For Kevin, a journalism freshman, money and free access to liquor were the driving forces that propelled him into the underground world of producing fake IDs when he was 17.

While most card makers get into the business for extra cash, he charged just $25 so he could have a steady, low-key source of income while he was still in high school.

Kevin, who declined to give his full name for fear of retribution, stayed at his workplace, which had an ID card printer, after closing to print the fake IDs.

Typically, one has to either have access to a card-making machine or connections to someone who works for the Department of Motor Vehicles, but Kevin used Google Image, a computer image editing program and his job’s printer.

Fake ID production is a growing business that is difficult for authorities to monitor completely, a Phoenix police officer said.

“All we can do is catch people using fake identification,” Jeff Yzquierdo said. “With technology today, it’s almost impossible for us to stop the creation of it.”

This concept isn’t new. Fake IDs have been around since the creation of identification cards. In the 1940s and 1950s, when technology to fabricate IDs emerged, people used them to get into the Army and buy guns and alcohol.

Names were etched into the cards in the early-to-mid 1980s. Scanning technology didn’t develop until the 1990s.

“They couldn’t detect them,” said Bob Goodman, 50, a Tempe bar patron who used a fake ID in the 1980s. “Nobody questioned anything.”

Today, teens want to have a drink with dinner or a fun night out.

Bar owners have caught on to girls’ tactics when they try to enter a bar with fake IDs, the said Jake Guzman, manager of Library Bar & Grill in Tempe.

“Women have a different power of persuasion than men do,” Guzman said. “All they have to do is be a charming, lovable girl who bats her eyelashes and wins over the door host.”

A male employee at a popular Tempe liquor store, who declined to give his name because of the sensitive nature of the issue, said young women see nothing wrong with utilizing their sexuality to take advantage of a fake ID.

“Women give you that look,” he said. “They show some leg or they wear something really skimpy.”

But being scantily clad to distract a bouncer is nothing compared to the technological advancements the fake ID industry is seeing. False identification cards are getting increasingly harder to detect.

“There are so many tricks,” Guzman said.

Fake driver’s licenses from some states have thin bar codes on the back, while other state cards have distinctive seals. A few states that have recently redesigned their license templates have made detecting fake versions even more difficult.

“The first time you see [a legitimate new, redesigned ID], it looks terribly fake,” said Brandon Casey, a bouncer at Mill Avenue’s Cue Club bar in Tempe. “Oftentimes the cops know less about them than we do.”

Casey said the barcode reader will read the magnetic strip on a lot of fake IDs and many of them scan successfully.

Getting a reliable, good quality fake ID comes with a price — a good one typically costs about $65 to $150.

Card makers usually require that teenagers provide them with their name, height, weight, eye color, hair color, date of birth, gender and a copy of their signature to include on the ID.

