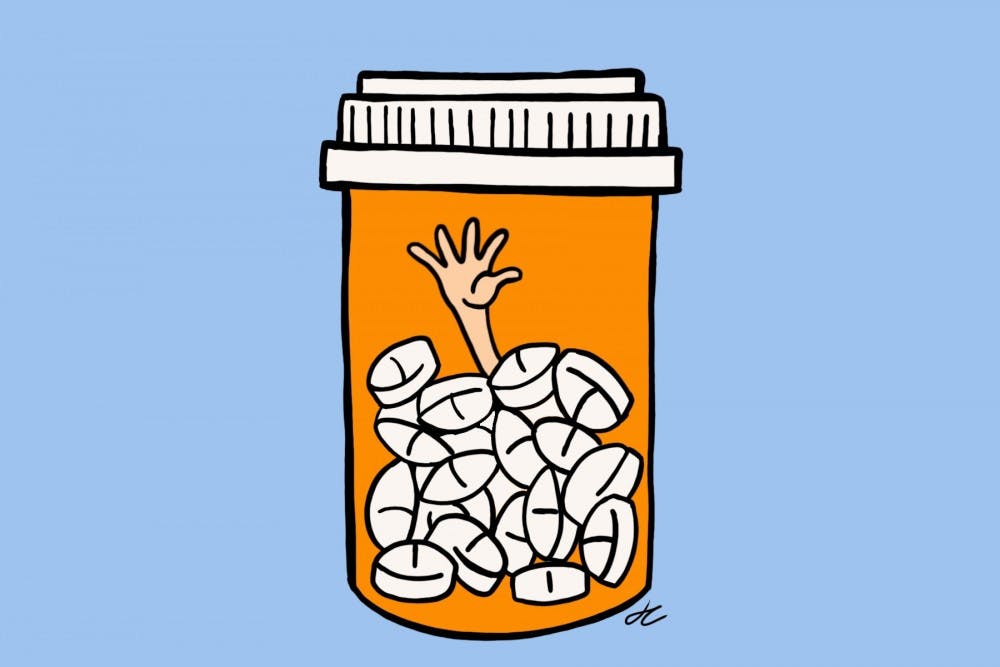

On Oct. 26, 2017, President Donald Trump declared the opioid crisis in the United States a public health emergency, calling it “worst drug crisis in American history.”

The Trump Administration’s current plan for combatting opioid addiction involves “really tough, really big, really great” advertising, channeling funds from Medicaid into rehabilitation facilities and building the wall to prevent the inflow of heroin from Mexico into the United States.

These solutions handle the aftermath of addiction by facilitating recovery and making it more difficult for Americans to obtain illegal drugs, but does not address preventative measures.

The largest demographic of opioid abusers are young adults between the ages of 18 and 25 years, making college-aged students the most susceptible to addiction.

Opioid addiction often begins, legally, when patients are prescribed narcotics as painkillers. However, approximately 16 percent of college-aged individuals reportedly used prescriptions that were not prescribed to them.

In addition to making it more difficult to obtain illegal opioids, it would stand to reason that there should be a proposed solution to the overprescription of opioid medications as well.

Cris Wells, the senior program director of health programs in College of Nursing at ASU, said that the opioid crisis affects a multitude of people.

“A year ago last month, my ex-son-in-law had custody of my grandchildren, and he overdosed when he had them,” Wells said. “The struggle that he and the family has gone through has really been a nightmare.”

In 2014, approximately 61 percent of drug overdose deaths were due to opioids, making it the majority of the nearly half a million drug-related deaths in the U.S. at that time.

Many college-aged people are exposed to prescribed opioid pain medications, as it is common for drugs such as oxycodone to be prescribed for wisdom tooth extractions. Following procedures like this, it is not uncommon for teens to want to continue using the medication.

In 2005, it was reported that 40 percent more high school seniors were using oxycodone than they were three years prior.

“Going back to the root of the cause, obviously it started somewhere, and for (my ex-son-in-law) he was prescribed pain pills for a dental procedure,” Wells said. “Usually it’s not a dentist but another physician that prescribes a pain medication for an accident. It starts out probably very naïvely and after that, depending on the person and their personality and their previous situations that’s how that happens.”

The number of prescription opioid painkillers that were sold to medical institutions nearly quadrupled from 1999 to 2015, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the most common of which being methadone, oxycodone and hydrocodone.

According to the National Institute of Drug Abuse, 80 percent of heroin users began their addiction by misusing prescription pain medication.

The Healthcare Compliance program at ASU is introducing the issue of opioid addiction in the classroom. It explores alternatives to prescription opioids, such as seeing a pain specialist or a chiropractor, and other solutions fall within healthcare regulations and help to solve the problem of overprescribing painkillers.

The opioid crisis requires more than just aftermath-oriented solutions to addiction. If more resources were directed towards solving the root of the problem, the rates of young people abusing drugs are likely to decrease.

Reach the columnist at kalbal@asu.edu or follow @KarishmaAlbal on Twitter.

Editor’s note: The opinions presented in this column are the author’s and do not imply any endorsement from The State Press or its editors.

Want to join the conversation? Send an email to opiniondesk.statepress@gmail.com. Keep letters under 500 words and be sure to include your university affiliation. Anonymity will not be granted.

Like The State Press on Facebook and follow @statepress on Twitter.