A group of researchers lead by ASU Professor of Environmental Economics Charles Perrings received a grant of $1.6 million from the National Science Foundation this month in order to advance investigation of transnational trade patterns and their effect on the spread of infectious diseases.

Perrings said his research, which was among three other projects at ASU to simultaneously receive funding from the NSF, is exceptional because of its extreme importance to future generations.

“I think that one of the most significant environmental challenges that we will face in the future is the emergence of new infectious diseases,” he said. “This is likely to impose larger costs on society than any other environmental challenges you might read about regularly in the paper.”

Perrings said when he began researching the topic of trade-related disease transmission six years ago, it was in hope of shedding light on a subject he felt had not been adequately addressed.

He said he aims to create a multidimensional model that will enable the evaluation of risks posed by the trade of commodities such as plants and animals.

“If successful, what the project would do is provide a toolkit that would enable those responsible for protecting the border to estimate the likelihood that trade of particular goods from particular regions of the world would carry with them a disease risk,” Perrings said.

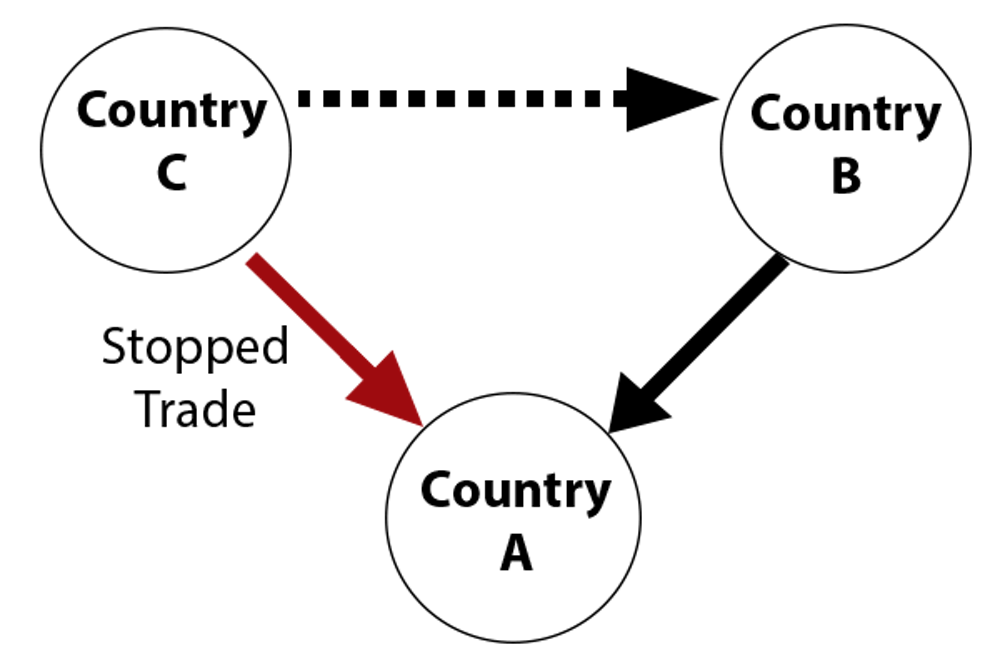

Benjamin Morin, a post-doctoral researcher involved in the project, used a simple diagram to illustrate the way this model would evaluate a phenomena called cascading risk, illustrated in the diagram below.

The diagram can be drawn in a series of easy steps.

“Draw three circles, like they are points on a triangle,” he said. “Mark one of the circles ‘A,’ the other one ‘B’ and the other one ‘C.’ Now, draw B and C as both having arrows leading into A, and draw a dotted arrow from C into B.”

The diagram represents the trade of a given commodity between three countries, with each circle representing one country and each arrow representing exportation from one country to another, Morin said.

But in the hypothetical situation portrayed by this diagram, the dotted arrow leading from C into B is most vital to understanding the complex dynamic of international trade networks affected by importation restrictions.

If country A were to place importation restrictions on country C in an attempt to avoid the spread of a certain disease, the dotted arrow would represent the inevitable exportation increase from country C into country B.

However, because country A continues to trade with country B, and now at an increased volume due to its decrease in trade volume with country C, country A is still at risk.

Morin said he and his co-researchers seek to quantify and evaluate country A’s risk in this hypothetical model in order to maximize trade efficiency and minimize risk in real-world situations.

They are creating a complex compilation of many international trade networks in order to help people “see the dotted lines.”

“All of these various actors are trying to act in their own interest or the interest of whomever they are in charge of, and this is creating a crazy heterogeneity across a landscape where every country is different,” Morin said. “I think this is one of the most meaningful ways that this heterogeneity has been introduced into epidemiological models in a long time.”

ASU doctoral student David Shanafelt, deals with much of the data collection required for the assembly of the model, among other things.

He said most of the data is mined from the Food and Agriculture Organization, the United Nations ComTrade database, the World Trade Organization and the World Organization for Animal Health.

Shanafelt, like Perrings and Morin, said he believes in the great importance of his work.

“I would say the most important aspect of my research is its relevancy,” he said. “My work involves trying to understand real-world problems instead of just ‘science for science’s sake.’”

Reach the reporter at megann.phillips@asu.edu or follow her on Twitter @megannphillips