Zachariah Webb, Normal Noise’s former editor-in-chief, is perplexed.

He still isn’t sure, five months later, why Barrett, the Honors College censored the magazine’s artwork depicting a nude female form.

Webb and the other founding editors of the magazine, which is produced and funded by Barrett, had just graduated from ASU when they were told administrative officials would not allow the magazine to be distributed.

Normal Noise, the publication these students started in 2012, is a biannual magazine that features long-form journalism, short stories and artwork. The latest issue, which was printed at the end of May 2016, featured student work, including short stories and paintings.

ASU fine art alumna, Annalisa Macaluso, produced a painting of a faceless nude female figure taking a photo in a mirror with a cellphone that was originally commissioned by Normal Noise for a previous issue but was held to run in Normal Noise's spring edition.

The painting was initially approved by the magazine’s editorial staff, and then it went to print.

However, when staff members went to pick up the copies of the magazine, they were met by Ashley Brand, a manager of student services at Barrett. The editors said she refused to allow the staff to pick up the magazines for distribution.

Webb said Barrett officials did not tell the editorial staff of the magazine about any problems with the content until after the issue’s 500 copies were printed and that this was the first time they received opposition from Barrett regarding the magazine's content.

“The trouble arose when, at the start of summer recess, two of our editors went to pick up the issues from the Barrett administration office,” Webb said. “We were told the issue was being withheld — without further explanation.”

Officials from Barrett refused to comment on the issue.

Out of nowhere

It was a move that surprised the editors.

After Barrett officials contacted the magazine’s faculty adviser, the staff learned that Macaluso’s artwork was the reason for withholding the issues and were told the entire magazine needed to be reprinted with a new piece of artwork.

“This act is, in the eyes of the founding editorial board, not only a clear case of censorship against the free expression of ideas within a university setting but also a violent attempt to police the female form and voice,” Webb said.

Normal Noise editors pointed to another Barrett publication, Lux Magazine, as evidence that nudity was not prohibited from magazines produced within the school. The latest issue of Lux contained a photorealistic charcoal drawing of a nude woman on a bed.

The editorial staff of Normal Noise believed Lux had set the standard for what they felt they could and could not do.

“We, perhaps naively, assumed that Lux had set a precedent that would allow for the publication of Macaluso’s piece,” Webb wrote in a preliminary email.

The piece produced by Lux featured the woman laying down with her breasts exposed, looking up at the viewer.

“Perhaps Dean Jacobs is partial to charcoal drawings over oil paintings,” Webb said.

The precedent

Those involved said that Barrett has not been consistent with its censorship of nude art.

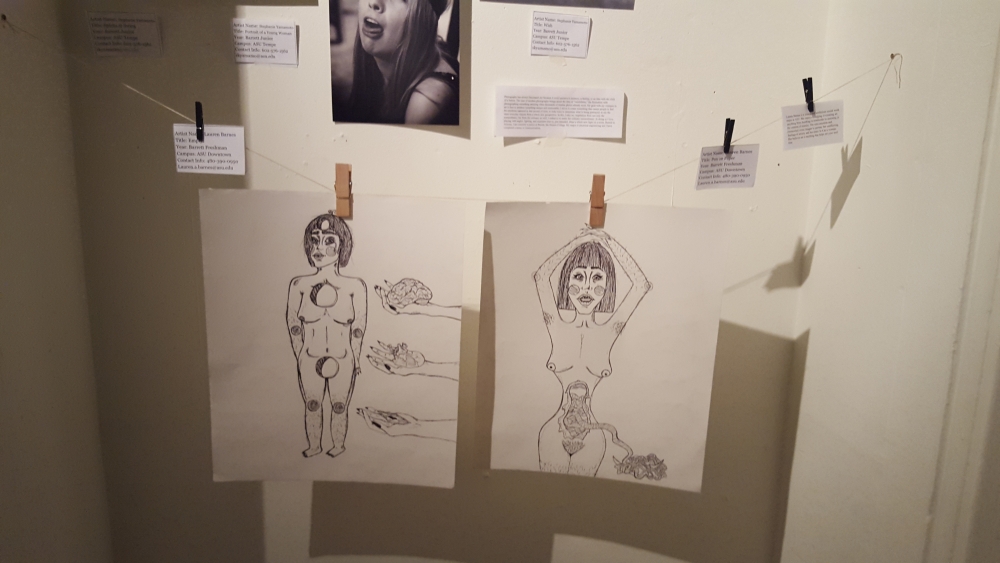

Not only was the Lux photo published, but a large selection of nude art was displayed at Barrett’s student art showcase in downtown Phoenix during spring 2016.

Lerman Montoya, a Barrett student and journalism sophomore, was one of the artists whose nude artwork was featured in the showcase.

He said he sees the censorship of the Normal Noise piece as a double standard on Barrett’s part, due to the inconsistencies of the censorship from different publications, regardless of the reasoning used.

“I think if it’s art, in any way, shape or form, it shouldn’t be censored,” he said. “Especially coming from Barrett where, if we look at literature as an art form, we read explicit content. We read about women’s bodies and about death and murder and suicide and seeing artwork that is illustrated on a canvas rather than put into words is just as important for intellectual growth.”

Montoya suggested that the art showcased in Downtown Phoenix may have been acceptable because it was shown in a public light, at an art district, where nudity is more commonly accepted.

“I think that people like to sexualize bodies and assume that it’s sexual,” he said. “It’s just anatomy on a canvas — that’s not sexual. If you look at a child’s body, and you’re not a pedophile, you’re not going to see it in a sexual way, it’s just a body. This piece was a painting, and it should be regarded as just that — a painting.”

