It was a typical Sunday afternoon, and I was catching up on my email. As I typed out response after electronic response, I began to notice a pattern in my language: phrases like "I just wanted to let you know," "I'm sorry to bother you but" and "I know how busy you are" continuously reappeared in my writing.

The phrases I saw repeated in my writing — tentative phrases expressing a desire to be unobtrusive — are not in and of themselves bad. After all, in interpersonal communication, politeness is an asset. The use of language qualifiers, words that serve to reduce the intensity of a statement, can be important when it is necessary to communicate doubt or express agreeableness. In academic writing, it is often requisite to "hedge" language in order to prevent overgeneralization or false claims.

Despite this, the overuse of qualifiers can undermine a message and make its speaker or writer sound as though he or she lacks confidence.

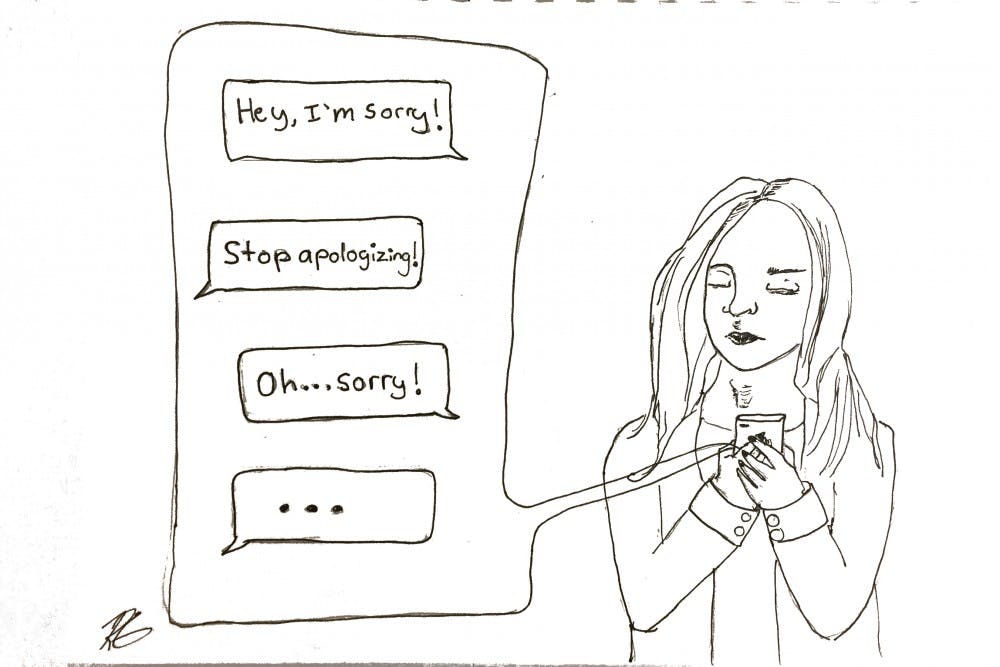

Unfortunately, I realized that my writing clearly demonstrated this principle. Unlike what my writing indicated, I didn’t “just want to check in,” I actually wanted to ask a meaningful question or talk about something pressing. When I corresponded with professors or classmates, I shouldn’t have felt the need to apologize for bothering them with an email about an important issue. After making assertive statements, I often followed up with “if that’s okay?” or “if you think that’s a good idea?” when I should have just stated my honest opinion and let it be questioned on its own.

As I began to analyze the way I was communicating, I was struck by the fact that I was slowly cutting myself down with my own words. I sounded timid, apologetic and passive when I wanted to sound opinionated, driven and capable.

I decided that, for one week, I would ban the word “just” from my email vocabulary. I would only apologize when I had reason to do so, and I would state my opinions as firm opinions rather than as questions seeking approval.

My self-censorship of unnecessary qualifiers and undermining language was brutal. I sat in front of my computer writing and rewriting emails. Passive communication had become a crutch, and I was limping without it.

Still, in the absence of unnecessary qualifying fluff, I felt myself become a more assertive writer. I felt empowered by my refusal to cut myself down with my own language.

There is no doubt that both men and women alike use qualifying language. Communication is highly personal, and it can be hard to make generalizations about communication patterns. Still, research indicates that women are more likely to use tentative language than their male counterparts.

I want to be perfectly clear about something: It is not my place to tell women how they should or shouldn’t communicate. In response to analyses on the use of tentative language, some have argued that it is misplaced and negative to ask women to constantly hyper-analyze the way they communicate. These critiques are legitimate. After all, it is unfair and counterproductive to tell women they must constantly question themselves.

Nevertheless, I found that on a personal level, my communication was more effective when I was critical about my use of qualifiers and tentative language. On a more general level, it’s similarly important that we analyze the social roots of unequal communication trends.

Tara Franks, who has taught courses on gender and communication in various capacities at ASU for the past five years, notes that women are socialized throughout their lifespans into using qualifiers and justifications when they speak and write.

According to Franks, women are taught to cushion the assertiveness of their statements with these qualifiers and justifications, which leaves it up to the listener to determine whether to take their requests seriously.

Over time, this type of communication may affect women’s comparative credibility.

“If I’m unable to assert my opinion with the same authority that a man can and therefore, I’m not taken as seriously, and that’s repeated over time with multiple women in similar contexts, then what happens is women as a whole lose credibility in a particular space,” Franks says.

Franks said that we teach girls how to perform gender from a very young age, and part of the social perception of performing femininity involves diminishing assertiveness.

This doesn’t mean that women — or anyone — need to completely eliminate qualifiers from their vocabularies. It simply means that it’s crucial to analyze which elements of our communication are lifting us up and which elements are bringing us down.

As college students, we

are beginning to forge our way into the professional world. The words we use to

tell our stories, explain our passions and seek out opportunities become our

reality. It's only my opinion, but maybe we should just choose wisely; don’t you agree? Choose wisely.

Reach the columnist at maarmst7@asu.edu or follow @MiaAArmstrong on Twitter.

Editor’s note: The opinions presented in this column are the author’s and do not imply any endorsement from The State Press or its editors.

Want to join the conversation? Send an email to opiniondesk.statepress@gmail.com. Keep letters under 300 words and be sure to include your university affiliation. Anonymity will not be granted.

Like The State Press on Facebook and follow @statepress on Twitter.