place Calvo wanted to go. He didn't want to face his family or deal with the anti-gay movement in his home country.

"It was clear this new me had no place there," he says. "I may not be killed by someone in Costa Rica, but I may kill myself."

Instead, he sought asylum in the United States. After living with friends on the East Coast for about two months, he moved to Arizona to be close to other family members who lived there.

One of the first things he did was go to confession, a ceremony in which Catholics admit their sins to a priest so they can be forgiven. He told the priest he was gay.

"He asked if I had any boyfriends or Catholic gay friends," Calvo says. When Calvo said he did not, the priest advised him to meet gay Catholics.

Calvo turned to Dignity and Integrity, who welcomed him. He also started to recognize that the church didn't dictate his faith.

As an institution, the church has made mistakes, Calvo says. But he has distinguished between the institution and the spirituality of religion.

"I think of the church as a human. Humans make mistakes," Calvo says. "In the future, the gay issue will be clarified."

Calvo returned to the seminary in 2003. His new seminary was in St. Paul, Minn., where about one third of the men were openly gay but just as committed to celibacy as their heterosexual counterparts.

He ultimately left the seminary, this time because he realized he could serve his community without being a priest.

Calvo still attends Mass regularly. And while he doesn't think a person needs to subscribe to a specific religion, he says it's important to determine one's own spirituality.

"If God has a plan for that person the way they are created, you cannot force that person to be different," Calvo says. "That's misstating the power of God."

Growing in college

Lauren Lee's family wasn't always religious. But when Lee's mother left an abusive relationship and moved to Yuma, the family turned to a non-denominational Christian church.

Lee, a women's studies and painting senior, was involved in the church community, but something always felt wrong.

"Almost every time I was at church, I cried," she says. "There was a very deep-seated sense of shame in me."

By the time she started at ASU, she was slowly backing away from the church. She had always felt spiritually separated from some of the other members of her religious community, and the new people she met at ASU started making her question some of the things she had accepted as truth.

She was especially wary of some of the religious debates she got into with fellow students.

"We all believed strongly this was the right way," Lee says. "There's something wrong with this picture. I can't believe I'll fall off the face of the earth because [I] choose the wrong denomination."

At the same time, Lee began noticing how diverse people at ASU were compared to Yuma.

"You get bombarded with diversity," she says. "I don't think I had ever met a lesbian until I went to college."

But it wasn't until a man she was dating suggested she should try relationships with women that Lee seriously considered that she might be a lesbian. Lee had tried to have relationships with men for eight years, but she says it had always felt cheap.

The first time she was with a woman, she felt emotion in what she was doing.

However, homosexuality was not acceptable to the type of Christianity she knew. Lee says she felt there were two conflicting spiritualities within her.

"I went into panic, thinking I had strayed and surrounded myself with sinners," Lee says. "It was a choice between giving up my sexuality forever or you walk without God."

Lee's family was also scared for her, she says. Her sister once told her she would not let her children play with any children Lee might one day adopt if they were brought up in a "sinful lifestyle."

Eventually, Lee's grandmother, whom Lee considered her spiritual adviser, assured her granddaughter that she could make her own decisions.

"That was scary for me because it was walking away from the choice she made for me," Lee says.

So, Lee had to determine what spirituality meant on her own. She could have lived according to mainstream Christian values in a relationship with a man, she says, but she would not have been able to have sexual feelings for him. Or she could accept her homosexuality and decide for herself what religion meant.

"I believe religion can scare you asexual," Lee says. "I could walk away from sexuality, be within a heterosexual union, but be asexual."

She ultimately decided that she deserved to feel love.

"I've erred to the side of love and compassion, what I believe are the central tenets of Christianity," Lee says.

Today, Lee does not attend organized church services. She says she feels resentful toward religious institutions. Nor has she kept in touch with the church members she knew in Yuma.

"There was no questioning going on," she says. "They were just blindly accepting what people were saying."

She says she does not often pray, but she does continue to read the Bible, mostly so she knows what she is talking about when debating what it says about homosexuality, but also for the message.

"I'll read the Bible, but I'll only read Jesus' words," she says. "The things that Jesus Christ lived for were phenomenal."

Next steps

The topic of religious homosexuals likely will be around for a long time to come, Fessenden says. Conservatives and liberals alike continue to stick to their own views about the topic, and compromise doesn't seem likely.

"It separates people from one another," Fessenden says. "I don't think it's going to go away."

Calvo is more optimistic.

His experiences in the United States have proven to him that there are people exploring how spirituality is different for various groups of people. The church has traditionally been male-dominated, but it is slowly embracing women, homosexuals and others.

"That's the church I pray for," Calvo says. "And I know I may never see it, but I know it will come."

Reach the reporter at amanda.keim@asu.edu.