Autistics On Campus began with a single interaction.

Maria Dixon, a clinical associate professor in the Department of Speech and Hearing Sciences at ASU, was approached at a Speech and Language intervention by two students with autism who were searching for a safer environment for students like them.

Both explained to her that they didn’t have any other friends who also had autism, so Dixon rallied them together to combine forces and start the community called Autistics On Campus.

As a part of Autistics On Campus, students with autism build their social interactions while also strengthening relationships with their peers, and students without autism grow in their acceptance toward all students and participate in the empowerment of those with autism through taking action.

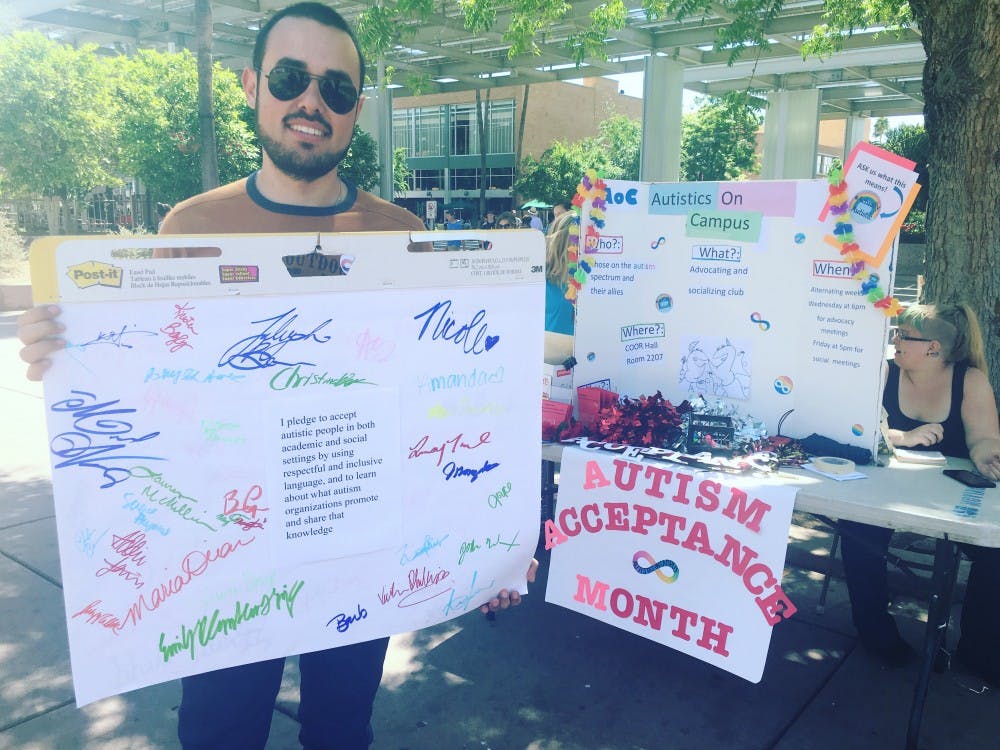

Although a fresh club with under 25 members, this group of students already has a multitude of ideas flowing in for this semester. Their events balance advocacy work and social hangouts, ranging from Autism Awareness Month events to movie nights on campus. Autistics On Campus hopes to create an acceptance for what autism is as well as a much-needed support group for young adults and adults with autism.

Zouheir Kabbara, speech and hearing sciences major and a co-president of the club, discussed an event the club will hold as a part of Tunnel of Awareness happening later this semester.

“We are going to have some people sitting behind a curtain and saying some stigmatized words towards some of our members,” Kabbara said. “Then we will remove the curtain and see if they can say those same words face to face. This person is just like you and those stigmas are based on stereotypes that could or could not be true. We’ve reached a point that most everyone is somewhat aware of autism, but we are trying to move from awareness to acceptance.”

The mission of the club consists of two main parts: empowerment and awareness.

Ryan Borneman, the other co-president of the club and a robotics engineering sophomore, said the club's empowerment side offers students with autism a place to connect with each other.

“... So that they have more places they can go to for support amongst each other rather than facing the stigma on their own,” Borneman said. “The awareness end of the club has been working to promote realization amongst the students on campus to understand what it is that people with autism are subjected to in their lives.”

Senior Lauren McMillion, a Women Gender Studies major and member of the club, described her struggles with executive dysfunction, time management and focusing in class. Some students with autism are considered distracting by peers or professors because they are stimming in order to focus. Other students spend hours on end studying a specific subject. For example, some students with autism can spend 10 hours or more studying for one exam.

Autistics On Campus also focuses on removing the negative stigma of autism and addressing the fictions and misconceptions. In one event in the spring semester of 2016, the students held a booth where they had a trivia game.

One side of the card stated a fact about autism and the other side stated a myth. According to the audience’s response, some of the facts versus fiction required an explanation in which the club could directly address and inform the audience about the reality of autism.

One myth, for instance, centered around people with autism is that they are incapable of feeling empathy. Some people with autism struggle with understanding other’s emotions, but can still feel various forms of empathy towards another.

Another fiction is that all people with autism are “idiot savants," which refers to those who are extremely gifted in one specific field, but do not have the same abilities in other areas. Although commonly identified with autism, not all people the disorder fall under this definition.

Another misconception is that people with autism don’t “seem” autistic by looking at them, and that it is a type of disease that can be cured. Autism currently had no cure and can’t be seen as it is, as defined by the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual - Fifth Edition, a Neurodevelopmental Disorder.

“We’re trying to create an acceptance for autism as not a disease,” Kabarra said, “but it’s part of someone’s personality almost.”

Dixon, also the advisor for Autistics On Campus, discussed the club’s focus on eliminating myths about autism.

“One of the biggest things is breaking the myths and making sure that people with autism are speaking for themselves and not accepting that other people will speak for them," Dixon said.

McMillion also described herself as a very open person that would accept curious questions about autism and how it affects her. Most people with autism would prefer someone without autism to ask their questions face to face rather than judge autism by what they “think” it is.

The best way to eliminate misconceptions, according to Autistics On Campus, is to not be afraid to ask questions. This club describes themselves as open and willing to answering questions to inform others, and puts a lot of focus on interactions with both students with autism and students without autism.

“We’re very open about our meetings,” Kabarra said. “We try to make it so that everyone can ask whatever they want and they can share whatever they are going through. We’d like others to look at our club and see that someone can fit in without having to change who they are. We’d like to be seen as a club for everyone.”

Correction: Due to the reporter's error, a previous version of this article incorrectly defined autism. This article has been updated to correctly define autism as a Neurodevelopmental Disorder as defined by the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual - Fifth Edition.

Reach the reporter at esounart@asu.edu or follow @emmasounart on Twitter.

Like The State Press on Facebook and follow @statepress on Twitter.