Lauren Barnes, a Barrett student and public service sophomore whose nude artwork was also featured in the showcase, said she thinks the temporality of the showcase may have affected the decision not to censor her work.

“It was downtown, and it was just for one night, and it doesn’t really make sense, but Normal Noise and Lux have Barrett’s name on them and are printed — it’s very definitive,” she said.

While Barnes said she understands both sides of the argument, she doesn’t agree with the censorship and thinks that these inconsistencies shed a negative light on Barrett.

“I think the administration or someone wants to create a safe space and doesn’t want to trigger anyone, but Barrett is supposed to challenge you,” she said. “I understand if ASU as a whole would do something like this, but for Barrett to consider themselves at this forefront as an honors college to help students grow, it doesn’t make sense.”

Barnes said this censorship closes doors on people’s creativity, which is the opposite environment a university setting should provide for student artists. She doesn’t think artists should have to think about censorship in a field that is designed for self-expression.

"We don’t see it as pornographic"

Amy Medeiros, the founding design editor of Normal Noise, agrees.

“We don't see it as pornographic or offensive, and nobody flagged us or told us we couldn't publish this,” she said.

Medeiros said she still isn’t sure why the piece was censored.

“I don’t think any of the content was something an adult would say ‘I'm offended. I can't face the rest of my day because of this,’” Medeiros said. “It would have been nice to have a bit more institutional support and a little more trust from the administrators.”

This is also a blow to the creative freedom of artists in Barrett, she said.

“This is your community, and you’re a part of it, but the people leading the community at an administrative level don't believe your work should be seen or heard,” Medeiros said.

New editors, same conflict

When the fall semester began, Evan Anderson became the new editor-in-chief of Normal Noise, inheriting the responsibility of meeting with Barrett administration to figure out what had gone wrong with the spring issue and how it could be fixed.

“They thought the painting was too obscene to be in a Barrett publication,” Anderson said. “They considered it obscene and verging on pornographic.”

He said that during a meeting with the new Normal Noise editorial staff, Barrett dean Mark Jacobs called the painting “pornographic.”

“He thought that the Lux image was more appropriate than ours,” Anderson said. “His logic was that the painting was situated in the Western history of art, and the pose could be traced back (through history). His argument was that ours wasn't.”

The meeting ended with the declaration that the magazine could not run the image.

“I don’t think that it was okay, but we’ve given up on trying to (publish the piece),” Anderson said. “We’ve reached an agreement to move on.”

He added that the decision was not made lightly, but with Barrett funding the publication, the staff had few options.

“A lot of us think what happened wasn't necessarily okay,” Anderson said. “That area is still really murky, but we made an agreement with the dean, and I think we’re on the same page.”

Nearly six months after the magazine was supposed to be released, the printed copies remain in bureaucratic limbo, locked away in a Barrett administrative office.

Anderson said numerous ideas have been proposed on how to publish the magazine without the artwork, but none have made it past Barrett officials.

“The printer suggested covering it with a sticker,” Anderson said. “The dean’s office didn't like that idea because it could be removed.”

However, he added that his staff was dedicated to releasing the magazine due to the amount of work that went into it, regardless of how long it takes. The estimated cost of reprinting the magazine, former editors said, was at least $3,000.

The consequence of the art

Annalisa Macaluso, the artist, said that she was shocked to find out that her piece was censored.

“The whole thing has just a little bit divided me because I’m not in school, and I just don’t think that way anymore, but (the piece) just feels so tame to me that the thought didn’t even cross my mind when I was doing it,” she said.

Macaluso said she didn’t think the piece was overly sexual, especially because the subject remained faceless, not looking at the camera.

The painting was created to run in the internet controversies edition of Normal Noise, and Macaluso said the idea behind it was to highlight the lack of privacy the internet provides. She said she found the image that inspired her painting on a Reddit forum and wanted to illustrate how easily accessible nude images are.

“It’s something that is so personal, sending a nude image to someone that you care about, and that can so easily go awry,” Macaluso said. “Then nobody starts to think of it as romantic anymore. It becomes porn then, even if the photographer did not intend for it to become porn. (The piece) was mostly about anonymity — that it could have been any girl, it could have been any person.”

Macaluso expressed concern for the creative freedoms of other students at ASU and colleges in general. She addressed presidential candidate Donald Trump’s sexual assault comments and the lack of censorship in the media’s coverage.

“The news can say the word 'pussy' on the air 10 times in a row and this thing got censored?” she said. “It’s so weird.”

The piece was never intended to be provocative, Macaluso said. It was designed to show the realities of modern life.

“The piece, in general, is just supposed to represent a kind of frivolity of how such graphic imagery can be passed around without consequence,” Macaluso said, “and it turns out, there was totally a consequence.”

Correction: A previous version of this article said that "Normal Noise's" Internet issue was held from production. "Normal Noise's" Play issue is actually the one being held from production. The artwork created by Annalisa Macaluso was originally commissioned to run in the Internet issue, which was published in the fall of 2015, but it was later held for the never-released Play issue, which was meant to run in the spring of 2016.

Correction: A previous version of this story incorrectly said the Barrett deans were granted a review before printing, this story has been updated with the correct information.

Clarification: A quote involving the prior review that "Normal Noise's" Play issue underwent has been removed to clarify the process of production at the publication.

Editor's note: Amy Medeiros and Zachariah Webb worked for The State Press in previous semesters. However, they did not contribute to the writing or editing of this article.

Reach the reporters at aegeland@asu.edu and ckmccror@asu.edu or follow @alexisegeland and @ckm_news on Twitter.

Like The State Press on Facebook and follow @statepress on Twitter.