According to the Center for Disease Control and Prevention, people are more susceptible to certain diseases depending on their sex. However, there is a sex bias in the data currently available to researchers.

Melissa Wilson Sayres, an assistant professor at the ASU School of Life Sciences, researches the evolutionary history of sex chromosomes and the variation in mutation rates between genetic males and genetic females.

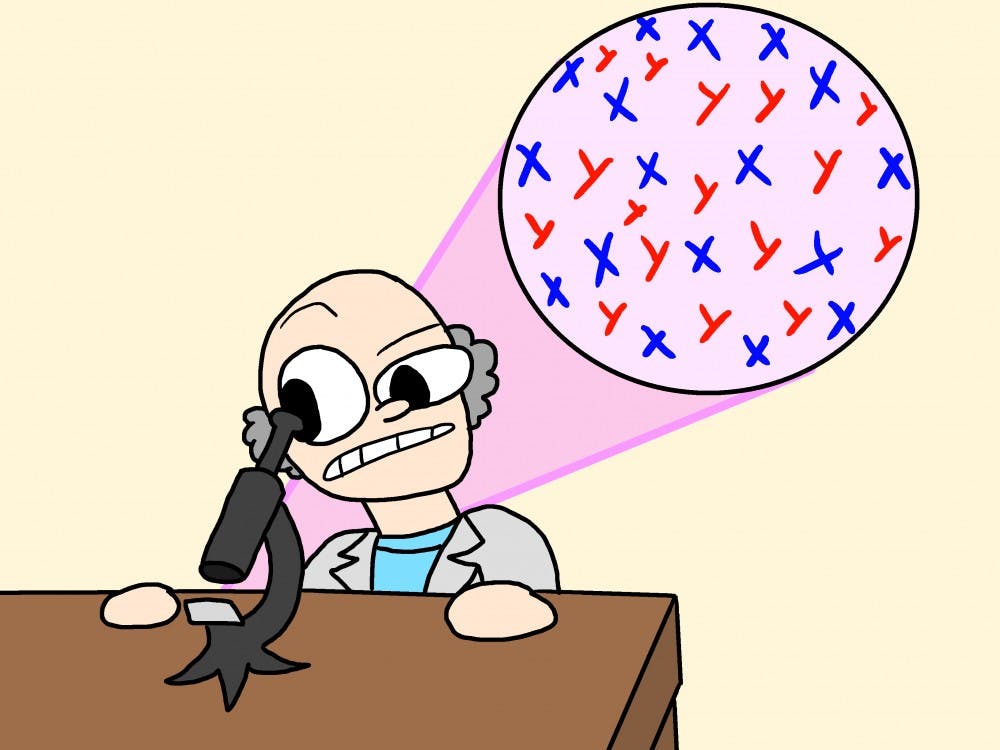

The sex chromosomes in mammals are identified as X and Y chromosomes. Wilson Sayres said research of human sex chromosomes is sex-biased, meaning the majority of the data collected comes from genetic males.

Most clinical trials that have looked at human sex chromosomes have been done on genetic males with the assumption that whatever is applicable to them is applicable to everyone else, Wilson Sayres said.

Although there are some sociopolitical reasons as to why the testing is sex-biased, Wilson Sayres said it's largely because it reduces the number of variables when testing.

Wison Sayres also works to educate the public on the difference between sex and gender.

“It’s not gender identity. It doesn’t bring in culture — it doesn’t bring in the social context and how people are expected to behave,” Wilson Sayres said. “I’m interested in the genetic aspect of it.”

Among other projects, Wilson Sayres is collaborating with researchers at the University of Colorado, which recently established one of the first clinics for transgender youth.

Wilson Sayres said studying sex variations is important because people are more susceptible to certain diseases based on their sex.

She also said that it was not until 2015 that the National Institute of Health decided that sex needs to be considered as a biological variable in disease research.

Abnormalities in the number of chromosomes result in disorders like Down syndrome, which is the result of a person being born with an extra chromosome 21. However, variations in the number of X and Y chromosomes largely results in subtle abnormalities.

Wilson Sayres said research usually excludes the X and Y chromosomes in order to reduce the number of variables while testing.

“They don’t fit the assumptions of regular chromosomes," Wilson Sayres said. "I think it’s largely out of convenience.”

Most people are born with two nearly identical copies of each chromosome. However, this is not true for the X and Y chromosomes. Most genetic males are born with an X and a Y chromosome, while most genetic females are born with two X chromosomes.

Wilson Sayres said it’s important to understand human genetic variations and the correlations between diseases and genetics.

“At a minimum, we have to include (X and Y chromosomes) if we want to be comprehensive in our analysis of the genetic causes of disease," Wilson Sayres said.

Since diseases have sex biases, studying only genetic males provides incomplete data.

“It’s important for disease studies, because there’s so much sex bias in diseases like cancers and diabetes,” Kimberly Olney, a Ph.D student studying evolutionary biology and research technician working with Sayres, said.

Olney’s dissertation as a Ph.D student will focus on the deactivation of X chromosomes. Even variations in some regions of the X and Y chromosomes can cause mutations.

Daniel Cotter, a senior studying biological sciences also working with Sayres, said that regions of the the X and Y chromosomes are often excluded from the final results of studies because researchers think it will confound their studies.

“The autosomes are easier to study," Cotter said. "Often times X and Y are thrown out or chromosomal regions of X and Y are thrown out in studies."

Wilson Sayres said funding to study sex variation as a biological variable has only recently been made available. Because of this funding, her lab has started studying the possibility that variations in X and Y chromosomes can cause diseases like cancers.

Wilson Sayres also said interest in studying the correlation between variations in human sex chromosomes and diseases is growing. She will be attending a conference highlighting sex differences in medicine at Stanford University on Feb. 21.

Clarification: A source's name has been updated to maintain accuracy.

Reach the reporter at jicazare@asu.edu or follow @sonic_429 on Twitter.

Like State Press on Facebook and follow @statepress on Twitter.