Swarming with ocean species, coral reefs cover less than 2 percent of the seafloor, even though they are the most diverse marine ecosystem in the world, according to the Smithsonian.

The severity of an issue can sometimes seem minimized when it is not directly affecting an area. When it comes to coral reefs, people in Arizona may be less aware of the exponentially decreasing rate of healthy coral, simply because the state is not exposed to any coast.

However, two ASU student artists hope to bring this issue to light with their MFA thesis exhibitions.

Ceramics, poetry and the science of seafloor mapping are brought together in two exhibitions, “Bleached” and “Opallios,” in the effort of saving the planet one plastic bag at a time.

Brandi Lee Cooper, a ceramic MFA candidate at the ASU School of Art in the Herberger Institute for Design and the Arts, showcases “Bleached,” a ceramic-based art exhibition that presents humanity’s effect on coral reefs.

The exhibit is made up of a 14-piece ceramic installation that represents a coral reef that has been bleached and suffocated by plastics that have ended up in the ocean.

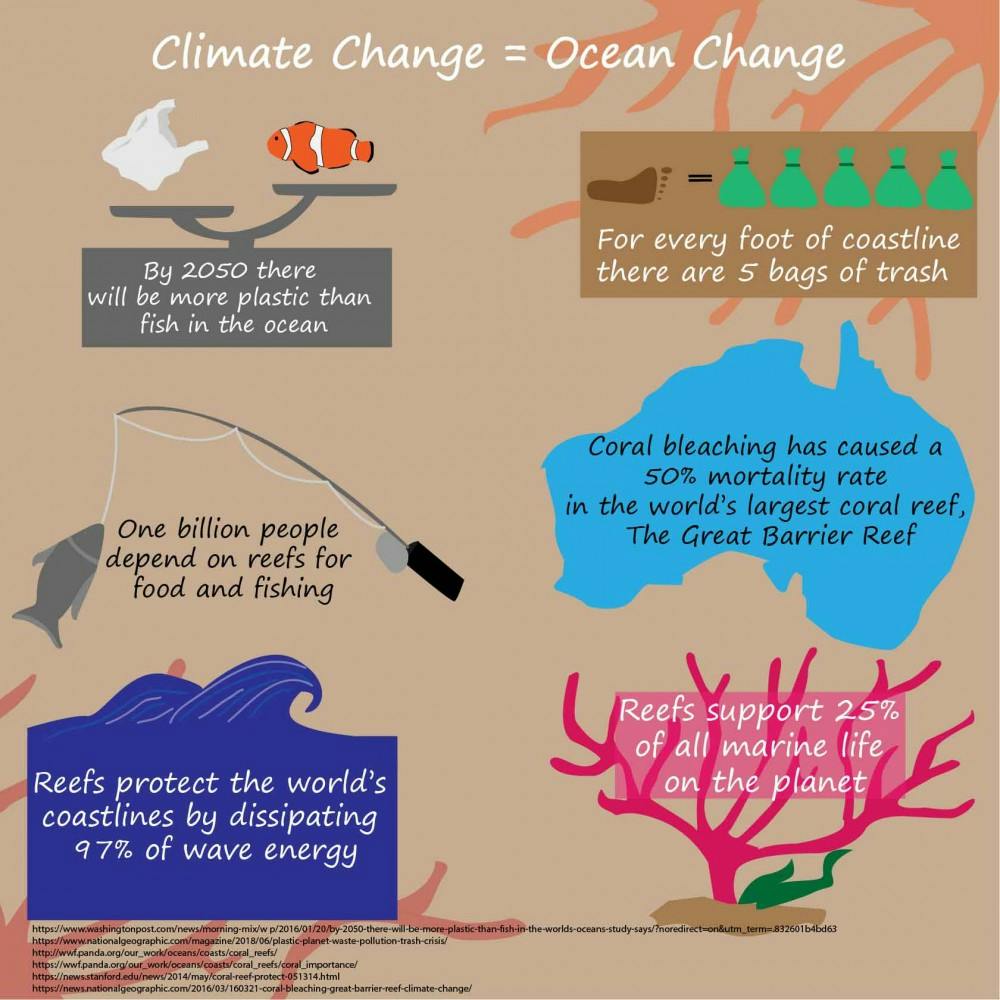

“We're losing coral reefs, which are one of the most biodiverse ecosystems in the world, at an alarming rate,” Cooper said. “Climate change, overfishing, pollution these are all really impacting coral reefs — as well as plastic.”

These two exhibits, both of which have opening receptions on Feb. 15, aim to display an artistic representation of coral reefs and the conservation of the ocean. The work of these artists intend to educate the public about the current state and health of these marine systems that impact so many people, even the ones that live in the middle of the desert.

Due to rising temperatures, these corals are being weakened to the point where they lose all their color and become "bleached," according to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration.

Cooper said once these corals become bleached it doesn’t mean they are dead. It is possible for corals to survive a bleaching event if local conditions improve, such as water temperatures and pollution decreases.

She said when plastics come in contact with coral, wrapping around them and cutting open their tissues, it starves the coral of vital oxygen and light and releases toxins enabling bacteria and viruses to invade, ensuring death.

Cooper said that this installation, located at the ASU Step Gallery in Phoenix, is a physical manifestation of the devastating impact humans are having on coral reefs. She hopes it reminds people of humanity's connection and responsibility to each other.

"Art is just another way to engage people about science and what's happening in the environment," she said.

Lizzy Taber, teaching assistant in the School of Art, showcases “Opallios,“ an exhibit that blurs the line between science and art and blends poetry with the visualization of the seafloor.

She said that she felt inspired about ocean exploration and seafloor mapping after working with researchers from the Schmidt Ocean Institute, during her art residency program.

"I think the ocean affects everything," Taber said. "All that we do, it affects the environment so much, and we affect it so much."

Taber said she uses poetry with bathymetric maps in her work, which are like topographic maps for the ocean floor, to reveal the poetic metaphor of how unknown the ocean still remains.

“We actually know more about the moon and Mars than we do our own planet,” she said.

Even though Taber’s "Opallios" opened Feb. 11 at Eric Fischl Gallery in Phoenix, its opening reception will be on Feb. 15.

Cooper and Taber said they are donating a portion of their proceeds from their exhibitions to University of Miami’s coral restoration program, Rescue a Reef.

Dalton Hesley, a senior research associate at the University of Miami, has communicated with Cooper and Taber regarding their interest and support of Rescue a Reef.

"The fact (is) that all life kind of stems from corals and that without them, we're all at risk," Hesley said.

He said Rescue a Reef was developed beyond just a research lab so it could be given more of a spotlight and better connect with the local community.

"We're actually growing these threatened coral species by the thousands offshore in these underwater nurseries," he said. "(We) transplant them to local reefs as a way to rebuild (them)."

Taber said the ocean can be out of sight, out of mind for a lot of people.

"If anyone who lives in the desert could take just a moment to contemplate, think about the ocean and reflect on the power it has over us and how much we're affecting it, I think that would be successful," Taber said.

Reach the reporter at ssalahi@asu.edu or follow @mynameissamia on Twitter.

Like The State Press on Facebook and follow @statepress on Twitter.