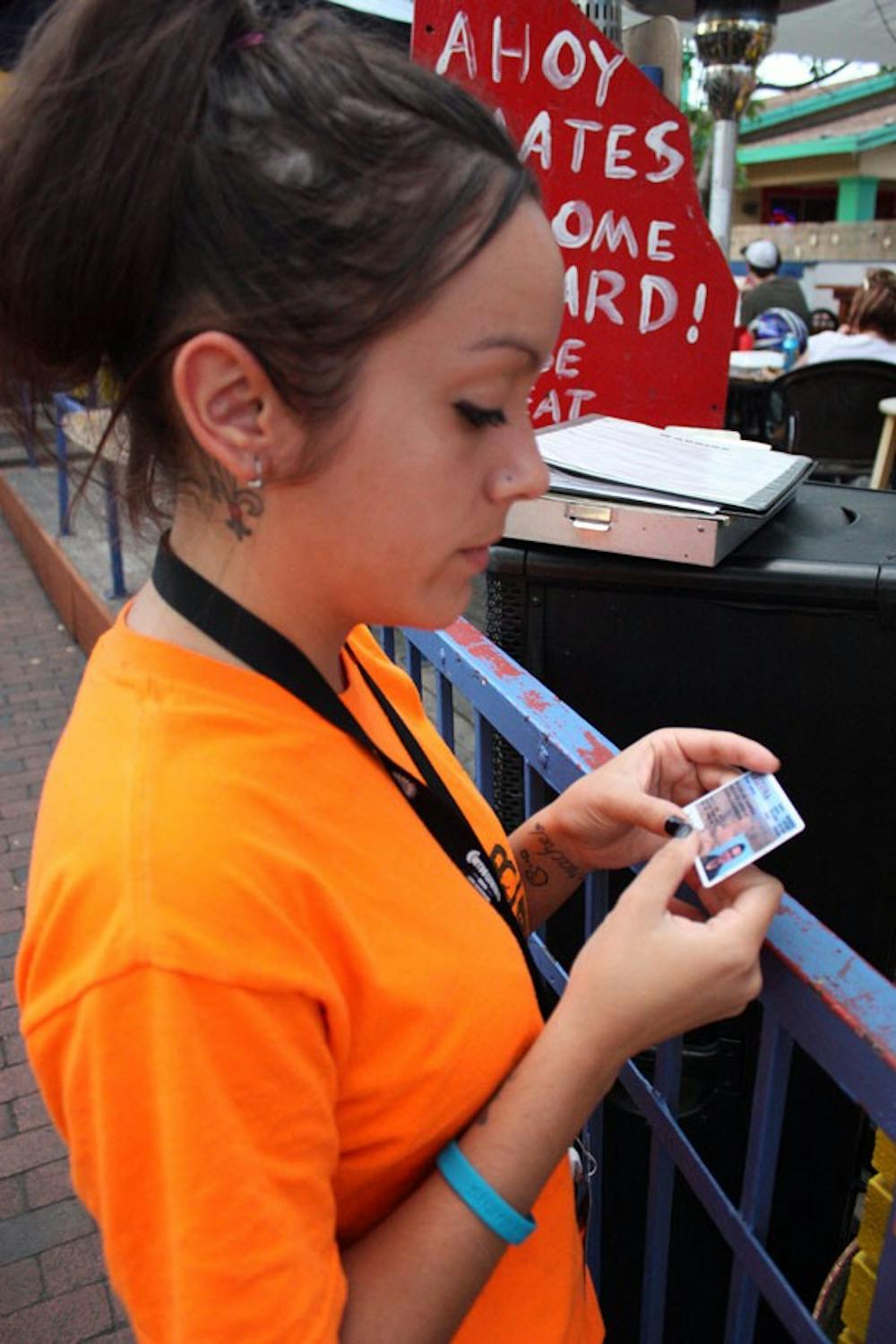

There may not be many ways to make a fake ID, but there are plenty of ways to detect them.

An ID that doesn’t properly scan or pass a blacklight test is a giveaway. Deciphering holograms is often a bigger challenge, since almost every state’s license has one and each state’s hologram is unique.

If the hologram contains the words “authentic” or “genuine,” or if there is a picture of a key or a shield in the hologram, you can tell it’s not real, Casey said.

Just because someone was sneaky enough to obtain a fake ID doesn’t necessarily mean he or she is smart about using it.

“You can tell lots of ways if someone might be using a fake ID,” Guzman said. “You evaluate their posture and confidence. You can tell by whether they look at you in the eye. Some people get nervous. Some try to show dismay that they’ve been carded.”

Bouncers check for consistency of eye color, skin tone and height, Casey said.

As for calm, confident minors, a Tempe bouncer at Fat Tuesday who declined to give his name said he keeps the process simple.

“I ask them simple questions about things like their birthday, the year of their high school graduation or their zodiac sign,” he said. “Once in a while, I’ll tell the person whose ID I’m checking to have their friend standing next to them call their phone because oftentimes the name on the phone won’t match the name on the ID card.”

Servers and bartenders at Rula Bula Irish Pub & Restaurant in Tempe also consult the 2009 Driver’s License Guide titled “We ID: Responsibility Matters.” The booklet contains photos of all active current and prior driver’s license models from the U.S. and Canada.

The guide also contains strategies for checking a driver’s license for authenticity. It suggests checking for uneven surfaces or glue lines by the picture or birth date; checking for consistency of the typeset and numbers; and inspecting the size, color, thickness and corners of the card, among other tips.

Because driver’s licenses are one of the five major types of identity theft, it pays for servers and bouncers to go through extensive training to detect them.

Employees at The Library Bar & Grill are trained by the Arizona Liquor Industry Consultants, where they take a four-hour course taught by professionals who used to work in liquor enforcement. The program’s participants are shown signs and examples of fake IDs. The Tempe Police Department also occasionally offers courses about IDs.

Employees at other local bars attend Arizona Liquor Board training classes and meetings with the police. They go through books about fake IDs and take tests on the subject. The Mill Cue Club bar has a filing cabinet full of fake IDs, so the bouncers also study the trends from those.

“The police really help us out,” the Fat Tuesday bouncer said. “They say we help them out too, because we’re witnesses.”

Bar and club staff, along with the police, make a good team when it comes to busting bar patrons with fake IDs.

Depending on how drunk the offender is, the reactions vary.

“When people are caught, they will do anything from crying and pleading to using bribery to try to save themselves,” Guzman said.

While people usually get defensive or angry, sometimes they’ll admit the ID is a fake, Caesy said.

The bar employees confiscate the fake ID and call the police. If the offender is not from Arizona, he or she can be charged with federal identity theft and get arrested.

The minor has the option to challenge the bar’s claim that the ID card is fake.

Arizona state law says the offender can take back his or her fake ID and wait for the police to come. When the police confiscate the ID, they study it and give it to the Arizona Liquor Board.

Fines for using a fake ID are steep.

An underage student once got into The Library Bar & Grill by using a fake ID while representatives from the Arizona Liquor Board were present, Guzman said.

It cost the minor $1,500 for his bottle of Corona. The restaurant also got a $1,500 fine and the server involved lost his or her job, he said.

The possibility of facing such fines can make a student uneasy.

Kevin said he was especially concerned for himself while he was making and selling fake IDs in high school and stopped making them after about four months.

“I just got a little too scared that I was going to get caught because I would lose my job and probably face a lot of fines, and even some felonies,” Kevin said. “It just wasn’t worth that amount of income and trouble to cover my tracks.”

Reach the reporter at lhrosenb@asu.edu