In the final years of World War II, trapped amid the starvation and squalor of Poland’s Lodz ghetto, 13-year-old Abraham “Abramek” Koplowicz hunched over his school notebook, scribbling down poems that documented the reality of life as a Jew under German occupation.

Stashed in the attic of his family home, his works survived the war — their eloquence and profundity shocking Polish literature experts for years to come. Koplowicz, sent to Auschwitz with his parents in 1944, wouldn’t live to see his 15th birthday.

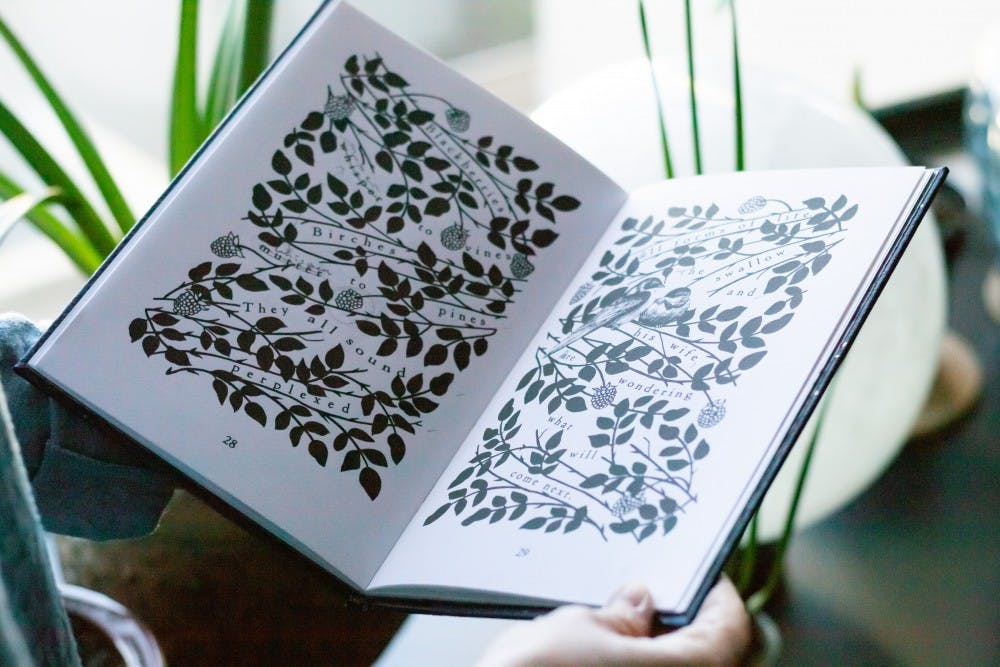

Now, nearly 80 years after Nazi Germany invaded Poland, the ASU Library has acquired the first published English translation of Koplowicz’s poetry in the form of an artist book by ASU alumna Kelly Houle. The poems come as part of a set of artist books by Houle, all acquired by the Library through the ASU Department of English’s Lamberts Memorial Rare Book Fund.

Brittany Lewis, communications specialist for the ASU Library, said the library is proud to house Houle’s unique books.

“Not only are they beautifully intricate works of art that you can hold often in the palm of your hand, they provide new and original ways of exploring a piece of literature,” she said.

Houle, who graduated from ASU in 2005 with an MFA in creative writing, said while Abramek’s poetry highlights just one story, his messages are representative of the millions of lives lost during the Holocaust.

Houle will read Koplowicz's poem "A Dream" at the commemoration on Jan. 29 in honor of International Holocaust Remembrance Day.

“I think it's extremely important that people realize and understand the humanity that was lost in that event,” she said. “Abramek was one of six million people, and it makes you wonder how many others there might have been. How many other children had this interest in literature and perhaps could have gone on to do great things?”

A Smithsonian article published in 2018 stated that while Americans largely believe Holocaust education is important to prevent another similar tragedy, there are large “fundamental gaps” in Americans’ knowledge of that history.

Anna Cichopek-Gajraj, an associate professor at the ASU School of Historical, Philosophical and Religious Studies who specializes in Jewish and Holocaust studies, said studying the Holocaust is vital — particularly at large, public institutions like ASU.

“I think that in this environment, now, it feels that it’s more important than ever that my students learn about how society works in times of crisis, so that they actually see the signals,” she said. "So I think it’s absolutely vital that the students understand the world they live in — that they understand the dangers of certain processes and the danger of crises — as we live in right now.”

Cichopek-Gajrajsaid Koplowicz was 10 years old when the Lodz ghetto opened in 1940, his age making him just barely eligible for work.

It was under the next four years of German occupation that Koplowicz’s writing prowess was discovered, as he spent what little free time he had, when he wasn’t forced to labor in a shoemaking workshop, entertaining his father and his coworkers with poems and satirical skits.

“I think he was a witness to the suffering of others when he himself was in the same situation,” Houle said. “It's truly remarkable. When you think about the age of 14, how much are you thinking of the suffering of others and observing what's going on around you and recording it in this insightful way?”

Cichopek-Gajraj said Koplowicz survived numerous waves of Nazi killings, including the gassing of around 50,000 people from Lodz in early 1942. Then, the following September, the Germans ordered the gassing of 20,000 vulnerable Lodz residents, many of whom were children.

This time, she said, Koplowicz’s age was what saved him.

However, Koplowicz would not be spared when his family was forced to board the last death camp transport from Lodz in 1944. His mother was immediately taken to the gas chambers upon arriving in Auschwitz, while Abramek and his father were taken to the forced labor camp.

Koplowicz’s father left him in the barracks in an attempt to spare the boy from the deadly work, but returned to find the barracks empty. All those left inside, including 14-year-old Abramek, had been taken to be killed while the workers were away.

Audio recording by: Diana Dudurkaewa — English translations copyright Sarah Lawson and Małgorzata Koraszewska 2019 — Poems taken from “A Dream: Selected Poems by Abramek Koplowicz” by Kelly Houle — Illustrations copyright Kelly M. Houle 2019

Houle said the devastating nature of Koplowicz’s story made her work almost unbearable at times.

“This was the most difficult project, emotionally, that I've ever done,” she said. “I felt like, for the last two years when I worked on these things, I (was) kind of almost on the verge of tears just perpetually thinking about it.”

Koplowicz’s father survived the war, eventually marrying fellow Lodz survivor Haya Grynfeld. It was Grynfeld’s son, Eliezer “Lolek” Grynfeld, who discovered his step-brother’s poetry that was rescued by his father after the war, and swore to preserve it.

Houle said she was in contact with Lolek throughout her process, and the fear that she wouldn’t finish the book in time for him to see it loomed over her.

“He's over 94 now, and every day that we were printing the book, my husband and I painstakingly set the type. We printed each page, put all the letters back one by one, printed another page, and it took us months — close to a year probably — to do all of that,” she said. “And every night I would lay there in bed going, ‘I hope we get this done, and I hope we get to give this to him. I hope he gets to see it done.’”

Cichopek-Gajraj said the power of Koplowicz’s poetry lies not in what it did for him, but in its potential for future generations.

“I don’t believe that art could save Abramek," she said. "But I think it saves us."

Reach the reporter at mrobbin9@asu.edu or follow @MelissaARobbins on Twitter.

Like The State Press on Facebook and follow @statepress on Twitter.